Oogy The Dog Only a Family Could Love (18 page)

Read Oogy The Dog Only a Family Could Love Online

Authors: Larry Levin

In warm weather when we go for a walk in the little nearby town of Narberth, strangers invariably approach us to meet Oogy. His appearance inspires a lot of questions. I generally try to avoid telling very young children what really happened to Oogy; I simply tell them that another dog attacked him. Because both humans and dogs had abused Oogy, strangers are unfailingly surprised that he is as gentle with animals and people as he is. When people first encounter Oogy, they invariably ask if he is safe. My stock response is, “Well, he has licked two people to death.…” Waitresses, waiters, and patrons at the outdoor cafés and people eating, drinking, or catching smokes outside of the bars and restaurants swarm all over Oogy. On weekend nights, several of the regulars in downtown Narberth carry treats to give to him. Oogy enjoys the attention that he gets. I am happy for him. It is some form of compensation. I often tell people we encounter on these strolls that we’re there because Oogy likes the nightlife. In a way, that’s true.

It is an altogether different experience when we go to a dog park and I let Oogy run free. This has served to both expand and strengthen our communicative abilities. For years, I was reluctant to let Oogy off his leash. The idea that he might run away and be lost forever reflected my anxieties: That which we love will disappear. But eventually, at Jennifer’s insistence, and knowing full well how much Oogy enjoyed socializing with other dogs, I overcame my hesitation. The end result was a mutual expression of confidence that we would always be there for each other.

The first dog park I took Oogy to was at a local nature conservancy, acres of hills and hiking trails with a creek at the bottom. Dogs were not officially allowed off leash, but people had been letting them run free there for years. The opportunity to run unhindered and exhaustively and to interact with other dogs was definitely therapeutic for Oogy. Each outing was like a playdate for a young child, stimulating and relaxing at the same time. He would come home from these outings and fall into a deep sleep, his social and physical needs sated.

It took Oogy several months before he would venture into the creek. Eventually, this became a key part of our visit. Oogy would walk in the water and drink as it meandered along. On those clear, hot days, his image reflected in the creek, the picture of Oogy and Oogy upside down in the water burned into my brain. Sometimes he would walk thirty or forty yards upstream as I followed on the footpath. I could hear him sloshing in the water but was unable to see him because of the thick bushes lining the bank, until he would eventually rejoin me on the trail. The act of separating and then reuniting had deeper implications.

To be sure, there were moments when Oogy disappeared, following some scent or movement, which proved to be just as scary for me as when I’d lost sight of Noah or Dan in a crowded store when they were young. When Oogy would disappear, I would stand and call his name, always worried that he would not be able to discern where the sound was coming from because of his missing ear. Then, when he returned, I would always tell him not to do that again because it scared me so much.

During one visit, a mother and her three young daughters were hanging out by the creek, and I heard Oogy barking as I approached. One of the little girls had waded across the creek and climbed onto a large rock on the other side. Oogy was barking at her. The mother just got the biggest kick out of that. She sensed that Oogy was concerned because of the separation. Her own dog was sprawled on the bank by the creek, paying absolutely no attention. As soon as the mother called her daughter back to the side of the creek where the rest of her family was, Oogy quieted down.

Another time, I walked along the path and listened as Oogy splashed upcreek until finally I heard him moving toward me through the brush. I did not recognize the dog that emerged. Whose dog was this? Where was Oogy? It took a moment to realize what had happened. Oogy was completely covered in putrid slate gray mud. He smelled like a fertilizer factory. Riding home with him next to me was really a testament to my love for him. It stunk like something had been dead in the van for days.

Ordinarily when Oogy gets some mud on him it dries quickly, and because his fur is so short, I can wipe him down with a warm towel as though he’s made of vinyl. But this was altogether different. When we arrived home, the boys had to hold on to Oogy while I hosed him down. Then I took warm, wet rags with dog shampoo and cleaned him further before rinsing him down a second time and then drying him with clean rags. That removed most of the sediment — and restored our relationship.

After the township’s board of commissioners imposed severe restrictions on the ability of dogs to roam the conservancy unleashed, I learned that a local cemetery allowed dogs to run free — the smell of dogs scared away gophers whose tunneling undermined the gravestones — and Oogy and I spent some time there. It was an altogether different kind of experience, without the sense of joyful abandon Oogy had experienced at the conservancy. The rolling hills of the cemetery had a dull uniformity to them. There was no creek. There was no one for him to romp with. The only times I saw other dogs there, they were too far in the distance for him to engage. We visited only four or five times, and none of the visits seemed even remotely satisfactory. It was obvious that Oogy sensed there was a difference. Walking among the graves, he never strayed. He never broke into a run. The lives of the dead, the frailty of being, a brief touch on the shoulder that we are wanted elsewhere — these were palpable. The proximity of the dead seemed a weight that neither of us could avoid.

Then, in an adjacent township, we found a legitimate dog park of some thirty acres, a place where dogs

are

permitted off leash. A small creek lies at the bottom of the park. Virtually any time of the day, dogs can be found running, fetching, rolling around, chasing each other in twos and in packs. We have been there when as many as thirty dogs were galloping across the plateau, walking, playing, dogs of every shape and size and color, breeds I had never heard of and could not have imagined. It’s like doggy heaven. The dog owners are a responsible group who watch out for one another’s pets. We know one another’s dogs by name and give them hugs and kisses as though they were our own; throw a ball or Frisbee for someone else’s dog; give water from the doggy water fountain to other people’s dogs. When another dog puts his muddy paws on my shirt so that he can give me a kiss, it is never a problem. After all, I tell his owner, we’re all here because we love dogs.

When Oogy plays with other dogs, they run and run in circles, wrestle, flop around. Watching Oogy barrel along makes me think of the films I have seen of old-time locomotives, the big black ones, pistoning forward. Oogy is nothing but power, all muscle and moving mass. He will run for the sheer joy of running. He has some regular friends, dogs he will invariably interact with, but on any given day there is no way to predict who will be there when we are. He has also earned the nickname “the sheriff.” When a couple of dogs start mixing it up, Oogy will invariably run to the altercation and check it out, and more than once he has started backing off the aggressor dog with barks and shoves. Then, once peace has been restored, he will return to what he had been doing before.

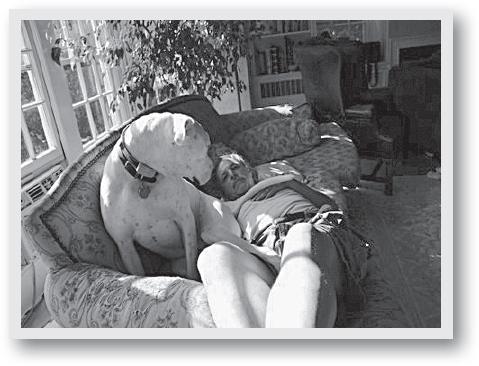

Allowing Oogy the autonomy to wander off leash has proved to be beneficial to his sense of himself as well as to our relationship. He wanders, explores, and sniffs at things I cannot see. He will dawdle along, sheer strength and ferocity gone gentle, smelling flowers, meandering without a care under the canopy of trees and amid the tang of honeysuckle. At the park, he is very independent, while at home, he seems always to need to be around one of us.

Oogy has appreciated the confidence shown in him to be off leash and on his own. He revels in the opportunity to interact with other dogs. By letting Oogy run free and mingle, and allowing him to wander in the stillness of the woods, where the only sounds are the creek and the occasional bird, the thrumming of a frog like some bass Jew’s harp, the whine of insects, we have been able to step out of and beyond the routine of our lives and in so doing have grown closer together. The trust I have placed in him and the independence he experiences have confirmed that, as with so many things, I was very, very wrong: He will never leave me.

I have told Jennifer and the boys that after I die, this is where I want my memorial service held and my ashes scattered. It is a scene of great peacefulness, happiness, and love. I have asked that Oogy’s ashes accompany mine. Just the other day, when I told the boys, Noah asked if instead I wanted to be buried next to our old pets just to the left of the front door. “I don’t know if we’ll own our house then,” I said. “And anyway,” I added, “with Oogy, it’s different. He and I are connected on a different plane.”

They said that they understood.

t

he boys’ impending departure for college will bring both big and small changes. The fundamentals of our lives will have been altered. My daily schedule now that I will not have to awaken and make the boys breakfast, the grocery list, the laundry demands, what Jennifer and I will do with the time we are not spending at games and wrestling matches each week and on weekends, all represent change. Everything will become different, some in ways I can envision and others in ways that will surprise and, no doubt, tug at me.

Although both Dan and Noah were accepted into several of the same colleges, in the end they made choices that took them thousands of miles apart. Noah received an academic scholarship to a local, highly rated college, which also has a strong lacrosse program; he will play on the team, and major in business and minor in coaching so he can coach lacrosse upon graduation. Dan decided that he wanted a different cultural experience than offered by the East Coast, and went out west. His sense of challenge and adventure has led him to declare a major in criminal justice.

How the boys will deal with the separation — from Oogy and from each other — remains to be seen.

As for me, since I will have a lot more free time than I have had in the past eighteen years (none, for the most part), I recently began the process to have Oogy certified so that he can become a therapy dog. My hope is that he will be licensed as a companion dog for hospitalized children and wounded veterans. Beyond the ordinary benefits that companion dogs provide, it makes sense to me that young people in the midst of personal struggle — battling pain, depression, and anxiety and daunted by the future before them, what they will look like, how people will react to what they look like — will be encouraged by and take some inspiration from Oogy. They will see in front of them living proof that the most agonizing and horrific events can be overcome without any lasting damage to the spirit, without harm to the ability to give and receive love. I believe that Oogy will be able to help those in need to understand that scarring, disfigurement, and trauma, whether physical or emotional, do not have to define who they are. That what is on the inside counts more than what is on the outside. That no matter what has been inflicted upon them, love and dignity are attainable.

I was talking to a nurse at the dog park and allowed that I was not sure

I

was ready for these encounters. She told me that I would quickly adjust. I have my doubts, but it made me feel better to defer to her expertise.

Before an animal receives certification as a therapy pet, he (or she) must undergo hours of obedience training, following which the dog is tested by the sponsoring organization (and in some cases the particular facility itself has more stringent standards) to prove that the candidate is calm and under his or her master’s control. There are simple sit and stay tests, tests for walking on command, and one that I anticipate will be hardest for Oogy: sitting while I walk away and not moving toward me until he hears the appropriate verbal command. Some of the tests are administered while rolling carts rattle, pans are dropped, glass breaks, or other dogs pass by. Ardmore recommended a man with decades of experience who is also the author of several well-received books on training dogs. He came to the house and we spent a number of hours together, much of it just talking about people-dog relationships.

He conceded that he had not anticipated the level of disfigurement on Oogy’s face. “I knew that his ear was missing,” he said, “but I never would have guessed that the damage to his facial structure was so extensive.”

We started the training with some game playing using a tennis ball on a knotted piece of rope. The trainer had me throw the ball and give Oogy a treat when he brought it back and gave it to me. The next two times I tried this on my own, Oogy quickly lost interest in anything but the treats in my shirt pocket and would simply stand there and stare at them. The trainer and I have not had a second session yet.

Before he left, though, the trainer said something that made

me

feel rewarded. He said that Oogy and I have a relationship based on mutual love and respect, a confidence that each will be there for the other. “You’re one hundred percent bonded with your dog,” he said. “There’s no distinction between this dog and the rest of your life. You’re in a place that we try to take dog owners to, but very few of them ever get to.”