Oogy The Dog Only a Family Could Love (19 page)

Read Oogy The Dog Only a Family Could Love Online

Authors: Larry Levin

I have never felt that my family did anything special or unusual in adopting Oogy. We just happened to be there when the opportunity presented itself. We didn’t do it so we could feel good about ourselves for having done it — although we have felt good about ourselves for being able to help him. We did it without thinking (well, Jennifer did the thinking for us). We met and fell completely and instantaneously in love with a dog who had had unimaginable horror inflicted upon him. We did it for the dog, a dog who was obviously special. What he had endured seemed to have put him on a different plane. And in our naïveté, we did not know that we might not be able to do what we did; that the odds were very much against allowing us to take an abused fighting dog and help him unlock the love in his heart for all living creatures.

I have heard it said that you can tell a lot about a person from his or her pet. I do not know what Oogy ends up saying about us. We do not operate on some elevated level of kindness. It is not uncommon to encounter dogs that have been adopted after they have been injured. I know several three-legged dogs from the dog parks: One was shot in a hunting accident; a car hit another; the third, a fighting dog, was found on the streets of Philadelphia with half his left rear leg missing and the bone jutting out. The owner of another dog who lost some facial structure to cancer had plastic surgery performed on it to restore his face and ability to eat properly. I know a Jack Russell terrier whose hind legs do not work: His owners place him in a little two-wheeled cart so that he can get around and call him “the million-dollar dog.” I know a family who found a stray who had cigarette burns all over her body and took her in; another family adopted a dog from a breeder who planned on killing him simply because he was a runt. A woman I recently met adopts strays with major medical problems, takes out a mortgage on her house to pay for treatment, and, when she has paid off the mortgage, takes out another one for different animals.

And these are only the very small number of people whom I have come to know within my own community. They speak for a collective experience of vast proportions. At the same time, I have come to understand that what Oogy went through — the unspeakable torture he was subjected to as part of some barbaric cultural exercise — and the odds that he had to overcome to have survived at all make his story, and therefore our experience, somewhat unique. He is not the product of accidental injury, but a living symbol of an epidemic that kills thousands of dogs each year. And if there is a reason this story has a happy ending, a large part of that is because every day I think about how it began.

I also think that because they are adopted, the boys relate to Oogy on another level as well. On their eighteenth birthday, I asked Noah and Dan several more of those questions I had no way of knowing the answer to. I wondered if the fact that they are adopted had influenced their lives, and if so, how. Did they feel rescued or saved in the manner in which Oogy had been rescued? Did they think that the fact they were adopted had influenced the way they related to Oogy?

I told them I was not expecting immediate answers, to take as much time as they needed, and that whatever they wanted to say would be fine. I was not looking for anything in particular. I just wanted to know. I actually wasn’t sure they would be able to answer the questions — I know I couldn’t have done it when I was their age.

But they could.

Dan said that he does not sit around and think about the fact that he is adopted. “I’m aware of it, of course, but I don’t dwell on it,” he said. He considers it to be a component of his identity, “the same as the fact that I’m a Caucasian male. I don’t sit around and think about how my life would be different if I weren’t a Caucasian male. I don’t think about what effect it’s had on my life, either. It’s who I am.” He told me that he never thinks in terms of Jennifer and me not being his parents. “I mean, for the last eighteen years, except for three days, which I have no memory of, you’ve been my mom and dad.”

Dan understands that the fact that his birth parents placed him for adoption does not mean they rejected him. He appreciates that it represents an incomparable sacrifice, an act of love not only for his benefit, but also for the benefit of total strangers. At the same time, Dan does feel that he was “in a way” saved. Not in the sense that he was in any kind of danger, the way Oogy had been, but because he has never wanted for anything and has been provided with a loving, supportive home environment and significant developmental advantages, both intellectually and athletically, that he feels certain would otherwise have been unavailable to him. Dan also thinks that this sense of feeling lucky and advantaged is related to why he is so crazed about saving animals. “I can’t know how I’d have related to Oogy were I not adopted,” Dan explains. “But I have to think it has affected how I feel about him. We share the same experience. We both have better lives for it. I want to help him and love him the way I have been loved and guided.”

In the end, it is not the fact that he is adopted that has affected Noah, it is the act of adoption itself. “I mean,” he said, “for all the things that had to have happened to get me here, to have in fact happened, I find that pretty amazing.”

Just like Dan, Noah has a sincere sense of appreciation for the quality of life he has enjoyed. The friendships he has been able to develop, the academic opportunities he has been offered, the fact that we were always able to somehow pay for lacrosse camps and basketball camps and overnight camps and lacrosse clubs and individual coaching, the occasional vacations, even a trip to Paris we took when they turned thirteen — all represent advantages and experiences that he is the better for and which he feels in all likelihood he would otherwise never have had. Because of that, he thinks he is more thankful for what he has been offered than someone who is not adopted but has had similar opportunities.

Noah agrees with Dan that he has never felt that he was rescued or saved. “I think things would have turned out a lot differently, but, really, how can I speculate about how things would have turned out? I’m very happy with what happened to my life. That’s all that matters. And I definitely think the fact that Danny and I are adopted has affected my relationship with Oogy. We all arrived here through circumstance. Maybe it’s fate. Danny and I weren’t born here. You didn’t even know we existed till Golden Cradle called you. Well, that’s what happened with Oogy. We didn’t know he existed, but he was alive before he ever became part of our family. What would have happened to us if you had not adopted us? I mean, me and Danny and Oogy. We all come from some place else and now we’re here and who knows how that happened?” Noah grinned. “Oogy’s my brother,” he said.

When he told me this, Noah knew nothing of my belief in the role fate had played in bringing Oogy to us. This is but one of the common elements that tie the boys and Oogy together. There are remarkable similarities in their stories. Perhaps this is why Oogy’s integration into our lives has been seamless and complete.

The magnificent and wholly unanticipated rewards that have come our way from Oogy make it difficult for me to believe that anyone could have made a different decision than we did. On many occasions, I have somewhat glibly told people that I did not rescue Oogy, the police did. I simply brought him home. The truth is, I tell them, that Oogy rescued me.

Finally, I started to think about the implications of that statement.

Even though I was not conscious of it — and in fact, mirroring what my parents had taught me, pushed it down to the bottom of my being so that it seemed as if it had never happened — my sister’s death and my parents’ reaction to it understandably, inevitably, and irrevocably reverberated down the passage of the rest of my life.

Perhaps as a child, unable to understand the dynamics involved, I wished I had died instead of my sister so as to spare my parents their grief. I know that until I became a father and saw the value of life, I used to think that the moments in which I could feel most alive and could most appreciate the experience of being alive were in the proximity of danger and death. No doubt as a result, I spent several years with the U.S.D.A. Forest Service on an interregional Hotshot crew fighting forest fires. Hotshot crews perform the initial attack on large fires, flying and busing from one to another for weeks at a time. My friends on the crew and I treated it as a unique experience, full of laughs, but really we were willfully ignorant of the dangers we encountered on a regular basis. That did not mean, of course, that they were not there. We simply disregarded them: falling timber, crashing limbs, hurtling boulders, poisonous snakes, tons of slurry dropped from planes that could crush you and explode the fire around you, helicopters that could fall from the sky at any moment, fire waiting just on the other side of everything we did.

But I think that all of this may also explain my immediate attraction to Oogy. I saw

myself

in him. I saw the burning of the metaphoric fire that almost consumed him resonate in the way that fire had made me feel alive. I saw how death had had its way with both of us. Proximity to death had shaped us. For me, raising the boys had carried an element of self-doubt, which is why I have always told people that I think the boys turned out as well as they did despite me, not because of me. But with Oogy, with this dog, there was never a moment’s doubt that all the returns would be positive. And I raised him as I tried to raise the boys, as I wish I had been raised: a full-contact relationship free of ambiguity as to their central place of importance to the family.

And Oogy had come back from the dead to be with me. Neither my sister nor my parents had been able to accomplish that. I could keep him alive. I knew how to make him happy. I had been unable to do that before. I could not keep my sister alive or bring joy and a sense of fulfillment to my parents.

But I could do it for Oogy.

W

e wanted to get the boys something unique for high school graduation gifts and were lucky enough to find hand-carved sculptures that the artist calls Journey Boats. The Journey Boats are symbols intended to represent exploration and passage.

The boats themselves are the long, flat-bottomed type the pharaohs used for hunting the marshes, an experience they considered to be sacred in nature. On the prow of each boat, a protective eye guides.

Based on photographs we supplied to the artist, she carved likenesses of both boys and Oogy in each of the boats. In Noah’s boat, he wears a red shirt; Dan, wearing a blue shirt, sits behind him with his right hand on Noah’s shoulder. These positions are reversed in Dan’s boat. They are looking confidently ahead, ready for whatever it is they are going to encounter. They have always covered each other’s back, so their positioning and the supportive hands on each other’s shoulder represents that. While they are about to embark on separate explorations, their steadfastness and physical contact have an additional meaning: We know that because of the special bonds they have with each other, they will make the journeys loving and supporting each other along the way.

While the boats have similarities, as do the boys’ lives, there are also differences that distinguish them from each other. The boats are different colors. The prow of one is adorned with a dove, which is both the bird that Noah let out of the Ark to find land and a symbol of peace, representing our hope that there will be peace for the boys throughout their respective journeys. On the prow of the other is a bee, the symbol of hard work and achievement; they have both been long aware of the necessary connection between the two.

An observation by Graham Greene is carved on the bottom of each boat: “There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.”

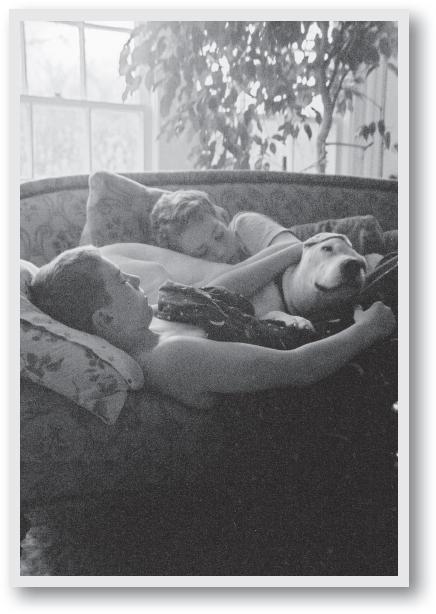

Oogy has been and always will be an important and integral part of their lives, and thus their journeys, and they have always been appreciative of the unique and exceptional experience of having him in their lives. The love they have shared has not only been its own reward, Oogy’s love for the boys has always been as meaningful to them as their love for him has been important to him. As a result, Oogy sits in each boy’s boat; he will be with them forever. He sits in front of them, his right ear alert, staring ahead just as they do because, without fear, he is watching out for them, just as he always has and just as he always will.

Behind him, the boys are also watching over him. Just as they always have. Just as they always will.

Jennifer and I made a conscious decision not to include ourselves in the boats. The boats are intended to symbolize the boys’ explorations that are starting now that they have graduated high school. Everything that has happened before has simply led them to this point. Jennifer and I have brought them here and pushed them into the current that will take them into the rest of their lives. When Noah and Dan turn around, they will see us standing on the shore, growing smaller and smaller, waving and waving good-bye.