Oogy The Dog Only a Family Could Love (11 page)

Read Oogy The Dog Only a Family Could Love Online

Authors: Larry Levin

I reached over and switched off the lamp. The picture of the three of them sleeping together that first night, illuminated by light outside the window, where a strong wind rustled the trees, imprinted itself indelibly in my memory. Two young boys, backs to each other, curling hair against the pillows, and a little, white one-eared dog between them. Then, exhausted by the whirlwind events of the day, the book on my lap, I drifted off, and the four of us slept, me at a right angle to the three of them, until Jennifer came home and woke me.

“Hello, Oogy,” she whispered sweetly. “Welcome to our house.”

His tail thumped the bed, but otherwise he did not move. He was surrounded by love for the first time in his life, and he was not about to give that up for anything.

Years later, Noah told me that he remembered lying on the bed with Oogy that first night, and he thought, I hope my parents felt as good about us the day they brought us home as I feel about this dog right now. Oogy’s need for contact, the way he leapt onto the bed with them as though he were perfectly entitled to do so and went to sleep between them, allowed Dan to immediately appreciate that there was something special in the nature of the dog.

The fact that a brutalized, mutilated pup had so immediately and so completely reposed his trust in us made all of us feel that we had been rewarded.

He was one of us.

t

he next morning, the second day of Oogy in our lives, when the alarm went off and I managed to wrestle myself out of bed, I did not make it three feet before I heard a thump from Noah’s room, the clacking of toenails on the hardwood floor, and the jingling of the tags on Oogy’s collar as he ran to greet me. I dropped to one knee and said, “Good morning, pal. Good morning, Oogy. Did you sleep okay?” I gave him a vigorous rubdown, slapped him gently on the flanks. “And what would you like for breakfast this morning?” I asked him. “Pancakes okay with you?”

He followed me into the bathroom, standing there while I washed my face and brushed my teeth. He followed me downstairs into the kitchen, wagging his tail the entire time as though it were motorized. I mixed up his food, and snuffling and grunting, he bent to it. After starting the coffee, I clipped the leash on him and we headed outside, where a bitter wind was blowing. His fur was so short that I wondered if I should buy him a protective covering of some sort.

When we went back inside and I planted myself at the foot of the stairs to call upstairs to wake everyone, Oogy was by my side. In the kitchen, while I made breakfast for the boys, Oogy lay on the floor watching me. He sat with the boys while they ate, wandered upstairs with them while they dressed, sat with them while they watched TV, joined us in the kitchen when they left for school. From the moment he had crossed the doorsill, he had been inseparable from us.

And every weekday morning after Jennifer and the boys had left, and after we’d had our couch time and I was ready to leave the house, I would have to drag Oogy to the crate by his collar and push his backside into it, and he would bark and bark in protest. I wasn’t insensitive to this, but I thought that since crate-trained dogs loved their crates, Oogy was simply complaining that we were leaving him alone and that once he was alone, he would surrender to the safety the crate represented. It never occurred to me that something else might be going on.

Apart from his resistance to the crate, it was remarkable how thoroughly Oogy enjoyed whatever it was he encountered. He was so happy to be where he was that he almost seemed to be carrying an electric charge. When friends came to visit, as soon as he heard a vehicle in the driveway, Oogy would leap off the couch or whatever chair he was on and dash into the hall. For a moment or two his churning legs would search for a foothold on the throw rug there before he would go tearing out the back door. He would greet our visitors by placing both paws on whichever side of the car he could reach first, standing on his hind legs to peer in. As a young dog, he was also fond of standing up on his back legs and placing his front paws on the chest or shoulders of people he was meeting for the first time. This necessitated quite a number of red alerts around the elderly, including Noah and Dan’s great-aunts and great-uncles. One afternoon, Jennifer was playing with Oogy in the yard when he started running in circles. I later learned this was an expression of sheer happiness. This time, though, after one of his circles had been completed, Oogy ran directly into Jennifer, knocking her down. Her right knee was swollen for days. We had no way of knowing at the time that the act of hurling himself against her was a reflection of what he had been bred to do.

Years before the boys were born, my brother had given me a cartoon he’d clipped out of a magazine in which a stern-faced judge in a black robe is looking down at a little doggy and, gavel raised, declares: “Not guilty, because puppies do these things.” Diane had cautioned Jennifer that because Oogy was young and obviously so high-energy, his behavior might not always be what she would like it to be. She also told us that pups calm down after one and a half to two years. “It’s almost like someone has thrown a switch,” she said. While my overall approach was that nothing he did would shock or dismay me, it is fair to say that none of us could have possibly imagined the extent of the havoc he was able to wreak in his puppy days.

In his first six months with us, in addition to chewing up the futon couch, Oogy gnawed the middle out of the seat cushions of the two camelback sofas in the living room. He bit the eraser off any pencil he could find and would climb onto tables and desks to get at them. The decapitated pencils were left where they had fallen. He ate a pair of my glasses and a pair of my mother-in-law’s glasses. He chewed apart a wooden drawer in the kitchen. He ruined videotapes, countless CDs and CD cases, pens, crayons, and markers. He broke through every screen on every door in the house and scratched the paint off doors when he wanted to get out. He ate the antennae off every landline telephone in the house and then ate them off the replacements. He ate boxes of crackers, cookies (packaged and homemade, it made no difference), and loaves of bread.

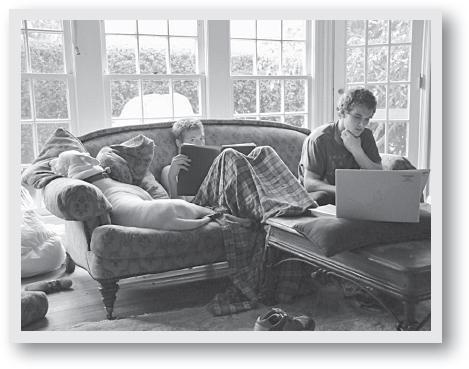

A number of Noah’s and Dan’s friends were afraid of Oogy’s rapidly expanding size and strength; others were annoyed and even alarmed by the manic energy he exuded and that demanded constant attention. A few, or their parents, distrusted Oogy because of all the bad press pit bulls get. As a result, the number of the boys’ friends who came to visit dwindled. When the visitor was someone Oogy did not know, he would get very excited. His favorite greeting activity was to bite guests at their ankles. As he became familiar with the visitor, his playfulness, or his sense of wanting to be the center of attention, would abate. Oogy quickly became as comfortable around the boys’ friends as he was with the boys themselves. Those of their friends who continued to come by — all boys with dogs in their own households, as it turned out — quickly found themselves the object of Oogy’s affection. After all, he could love Noah and Dan anytime and the rest of the time. It was not an unusual occurrence to come home and find Oogy draped over the lap of one of their friends while the boys sat on the floor playing a video game, or sleeping next to a boy sitting on one of the couches.

When Oogy came to live with us, for Noah and Dan it was in many ways like gaining a little brother. It soon became apparent to all of us that Oogy did not know he was not human; his bond with the boys made itself evident in incident after incident. Whatever the boys did, he insisted on being included; wherever they went, he wanted to go. When the boys ate, Oogy sat next to them watching them, barking at them for food as though they did not understand that he was right there and deserved some of whatever they were having. When the boys wrestled or had a pillow fight, Oogy threw himself into the mix. If they fought with each other, he would begin barking and jumping on them. When they played table tennis, he dashed back and forth with the ball, barking furiously, and when the ball hit the ground, there would be a mad, comic rush to see who got to it first; if it was Oogy, he would scoop it up, often without crushing it, just holding it in his mouth. If they were throwing around a lacrosse ball outside, he would race madly back and forth between them, following the flight of the ball and nipping at their ankles. When the three of us would throw a ball around, I was the only one whose ankles went unbitten. “That’s because you’re the alpha male,” Noah suggested. If they went outside to have a catch or play basketball or football with friends, Oogy would demand to participate. If the boys left Oogy inside to go play football or to have a catch, he barked and whined incessantly and clawed at the door, alternately pacing back and forth, barking and yelping with frustration. Eventually, we realized that the only way the boys could play outside was for me to take Oogy off the property for a ride or a walk. We learned that if Oogy saw them leave the house before he did, he would try to follow them and would be uncooperative about getting into the car. As a result, when they wanted to do something outside, I would ask how much time they needed and would head out with Oogy before the boys left the house.

Once the electronic fence had been installed, when the boys left the property Oogy would run their scent to the edge of the yard as soon as I let him outside and sit staring up the street after them. He would sit there as long as I let him.

Oogy simply had no idea that he was a being separate and apart from the boys. In his view, he shared his life with them, and therefore there was never a doubt that they shared their lives with him. Around our house, he became known as “the third twin.” As with any little brother, Oogy’s insistence on being with Noah and Dan and doing whatever it was they were doing could be annoying for them. I repeatedly had to explain to the boys that when they were home alone after school or home with friends, one of them had to pay attention to Oogy, because if they ignored him, he would most likely do something destructive.

“He’s like a little kid,” I told them.

“Yeah,” observed Dan, “but one who’ll never grow up.”

One morning shortly after Oogy came to live with us, and before we had the electric fence, after the boys headed up the street to middle school, I went out the door with Oogy to take him for a walk. He immediately slipped the collar and took off after them, following their scent. I ran along after him, though in a moment he was gone from view. When I found Oogy on the playground, he was surrounded by a dozen kids, including the boys, and a teacher’s aide. Oogy was sitting in front of the group. Several of the children were petting him calmly. I was somewhat embarrassed, but everyone else seemed to think that it was really cute how he had followed the boys up there. And I must admit, he had thoroughly surprised even me. I had run after him expecting the worst, some imagined manifestation of pit bull ferocity preprogrammed into my brain, when all there was to it was pure adoration of the boys and a desire to be with them.

From the outset, I was reluctant to discipline Oogy, as I was with the boys, by invoking anger, deprivation, or fear. Not only did I consider these techniques to be counterproductive, but I was worried that they might alienate him from us. And I especially didn’t want to use them with Oogy. He had already spent more than enough time afraid. I didn’t have it in me to do that to him again.

If there was a downside to this, I never saw it, but there were visitors to our house who found the extent of license Oogy enjoyed somewhat disconcerting. He sat and slept wherever he wanted, and on more than one occasion, he climbed onto the dinner table while we were eating. This happened one memorable time when college friends were over. They looked at Oogy as if he were on fire, and then back and forth at one another, and though they didn’t say anything about it, I never heard from them again.

As he grew out of puppyhood, Oogy continued to have an appetite for mass destruction that would not abate for another year and a half. One morning when the boys were in seventh grade, he chewed a hole in Noah’s math homework. Jennifer wrote a note to the teacher that began, “You’re not going to believe this, but…” He tore apart insulated galoshes, flip-flops, scarves, sneakers, shoes, plastic fruit, and the head of one of Noah’s lacrosse sticks. He chewed up hard rubber dustpans, fly swatters, and brushes. He ate books, barrettes, and toothbrushes, shredded newspapers, ripped apart magazines, and tore chunks out of books. There is a sizable glop of glue on the rug in the dining room because Oogy chewed the top off a bottle of the stuff, and there appears to be no solvent to dissolve it that won’t also take the rug with it. I have no idea how he avoided doing major damage to himself with that one. He ripped open packages, tore apart mail, ate a whole tray of brownies, chewed into countless boxes of energy bars, and raided the trash relentlessly. He ate plastic figures of the Lone Ranger and Tonto that Dan gave Jennifer one year for her birthday.