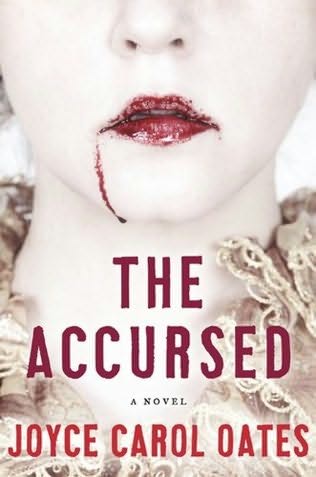

The Accursed

for my husband and first reader, Charlie Gross;

and for my dear friends Elaine Pagels and James Cone

From an obscure little village we have become the capital of America.

—A

SHBEL

G

REEN

,

SPEAKING OF

P

RINCETON

, N

EW

J

ERSEY, 1783

All diseases of Christians are to be ascribed to demons.

—S

T.

A

UGUSTINE

CONTENTS

Postscript: “Ash Wednesday Eve, 1905”

Angel Trumpet; Or, “Mr. Mayte of Virginia”

Author’s Note: Princeton Snobbery

Author’s Note: The Historian’s Confession

Postscript: The Historian’s Dilemma

“God’s Creation as Viewed from the Evolutionary Hypothesis”

Part Three

- “T

HE

B

RAIN

, W

ITHIN

I

TS

G

ROOVE

. . .”

“A Narrow Fellow in the Grass . . .”

Dr. Schuyler Skaats Wheeler’s Novelty Machine

Postscript: On the Matter of the “Unspeakable” at Princeton

“Sole Living Heir of Nothingness”

The Temptation of Woodrow Wilson

Postscript: “The Second Battle of Princeton”

Dr. De Sweinitz’s Prescription

“Revolution Is the Hour of Laughter”

An event enters “history” when it is recorded. But there may be multiple, and competing, histories; as there are multiple, and competing, eyewitness accounts.

In this chronicle of the mysterious, seemingly linked events occurring in, and in the vicinity of, Princeton, New Jersey, in the approximate years 1900–1910, “histories” have been condensed to a single “history” as a decade in time has been condensed, for purposes of aesthetic unity, to a period of approximately fourteen months in 1905–1906.

I know that a historian should be “objective”—but I am so passionately involved in this chronicle, and so eager to expose to a new century of readers some of the revelations regarding a tragic sequence of events occurring in the early years of the twentieth century in central New Jersey, it is very difficult for me to retain a calm, let alone a scholarly, tone. I have long been dismayed by the shoddy histories that have been written about this era in Princeton—for instance, Q. T. Hollinger’s

The Unsolved Enigma of the

Crosswicks Curse: A Fresh Inquiry

(1949), a compendium of truths, half-truths, and outright falsehoods published by a local amateur historian in an effort to correct the most obvious errors of previous historians (Tite, Birdseye, Worthing, and Croft-Crooke) and the one-time best seller

The Vampire

Murders of Old Princeton

(1938) by an “anonymous” author (believed to be a resident of the West End of Princeton), a notorious exploitive effort that dwells upon the superficial “sensational” aspects of the Curse, at the expense of the more subtle and less evident—i.e., the psychological, moral, and spiritual.

I am embarrassed to state here, so bluntly, at the very start of my chronicle, my particular qualifications for taking on this challenging project. So I will mention only that, like several key individuals in this chronicle, I am a graduate of Princeton University (Class of 1927). I have long been a native Princetonian, born in February 1906, and baptized in the First Presbyterian Church of Princeton; I am descended from two of the oldest Princeton families, the Strachans and the van Dycks; my family residence was that austere old French Normandy stone mansion at 87 Hodge Road, now owned by strangers with a name ending in –

stein

who, it is said, have barbarously “gutted” the interior of the house and “renovated” it in a “more modern” style. (I apologize for this intercalation! It is not so much an emotional as it is an aesthetic and moral outburst I promise will not happen again.) Thus, though a very young child in the aftermath of the “accursed” era, I passed my adolescence in Princeton at a time when the tragic mysteries were often talked-of, in wonderment and dread; and when the forced resignation of Woodrow Wilson from the presidency of Princeton University, in 1910, was still a matter of both regret and malicious mirth in the community.

Through these connections, and others, I have been privy to many materials unavailable to other historians, like the shocking, secret coded journal of the invalid Mrs. Adelaide McLean Burr, and the intimate (and also rather shocking) personal letters of Woodrow Wilson to his beloved wife Ellen, as well as the hallucinatory ravings of the “accursed” grandchildren of Winslow Slade. (Todd Slade was an older classmate of mine at the Princeton Academy, whom I knew only at a distance.) Also, I have had access to many other personal documents—letters, diaries, journals—never available to outsiders. In addition, I have had the privilege of consulting the Manuscripts and Special Collections of Firestone Library at Princeton University. (Though I can’t boast of having waded through the legendary

five tons

of research materials like Woodrow Wilson’s early biographer Ray Stannard Baker, I am sure that I’ve closely perused at least a full

ton.

) I hope it doesn’t sound boastful to claim that of all persons living—now—no one is possessed of as much information as I am concerning the private, as well as the public, nature of the Curse.

The reader, most likely a child of this century, is to be cautioned against judging too harshly these persons of a bygone era. It is naïve to imagine that, in their place, we might have better resisted the incursions of the Curse; or might have better withstood the temptation to despair. It is not difficult for us, living seven decades after the Curse, or, as it was sometimes called, the Horror, had run its course, to recognize a pattern as it emerged; but imagine the confusion, alarm, and panic suffered by the innocent, during those fourteen months of ever-increasing and totally mysterious disaster! No more than the first victims of a terrible plague can know what fate is befalling them, its depth and breadth and

impersonality,

could the majority of the victims of the Curse comprehend their situation—to see that, beneath the numerous evils unleashed upon them in these ironically idyllic settings, a single Evil lay.

For, consider: might mere pawns in a game of chess conceive of the fact that they are playing-pieces, and not in control of their fate; what would give them the power to lift themselves above the playing board, to a height at which the design of the game becomes clear? I’m afraid that this is not very likely, for them as for us: we cannot know if we act or are acted upon; whether we are playing pieces in the game, or are the very game ourselves.

M. W. van Dyck II

Eaglestone Manor

Princeton, New Jersey

24 June 1984

I

t is an afternoon in autumn, near dusk. The western sky is a spider’s web of translucent gold. I am being brought by carriage—two horses—muted thunder of their hooves—along narrow country roads between hilly fields touched with the sun’s slanted rays, to the village of Princeton, New Jersey. The urgent pace of the horses has a dreamlike air, like the rocking motion of the carriage; and whoever is driving the horses his face I cannot see, only his back—stiff, straight, in a tight-fitting dark coat.

Quickening of a heartbeat that must be my own yet seems to emanate from without, like a great vibration of the very earth. There is a sense of exhilaration that seems to spring, not from within me, but from the countryside. How hopeful I am! How excited! With what childlike affection, shading into wonderment, I greet this familiar yet near-forgotten landscape! Cornfields, wheat fields, pastures in which dairy cows graze like motionless figures in a landscape by Corot . . . the calls of red-winged blackbirds and starlings . . . the shallow though swift-flowing Stony Brook Creek and the narrow wood-plank bridge over which the horses’ hooves and the carriage wheels thump . . . a smell of rich, moist earth, harvest . . . I see that I am being propelled along the Great Road, I am nearing home, I am nearing the mysterious origin of my birth. This journey I undertake with such anticipation is not one of geographical space but one of Time—for it is the year 1905 that is my destination.

1905!—the very year of the Curse.

Now, almost too soon, I am approaching the outskirts of Princeton. It is a small country town of only a few thousand inhabitants, its population swollen by university students during the school term. Spires of churches appear in the near distance—for there are numerous churches in Princeton. Modest farmhouses have given way to more substantial homes. As the Great Road advances, very substantial homes.

How strange, I am thinking—there are no human figures. No other carriages, or motorcars. A stable, a lengthy expanse of a wrought iron fence along Elm Road, behind which Crosswicks Manse is hidden by tall splendid elms, oaks, and evergreens; here is a pasture bordering the redbrick Princeton Theological Seminary where more trees grow, quite gigantic trees they seem, whose gnarled roots are exposed. Now, on Nassau Street, I am passing the wrought iron gate that leads into the university—to fabled Nassau Hall, where once the Continental Congress met, in 1783. Yet, there are no figures on the Princeton campus—all is empty, deserted. Badly I would like to be taken along Bayard Lane to Hodge Road—to my family home; how my heart yearns, to turn up the drive, and to be brought to the very door at the side of the house, through which I might enter with a wild elated shout—

I am here! I am home!

But the driver does not seem to hear me. Or perhaps I am too shy to call to him, to countermand the directions he has been given. We are passing a church with a glaring white facade, and a high gleaming cross that flashes light in the sun; the carriage swerves, as if one of the horses had caught a pebble in his hoof; I am staring at the churchyard, for now we are on Witherspoon Street, very nearly in the Negro quarter, and the thought comes to me sharp as a knife-blade entering my flesh,

Why, they are all dead, now—that is why no one is here. Except me.