My Guantanamo Diary (15 page)

Read My Guantanamo Diary Online

Authors: Mahvish Khan

Burkas and veils are hard for Westerners to understand. Many associate democratization with women throwing off their burkas. But my father described Afghanistan before the Soviet invasion and before the Taliban era as a peaceful place where women with stylish haircuts wearing miniskirts strode in the streets alongside other women in burkas. It’s inaccurate for the media to portray burkas as simply a new, Taliban-era edict. The Taliban may have forced all women to wear them, but there have always been Afghan women who choose to wear them on their own. My paternal grandmother was one. Nobody forced her to don the burka, neither her husband nor any other male relative. My dad, in fact, used to try to persuade her to wear a shawl instead. But everyone says she preferred the burka.

We had been driving for several hours, and my camera was being passed around the car so that everyone could help get the best angles for various photographs. But the other passengers were still reserved and didn’t speak directly to me. I drew curious glances, though, when they heard my accented Pashto.

“Her Pashto sounds as though she has spent time outside,” the man next to Munir finally said. Munir explained who I was

and what I was doing. The Afghan from Germany turned around to face me.

“God keep you. I am very happy you have come,” he said, nodding his head. He reminded me somehow of Dr. Ali Shah Mousovi.

In the Sarobi mountains, we came to another roadblock. Fortunately, this time there was no shooting. A Chinese road crew was rebuilding the road, which had been barely drivable for years. It was bombed heavily during the U.S. invasion and was largely unmaintained during the Taliban era. But with the help of international workers, it is being rebuilt to allow for easy commerce between Peshawar and Kabul.

Half an hour later, the road crew let us through to the Afghan capital.

KABUL

I checked into Ariana guesthouse in downtown Kabul, a large house with gardens and a friendly staff. I was surprised to find the room charge to be $50 a night; that’s cheap for the United States but a lot for Afghanistan. The cost of living in Kabul had skyrocketed after the fall of the Taliban because of the rise in foreign aid workers from organizations such as the Red Cross, the United Nations, and various international businesses and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). In fact, Kabul’s posh downtown commercial and high-end residential Wazir Akbar Khan district is now more expensive than many U.S. cities.

At first glance, my room seemed comfortable. The two-man hotel crew dragged in a big heater, but they told me to turn it off at night so that I wouldn’t die of carbon monoxide poisoning. I wanted to take a shower, but the water was icy. The crew came in (after knocking and asking for

ijaazat,

or

permission to enter) and turned the water heater on, but it wouldn’t work.

The hotel staff boiled some water on the kitchen stove and brought it to my room in a big red plastic bucket. It was scalding hot, so I mixed it with cold water in an empty Coke bottle, then “showered” by pouring the water from the bottle over my head. Afterward, I realized that there weren’t any towels; I drip-dried in front of the carbon monoxide gas heater.

To add to the Third World experience, the electricity kept going in and out. I was freezing but afraid of the poisonous gas coming from my heater. I figured it was better to freeze than to be gassed in my sleep, so I turned the heater off. The next morning, I woke up early. I knew I wasn’t being fussy when I exhaled and saw my breath.

I had an interview set up with Abdul Salam Zaeef, a former Taliban ambassador and Guantánamo detainee. Once again, I was looking forward to a hot shower, but the water was still icy, so I jumped in and out quickly and gave myself a head-freeze washing my hair. I was trying hard to go with the flow, but I didn’t think I could last for two weeks with hypothermia and the constant threat of carbon monoxide poisoning. My blow dryer wasn’t working because the electricity was going on and off, so I just covered my wet hair with a black shawl.

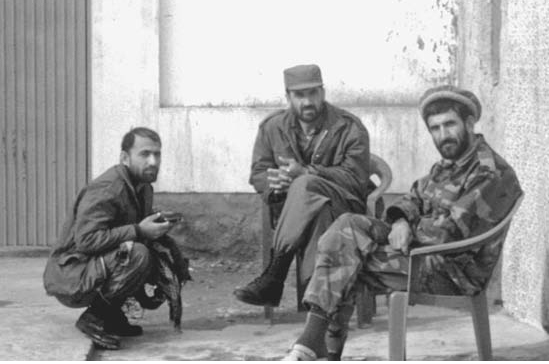

I took a cab to Zaeef ’s mansion in Kabul’s Khushal Khan neighborhood, feeling very nervous about meeting the outspoken former Taliban ambassador. I’d gotten in touch with Zaeef through local journalists who had written about him and who had helped me request an interview. As I got out of the taxi, I counted ten armed guards outside the ambassador’s gated complex. Some were wearing camouflage and boots, but one wore plastic sandals with socks. Two were sitting in blue plastic chairs with their legs crossed. Another squatted in the driveway holding a gun. They seemed to be expecting me and were at ease. A man waiting by the gates escorted me into a room lined with gray sofas, where I sat down to wait.

Abdul Salam Zaeef’s guards outside his Kabul home.

Author photo.

Zaeef became notorious when he made himself the public face of the Taliban by holding regular news conferences after September 11. While he publicly condemned the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, he maintained that Osama bin Laden was not responsible. When the situation got a bit dodgy in Afghanistan, Zaeef fled from the bombs to neighboring Pakistan, where he sought asylum and continued his media attacks on the U.S.-led war. Soon after,

he was arrested in Islamabad by the Pakistani Secret Police, handed over to the U.S. military, and eventually wound up at Gitmo.

I was particularly curious about him because of his former political affiliations. I wanted to pick his brain about his former job as ambassador for the Taliban. Dechert was supposed to have represented Zaeef, but he was released in the summer of 2005 before Peter Ryan and I ever had the chance to meet him. I also thought it was peculiar that he’d been arrested at all, since international law dictates that he should have received diplomatic immunity.

When he walked in and greeted me, my nervousness didn’t immediately dissipate, although I was surprised to find him very soft-spoken. He was a tall, big-boned man with a thick, dark beard and eyeglasses. He was wearing a light-colored blazer over his Afghan clothes. He sat down across a glass table from me, and I was relieved that he apparently had no qualms about a woman interviewing him, although all he could see of me were my face and hands. A thin man came in and poured us green tea. I was freezing and quickly took a gulp, burning my lips.

Zaeef curled up in the sofa chair, drawing in his sock feet. He told me he was through with politics and was happy at home with his two wives and six kids, writing another book.

Over the next two hours, we downed a pot of green tea, and I picked his brain. I started off with questions related to his experiences at Gitmo and worked up the courage to ask him about how he’d justified working for a regime that allegedly executed women in a sports stadium.

Here are some excerpts of our chat:

- Q:

You were at Gitmo for three years and five months. Did you always cling to a hope that you would go home? - A:

No, in the beginning, I had no hope. When I was first brought to Guantánamo, it brought back memories of the Russian invasion of Afghanistan. Thousands of Afghan men disappeared [during that war]. I feared a similar fate. It was only after I saw other Afghans going home that I slowly allowed myself to hope that I might too. I knew I had not committed a crime, so I had hope that someday I would be released. - Q:

What was it like when you were finally released? How did you get the news? - A:

I was in Camp 4 with Haji Nusrat and his son Izatullah when I got the news. The soldiers came with the Red Cross and told me I would be going home. All of the other prisoners congratulated me. They asked me to visit their families and convey their greetings. - Q:

Tell me about actually going home. What was the plane ride like? I’ve heard that prisoners are sent home in shackles. Were you shackled on the way home? - A:

Well, I had never seen the Guantánamo Airport before because prisoners are always moved around in special windowless vehicles. It was night time, and when I got there, there was a general standing on the tarmac. His name was written on his shirt, but I don’t remember it. . . . He congratulated me.

He told me I’d been through a lot of hardships but that I was a good person and that I was headed home. Then, he told two soldiers to free me. They cut my plastic handcuffs. There was a soldier on each side of me, and they led me to the plane. There was also a delegate from the Afghan government there, and he congratulated me. - Q:

What did it feel like to be unshackled for the first time in years? - A:

I thought I was in a dream—that none of it was real. I was in a special plane; I was unshackled. It was the first time in years that I could eat and move my legs freely . . . and decide when I wanted to eat. It was a strange experience. - Q:

What did you feel? - A:

I felt many things. I was feeling guilty for everyone left behind. I was excited to be leaving Guan-tánamo. But at the same time I was very anxious, very nervous. - Q:

Nervous how? - A:

I was nervous about where I would be taken. I was afraid I might be jailed somewhere else. - Q:

Are you able to separate the American people from their government? - A:

It is hard to separate the two. Right now, I am hating most Americans. - Q:

Why? - A:

Initially, I thought it was the policy makers and the American government that were to blame— not the American people. But the American people

voted for Bush a second time. Although I do believe the American government has taken the American people hostage. They live in fear of their government’s lies. - Q:

Would you ever visit America? - A:

No. I have no interest in that. - Q:

How do you justify your work as a representative for a regime that executed women in the sports stadium? - A:

That incident was televised all over the Western media, but what Americans do not know is that this lady was sentenced to death for murdering her husband. It had nothing to do with adultery. Don’t Americans also have the death penalty? Would it make it better if she were executed in private? - Q:

Tell me about some of your interactions with the guards at Gitmo. - A:

I was always talking to them. I was explaining my situation to them and I was always inviting them to Islam. - Q:

How’d that go over? - A:

Sometimes they listened. Sometimes they didn’t. I always told the guards that if they had objections to Islam, I was ready to speak to them about it. Some people had no idea what Islam was really about. I thought it was my responsibility to expose them to true Islam.

Alhamdulillah

—praise be to God—two became Muslim. - Q:

Tell me about that. - A:

Two white soldiers, they accepted Islam after speaking with me for three or four months. They kept it a secret. They would come to me, wake me up, and I would talk to them. I wish I could meet those two again, but I don’t know their addresses or how to find them. - Q:

What were their religions before? - A:

One was an atheist, and the other was Christian. There were other soldiers who didn’t convert but were intrigued enough to listen to me and told me they would speak to an Islamic scholar when they returned to America. I was always trying to educate people about the religion; they know so little and have been so prejudiced. When I was called into interrogations, I would do the same thing there. Sometimes they would tell me they weren’t interested in listening, but many of them were open minded.

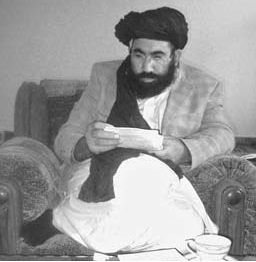

Abdul Salam Zaeef rereading family

letters received at Guantánamo.

Author photo.

Before I left, I photographed Za-eef sifting through a thick stack of his Guantánamo letters, many of them covered in dark censor strokes. He told me that letters were everything to prisoners. Now, they evoked painful memories, but he hung on to them. He echoed what so many of the released have said about Guantánamo: “It’s a part of me now.”

He also showed me a photograph of his daughters that he kept in his cell at Gitmo (at right).