My Guantanamo Diary (16 page)

Read My Guantanamo Diary Online

Authors: Mahvish Khan

As I hopped into a cab, I decided to check out of my hotel and go someplace with a generator and central heating. I asked the driver to take me to the Inter- Continental Hotel. It was only ten minutes away, but traffic was very heavy, and it ended up taking half an hour to get there. The driver made small talk. He asked me what I was doing and where I was from. I told him a bit about myself but omitted the part about America. But that was the part he was wondering about.

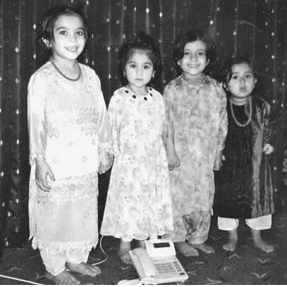

A photo of Zaeef ’s daughters, which he

kept in his Gitmo cell.

Courtesy of Abdul

Salam Zaeef.

“But where is your home?” he asked. “You sound like you have spent time abroad.”

Amreeka kay usaygam

—I live in America,” I finally said. “

He looked at me in the rearview mirror and smiled. “How fortunate you are.”

“This is my first time in Afghanistan. It’s really beautiful,” I said.

He started to tell me about his troubles. He had salt-and-pepper hair and six- or seven-day stubble. He wore an embroidered hat and honked the horn brazenly as he wove through traffic, all the while telling me about an entire generation of Afghan youth left without education because of war.

“Without education, sister,” he said, glancing back at me, “our future is bleak.”

Afghans hated the Taliban and lived in fear during their rule, he said. “God damn them for what they brought upon us,” he said angrily. Unlike many others, he could not afford to flee to Iran, Pakistan, or overseas. He told me that I should know about the hardships all Afghans face every day. He told me about his struggles to take care of his young children and his wife. We talked about the Russian invasion, the Taliban, the land mines littering the country, warlords, and U.S. bombs.

He drove onto the InterContinental’s long uphill driveway, stopping at several gates and various levels of security checkpoints where armed guards questioned him and peered into the trunk. They waved us through. When we pulled into the hotel parking lot, I handed him some extra dollars. He put his palm against his chest and nodded. According to the Afghan ministry of finance, the average Afghan makes about eighty cents a day. Up to that point, I had only known about the economic, social, and psychological effects of perpetual warfare from accounts by journalists, historians, and statisticians. I knew that the separation between the rich and poor was great, but beyond the dates and figures, I had no experience of it.

I had also heard a lot about developments in infrastructure, commerce, and education since the Taliban had been ousted, but I was still surprised when I saw the InterContinental. The taxi driver insisted on walking me in with my bags. We passed a large sign with a picture of a machine gun and a large red

X

drawn over it. “No Weapons,” it read. A doorman held open the glass doors to the lobby. I stood behind a barricade of red velvet ropes. The doorman told the cab driver to put my lug-

gage on the table, where it was searched. Then, another man with a black mustache, wearing a blue suit, instructed me to walk through a metal detector into the chandeliered lobby.

I had no idea that Kabul had such a revamped hotel. I quickly discovered the InterContinental’s ostentatious list of amenities. All of a sudden, my taxi driver looked out of place in his tattered clothes and dusty shoes. He must have felt it too, because he hurriedly gave me a small card with his number, in case I should need him again. I thanked him profusely and said goodbye.

The hotel is a huge complex; all charges were to be paid in dollars only. I was surprised to see an ATM machine in the lobby—and further surprised when it dispensed U.S. dollars. The restaurant and room service menus listed a variety of American and Afghan cuisine with prices listed in U.S. dollars. An “American hamburger” was $8.

The complex included a spa, a business center—which charged by the minute, in dollars—a team of imported young Thai masseuses, a hair and nail salon, a ballroom, a swimming pool, restaurants, a tea and coffee house with huge dark leather couches, and a wide variety of imported teas and coffees. The hotel was full of businessmen, tourists making weekend trips from Dubai, and, as a hotel employee would tell me later, Afghan and U.S. intelligence spying on guests. Some of the rooms, I learned later, were bugged.

The hotel also had an airline counter and numerous small gift shops. When I asked one shop keeper how he justified his ridiculously inflated prices, in dollars, he told me that a small gift shop space at the hotel was $800 a month—and highly coveted.

The clerk at the front desk quoted me a rate of $160 per night. It seemed obscene for Afghanistan. I looked at him in

disbelief and started to haggle. “I can’t afford more than $100,” I said firmly.

“Okay. We accept cash only. Dollars,” he said.

He asked me to pay for a few days in advance.

I was surprised when he handed me a modern key-card to my room. As I walked across the lobby to the elevators, I saw Westerners in jeans standing around speaking French. There were couples sitting on couches being served big slices of yellow cake and tea. The place was crawling with North Atlantic Treaty Organization soldiers, European adventure seekers, and other tourists browsing the antique jewelry shops. It was a weird oasis.

At the elevator, I was greeted by a guard.

“Which floor, madam?” he asked in English.

“Eight, please.”

Hardly anyone at the hotel wore Afghan clothes. None of the women covered their hair, and all of the employees spoke English. It was often broken English, but they were obviously instructed to speak it.

In my room, I plugged in my laptop and went online. I felt guilty paying so much for a hotel room when most Afghans didn’t have running water or electricity in their homes. Here, I had central heating, a huge bathroom with hot water, and high-speed Internet.

I e-mailed my family to let them know that I was fine. Then, I slipped into a pair of flats, wrapped myself in a pashmina, and prepared for my meetings with the families of detainees. Each day, I visited a former Gitmo prisoner or the families of men still imprisoned. The families were instrumental in helping gather evidentiary documents used in the

detainees’ defense. For example, the U.S. military didn’t seem to buy that Abdullah Wazir Zadran was a shopkeeper selling tires in the Khost bazaar with his family. So, I asked his older brother Zahir Shah to collect photographs of the tire store. We also discussed getting affidavits of neighboring shopkeepers to give to the military courts. Zahir Shah brought a stack of about fifty photographs of the tire store with the family name clearly written on the sign above it. I held many of these meetings at the hotel because I was nervous about venturing into southern Afghanistan.

After my work for the day was done, I headed into the city. I loved the hotel’s comforts but was eager to get outside its gates. I wanted to see the real Kabul.

At the front desk, I asked one of the mustached men to help me hail a cab so I could explore the city.

“Are you going alone?” he inquired. “We can send someone with you if you prefer.”

The hotel’s Ariana Airlines desk officer closed the office and said he’d take me around. He had a short beard, and I immediately noticed a huge scar along the left side of his face and wondered what it was from. When our discussion eventually turned political, he explained that he had been beaten by the Taliban years before. He couldn’t afford to flee, as many of his friends had.

“There is no way I could have walked the streets with this short beard,” he said. “And there is no way we could have walked together. It was a terrible time.”

He took me first to Chicken Street, a narrow lane lined with small shops selling everything from antique water jugs to handcrafted Afghan rugs, as well as the imported Persian variety. I picked up two, one for me and one for Peter Ryan. I wandered from store to store, checking out the antique jewelry, embroidered shawls, and jeweled, wooden boxes with hand-painted Persian hunting scenes. I picked up a rabbit fur jacket for $30 and a bunch of large dangly antique silver earrings. While the prices on Chicken Street were much more reasonable than at the gift shops at my hotel, I still wondered how Afghans could afford Kabul. Everywhere I went, I saw European men and women shopping.

After Chicken Street, my guide gave me a tour of Kabul. It seemed like everywhere we looked, there was bogus development. I saw little evidence of urban planning, or a desire to close the open sewage lines, or hospitals or schools. Instead, the city had seen a spike in high-end hotels, Internet cafes, bars, and swimming pools, which I was told were surrounded in the summertime by European women in bikinis. At first, I didn’t know what to make of it all. But the more I saw, the more it irked me. Living costs in Kabul are just as high as (or higher) than they are in the United States.

Before the U.S. invasion, it would have cost $50 to $60 monthly to rent a small house near Kabul City. Now the price had been hiked up to $1,500 a month. But in the upscale Wazir Akbar Khan district of Kabul, prices were insane. It used to cost about $300 a month to rent a nice house there. Now, prices had soared from $5,000 up to a whopping $15,000 a month—higher than the cost of living in most areas of Beverly Hills.

All this so-called development wasn’t for Afghans or even for Afghanistan. It was for European and American NGOs, for people who chat up their sat phone bills and hook up their Sony Vaios at cybercafes. These were the sorts who stayed at the InterContinental— or Kabul’s new decadent Serena Hotel, where guests could drop $350 a night for a room or $1,200 a night for a presidential suite. The average Afghan would have to work for more than four years to be able to afford a single night there.

When I visited the Kabul City Centre, a massive, multimillion dollar megamall with shiny golden escalators and glass elevators, it was more of the same. Rich Europeans, Americans, and Afghans who lived abroad were passing their time shopping for high-end electronics, designer clothing, precious stones, Swiss watches, and antiques. The stores displayed limited-edition U2 iPods and multiple-stranded ruby and emerald necklaces. The only currency accepted was dollars. With the holiday season fast approaching, there were signs for Christmas specials everywhere. It seemed a little odd in a predominantly Muslim country.

Outside the mammoth mall of decadence, it was another story. The typically proud Pashtuns had resorted to begging. It was the only way to benefit from the grand development going on all around them. Afghan boys and girls in tattered clothing gathered in the piercing cold winter winds. They held out their dirty hands, hoping that a wealthy shopper would take pity. Some had lost legs to land mines and dragged their bodies across the icy pavement as shoppers mostly averted their gazes and walked quickly toward warm waiting Land Rovers.

The UN Department of Humanitarian Affairs estimates there are about ten million land mines scattered throughout Afghanistan, many of them remnants of the 1980s Russian invasion. An estimated eight hundred thousand Afghans have been maimed by the devices in the ensuing decades. UNICEF estimates that twenty to twenty-five people are wounded every day and that 4 percent of the Afghan population has been disabled by exploding land mines. You could see the legless people on crutches or in wheelchairs everywhere.

Children playing in Kabul.

Author photo.