Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (34 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

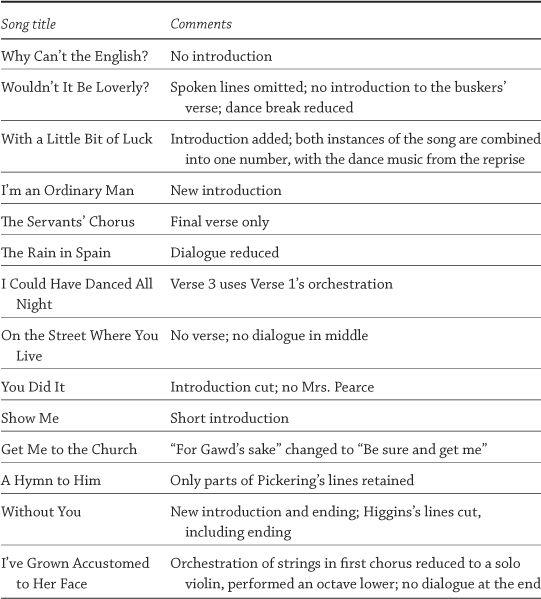

Table 7.1.

Examples of changes made to the text for the original cast album

The three principal members of the original cast continued until November 28, 1957, when Rex Harrison left the show.

7

Stanley Holloway succeeded him on December 13, 1957, when he was granted permission to sever his contract early in order to be able to sail home on the Queen Mary before Christmas.

8

Julie Andrews also asked to leave the show a little earlier than planned in order to have more of a break before starting rehearsals for the London production of the show. However, because Sally Ann Howes, who was to take over from Andrews,

9

was not available until February 3, 1958, Herman Levin refused Andrews’s request, even though Lerner and Loewe were willing.

10

This meant that she departed on February 1 as originally planned, and started rehearsals for the London version on April 7.

Sally Ann Howes as the second Broadway Eliza Doolittle in

My Fair Lady

(Photofest)

Filling the original cast’s distinguished shoes was by no means an easy task. As early as 1956, Levin was already in discussion with agents about possible replacements. For instance, the British character actor Bill Owen auditioned for Doolittle’s part, but after prolonged deliberation Levin balked at the idea of paying him $1,000 per week.

11

Lerner and Loewe also went to London to audition stage star Douglas Byng, but eventually Ronald Radd, best known for his television appearances, was hired to replace Holloway.

12

Levin also had ambitions to have major names succeeding Harrison in the role of Higgins: a letter dated March 20, 1956, indicates that the producer once more tried to interest Michael Redgrave in the show, even though it had only just opened on Broadway.

13

Since Harrison was committed to the production for only twelve months, Levin was concerned about sustaining its initial success: a telegram from Lerner to Levin on November 15, 1956, indicates that they had managed to get John Gielgud to agree to portray Higgins until March 1957 if Harrison refused to extend his contract. Lerner and Levin were intending to use Gielgud’s commitment as a bargaining tool: “We can no[w] put pressure on Harrison to sign at least till June or lose London.”

14

This reveals how important it was to Harrison to introduce the musical to British audiences.

A month later, Moss Hart took the role to Noël Coward, another star name who had been associated with the show at an early stage, but was again turned down.

15

In the end, Harrison’s replacement was Edmund Mulhare, an Irish actor without Harrison’s star name but who had filled in for his predecessor during vacations. Robert Coote (Pickering), Cathleen Nesbitt (Mrs. Higgins) and Christopher Hewitt (Karpathy) had long left the show, so with a fresh cast to review, Brooks Atkinson wrote an extensive article about the show on March 9, 1958.

16

He acknowledged that the new cast had “not been able to duplicate perfection,” but still raved about the quality of the writing, design, and production. Nothing could stop

My Fair Lady

now. On July 12, 1961, it became the longest-running musical in Broadway history, and through several more cast changes, plus two changes of theater (to the Broadhurst and Broadway theaters) in the final year of the run (1962), it was clear that the public had taken the show to its hearts, regardless of who was in it.

17

One curious aspect of its reception was the number of parodies that were written, especially during the original run. For example, in 1957 the composer Dean Fuller and the lyricist Marshall Barer wrote a sketch titled “My Late, Late Lady” for the

Ziegfeld Follies

, starring Beatrice Lillie; among the references to

My Fair Lady

was a pastiche of “The Rain in Spain” containing the lines “the sink doesn’t stink any more” and “I had a bawth last night.”

18

Another, more lasting project was a spoof recording put out on the Foremost record label in 1956, called

My Square Laddie

. This turned the

Fair Lady

story

on its head and had Broadway veteran Nancy Walker (who had appeared in shows such as

On the Town

) teaching British actor Reginald Gardiner how to speak in an authentic Brooklyn dialect. Again, the references to Lerner’s lyrics are numerous, with such song titles as “What Makes a Limey Talk so Square?” “It’s De Oily Boid,” and “I’m Kinda Partial to his Puss.”

19

These and other such attempts to cash in on the success of

Fair Lady

invoked consternation in the Levin camp, yet in retrospect they are fascinating as items that show the extent to which the musical had been absorbed into American culture.

My Fair Lady

was always a natural choice for London’s theater scene. As early as 1952, when Lerner and Loewe were still pursuing Mary Martin to play the role of Eliza, they even considered giving the piece its world premiere in the city of its original setting. The original London production was unusual in containing all four of the Broadway principals; notwithstanding isolated examples such as Mary Martin’s appearance in the original London

South Pacific

, it was almost unheard of for a major Broadway show to be brought to England with production and cast practically in tact. Evidently, Harrison, Andrews, Holloway, and Coote wanted to return home victorious after conquering Broadway. Tickets for the London production went on sale on October 1, 1957, and Reuters reported that on the first day alone, more than $15,000 was taken by the box office (which was accepting sales up to October 1959).

20

Hugh Beaumont was finally able to benefit from the deal he had made with Levin in 1955 to release Harrison from

Bell, Book and Candle

so that rehearsals for

Fair Lady

could begin: the right to produce the show in London automatically gave him control over the hottest ticket in the West End. To complete the cast, he chose Betty Wolfe as Mrs. Pearce, Leonard Weir as Freddy, and Zena Dare as Mrs. Higgins. A veteran of the West End, Dare made her final stage appearance in this show. She stayed with the production for the entire five-and-a-half-year run, then going on tour with it until she decided to retire completely. Another important figure in the British production was Cyril Ornadel, a renowned West End musical director who also had considerable success as a composer of musicals.

21

Loewe was unable to attend the London opening because he had suffered a heart attack on February 26 before he was due to leave New York. Hart, Levin, and Lerner had to go to London and open the show without him.

22

The premiere took place on April 30 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and the success of the Broadway run was repeated. In spite of such high expectations,

arguably heightened because of the reverence for Shaw in England, the London critics were largely very positive: the

New York Times

described it as “triumphant,” the

Evening News

said that it “came near perfection,” and the

News Chronicle

even went so far as to note that “the critics themselves looked excited for once.”

23

Kitty Carlisle Hart commented that “In London everyone was in a fever of excitement. The British felt that it was Shaw and Eliza Doolittle coming home.” After a triumphant premiere on April 30, the Queen and Prince Philip attended a Royal Command Performance on May 5, coming backstage to meet the cast following the show.

24

The production went on to run for 2,281 performances, again a huge achievement, especially given the much larger capacity of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (with more than 2,000 seats), compared to the Mark Hellinger on Broadway (approximately 1,500 seats). So successful was the London incarnation of the show that Columbia decided to record the British version, even though the four principals were the same. The introduction of two-track stereo recording equipment had taken off since the mono recording of the Broadway cast was made, so the opportunity to make a stereo version was irresistible. The recording took place on February 1, 1959, again under the direction of producer Goddard Lieberson. In general, the vitality and spontaneity of the original is not quite present on the London cast album, no doubt because the stars had performed it so many times, but Julie Andrews has recently declared her preference for the stereo version (which she describes as being “light years better than the original”).

25

The international distribution of

My Fair Lady

was extraordinary for its time. Although it was by no means the first show to travel beyond the English-speaking peoples, it achieved an unprecedented success in important cities all over the globe, the only major exception being Paris. Australia was the first of many countries to follow the West End production in replicating the Broadway original in January 1959, and it was followed by locations as diverse as Germany (1961), Iceland (1962), Vienna (1963), Japan (1963), Italy (1963), and Israel (1964).

26

By far the most curious, though, was the ten-week tour of Russia undertaken in 1960. Never before had a musical been the subject of international diplomacy in the way that

My Fair Lady

became at this time. On May 6, 1959, the

New York Times

published an article indicating an interest in seeing the show travel to Moscow. Nikolai N. Danilov, Soviet Deputy Minister of Culture, had issued an invitation to bring the production to Russia as part

of an ongoing series of Soviet-American cultural exchanges designed to foster better relations between the two nations during a difficult period of the Cold War. Levin had not been involved in the talks at this stage, but he was eager to be in charge of the tour, which he viewed as the beginning of a European tour that would then visit major cities all over the Continent.

27

Initially, these plans were delayed as Lerner and Loewe objected publically to a separate Russian production of the show, to be given in translation, for which the authors would receive no royalties. The mastermind behind the production was a thirty-year-old Russian called Victor Louis, who thought nothing of requesting the orchestration from Lerner and Loewe while openly admitting that they would receive nothing in return.

28

This was front-page news in the

New York Times

, but instead of bringing the Russian

Fair Lady

to an end, it encouraged Danilov—only a few days later—to go ahead and invite the Broadway company to take their production to Russia. Taking a production of

Fair Lady’s

complexity (including the two turntables for Oliver Smith’s set) to Moscow, Leningrad and Kiev, each with very different theaters, caused numerous logistical problems for Jerry Adler and Samuel Liff, the stage manager and production supervisor respectively. Ironically, Lerner and Loewe waived their royalties for the tour, in order to offset spiraling costs—a sign of how important the tour had become to them.

29

But it became a triumphant success. The eighty-one-person company was greeted enthusiastically by the Russians, and all fifty-six performances were sold out. Franz Allers went with them to conduct the orchestra, which was drawn from the Bolshoi Theatre, and both the show itself and the cast (including Edward Mulhare as Higgins, Lola Fisher as Eliza, and Charles Victor as Doolittle) all received a rave review in the Soviet Culture newspaper from Grigory M. Yaron, a leading actor and director of the Moscow Operetta Theatre. The

New York Times

deemed it a landmark event in Russian-American relations, representing a new step in the development of

Fair Lady’s

growing international reputation.

30