Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (33 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

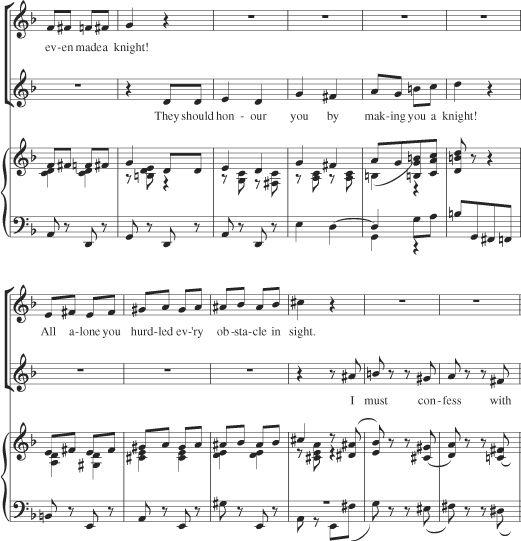

The other change was probably for musical rather than dramatic considerations. Originally, the final section of the song—when Pickering and the servants sing a contrapuntal passage following “Congratulations, Professor Higgins!”—was more extensive (see

appendix 5

). The published version contains only the first and last stanzas of this initial lyric (with a couple of minor changes), and the majority of the material at this point was cut. Interestingly, this music contains a different gesture to anything else in the show (partly quoted in

ex. 6.7

). Although the “Congratulations!” passage is contrapuntal even in its published form, the antiphonal effects between Pickering and the servants in the original version made the number stiffer, more like an operetta ensemble, and thereby more old-fashioned. In spite of William Zinsser’s insistence that Lerner and Loewe “were a throwback to the earlier generic team of Gilbert and Sullivan” and that Loewe’s music “continued to sound Viennese,” the composer in fact removed the passage of music that most connected the show to these styles of composition.

49

Ex. 6.7. “You Did It,” cut passage.

This cut also represents an act of compression: it drives the piece home more quickly, more smoothly, and more breathtakingly. One notable aspect of the passage was the return of a second earlier theme (“I must confess without undue conceit,” deriving from “Now wait, now wait, give credit where it’s due”) in addition to the “You did it!” theme. The latter remained in the published version but only as a contrapuntal underpinning of the new “Congratulations!” theme; the barer “I must confess” part and the antiphonal section as a whole draw attention to themselves more assertively. By removing them, Loewe gave the closing section the air and function of an operatic

stretta

but foreshortened it to avoid direct allusion.

Loewe’s triumph in

My Fair Lady

was to create a score that truly enhances the potential of

Pygmalion

yet without overwhelming or undermining that text

with extraneous musical numbers. Surely “Why Can’t the English?” depicts Higgins’s character better than any dialogue could, while the lessons sequence is a series of musical scenes with little precedence in the musical theater repertoire. This also represents a clear enhancement of Shaw’s text. Furthermore, theatrical technique is apparent throughout the score; for instance, “The Embassy Waltz” is a compelling use of musical diegesis, where the music is both part of the onstage action and expressive of the emotion of the scene. As for musical technique, the range of compositional approaches is brilliant, whether in the use of dance forms in the creation of songs like “Show Me” and “Just You Wait” or large-scale forms as in “You Did It,” as is the no less impressive way in which Loewe binds it all together. In this, he shares the credit with his colleagues: Rittmann’s arrangements and the orchestrations of Bennett, Lang, and Mason helped make the score contrapuntally taut and gave it its magical palette of sonorities.

But in the end, Lerner and Loewe’s most impressive achievement was the way in which they eventually balanced the Higgins-Eliza relationship in their songs. We have seen numerous examples of songs discarded as inappropriate (“There’s a Thing Called Love”), replaced by better numbers (“Please Don’t Marry Me” into “An Ordinary Man”), replaced by songs with a completely different subtext (“Shy” into “I Could Have Danced All Night”), or refined to remove gestures of conventional romance (“You Did It”). Although it is relatively commonplace for large numbers of songs from Broadway shows to be discarded before completion or cut before opening night, it is rare to find quite such a clear motivation for their removal as in

My Fair Lady

.

PERFORMANCE HISTORY

MY FAIR LADY

ON STAGE

The performance history of

My Fair Lady

has been characterized by long runs and critical success. The original Broadway production ran for more than six years and 2,717 performances, and in so doing overtook Rodgers and Hammerstein’s

Oklahoma!

to become the longest-running Broadway show to date; it maintained this record for nearly a decade. The original cast won almost universal raves, both on Broadway and in London, and in 1964 the show went on to be adapted into one of the most successful movie musicals of all time, winning eight Academy Awards. The show was also seen internationally, including a tour to Russia at the height of the Cold War as part of a goodwill exchange with America. Broadway revivals in 1976 and 1981 returned to the original designs, choreography, and direction for inspiration, and three of the original 1956 cast members returned to their original roles. A further revival in 1993 continued this pattern, as Stanley Holloway’s son, Julian, took on his father’s role of Alfred Doolittle. Trevor Nunn’s 2001 production at London’s National Theatre quickly transferred to the West End, where it ran for 1,000 performances before touring first the UK and then the United States to mark the musical’s fiftieth anniversary. A new film version is currently in pre-production, which will make it one of the few musicals from Broadway’s golden age to enjoy two big-screen adaptations. Clearly, the show has a special place in the repertoire. This chapter explores its legacy in the theater, both in terms of trends and gestures in productions of the piece and how it was received by critics.

Variety

was one of the first publications to review the show. Its critic saw the premiere at the Shubert Theatre in New Haven on January 4 and reported: “[The show] has so much to recommend it that only a radical (and highly

improbable) slipup in the simonizing process can keep it out of the solid click class.”

1

This was the first of many ecstatic responses that the work would receive and is littered with gushing statements such as “George Bernard Shaw … never had it so good as with this lavish production,” “a glove-fitting score,” “stellar direction,” and “a general aura of quality.” A week later,

Variety

published a short article stating that fifteen minutes of the show’s running time was cut during the New Haven run (which ended on February 11), largely consisting of the “Come to the Ball” number. “Say a Prayer for Me Tonight” and the “Decorating Eliza” ballet were reported to have been cut after the New Haven closure but before the start of the Philadelphia tryouts on February 15. The article also said that “Local reaction to the musical set a new high for the last six years, rivaling that for the break-in stand of

South Pacific

at the same house in the spring of 1949.”

2

This critical and popular success was to be more than matched when the show reached Broadway. The early reviews underline certain elements of the work that continue to inform its critical reception to this day. The first is the musical’s Shavian precedent, which was mentioned by all the reviewers. This is one of the points on which they were most divided. Some were highly complimentary of Lerner and Loewe’s work; for instance, Robert Coleman in the

Daily Mirror

said that Lerner’s lyrics had “kept the essence of the original” and that they “beautifully complement the Shavian dialogue.”

3

Similarly, William Hawkins in the

New York World-Telegram

claimed that

Pygmalion

“has been used with such artfulness and taste, such vigorous reverence, that it springs freshly to life all over again.”

Most of the other leading critics made a point of attributing much of the musical’s success to Shaw. John Chapman’s review for the

Daily News

described

My Fair Lady

as a “musical embellishment of Bernard Shaw’s romantic comedy,” and went on to say that Lerner and Loewe “have written much the way Shaw must have done had he been a musician instead of a music critic.” The word “embellishment” here seems pointed; though not entirely pejorative, it portrays the composer and lyricist as having merely decorated something that was already there, rather than adapting the play as radically as they did. Similarly, Chapman’s comment about composing “as Shaw must have done” to some extent denies the imagination of Lerner and Loewe’s approach: it is as if their creation was pastiche rather than original. Three of the other reviewers were even more direct on the subject. John McClain’s

Journal American

review refers to the fact that Shaw’s text had not been “tamp[ered with] too much,” while Richard Watts Jr. in the

New York Post

wrote: “In handing out the allotments of praise, I suppose it would be a good idea to begin with Bernard Shaw. As a librettist, he is immense.” The latter comment

apparently puts Lerner out of the picture as the show’s book writer. Along similar lines, Brooks Atkinson’s review in the

New York Times

contained the comment, “Shaw’s crackling mind is still the genius of

My Fair Lady

.”

In sum, although all the critics seemed to have hugely enjoyed the musical, they were almost united in denying Lerner and Loewe credit for its success, in spite of Lerner’s large number of departures from Shaw in his book. Of course, they did have a point, since more of Shaw’s play remains in the musical than would normally be the case, but one of the reasons for their stance is probably that they were drama specialists who all revered

Pygmalion

, rather than music specialists with an interest in the process of making it into a musical. The comments on the music almost speak for themselves: “Unpretentious and pleasantly periodic” was McClain’s description; “robust” was Atkinson’s adjective for the score; “they certainly are clever” said Hawkins of the songs.

In addition to overemphasizing Shaw’s contribution and lacking the space (or knowledge) to do justice to Loewe’s music, the critics’ comments on the Eliza-Higgins relationship are fascinating, not the least because there is no consensus. Atkinson refers to “love music” and describes Higgins as “a bright young man in love with fair lady.” Coleman is likewise certain that Harrison is “the Pygmalion who falls in love with his creation,” and McClain mentions Higgins’s “revelation,” hinting at a “Cinderella” romance. John Beaufort agrees, stating that Higgins’s “single-minded preoccupation with Eliza’s education makes him almost overlook Eliza until it is too late.” On the other hand, Hawkins makes no comment on the subject, focusing on “the effort to make the lady of Eliza,” and the same goes for Chapman, Kerr, and Watts; none of these critics say that the characters are in love, or even seem to hint at it. This is a useful point of reference for subsequent interpretations of the piece: from the very start, the nature of Higgins and Eliza’s relationship was never absolutely defined.

This point was continued on March 25, when Brooks Atkinson returned to the show and wrote another article, headed: “Shaw’s

Pygmalion

Turns into One of the Best Musicals of the Century.”

4

The beginning and end of the new review refer to romance but hint that Atkinson is trying to backtrack from his firm portrayal of the supposed love between Eliza and Higgins. He admits that one of the other critics had pointed out that “the hero and heroine never kiss,” and that

My Fair Lady

“reflects Shaw’s lack of interest in the stage ritual of sex.” Significantly, Atkinson also discusses Shaw’s decidedly unromantic epilogue to

Pygmalion

, and in the phrase “Eliza’s life in an imagined future is beside the point” underlines a major issue: since these are characters rather than real people, they do not have “life” beyond the final curtain and cannot be assumed to be joined in matrimony. Aside from this,

Atkinson’s overwhelming message is simple: “

My Fair Lady

is the finest musical play in years.”

CBS’s financing of the original production was not merely a good investment because of the outstanding ticket sales. That their record label, Columbia Records, could put out the original cast album ultimately earned them a huge amount of money. On October 2, 1957, the

New York Times

reported that the album had sold over a million copies already. By March 3, 1962,

Billboard Music Week

was able to confirm that the LP had sold over 3.5 million copies to date; it was also the first album in history to exceed both two and three million sales. In the same article, it was estimated that the sales of the Broadway and London cast recordings had grossed over $15 million, on an investment of roughly $40,000.

5

These figures attest to the fact that the album was a phenomenon in itself; as a way of disseminating the content of the show to society in general, it had even greater impact than the stage production.

Goddard Lieberson, who was the producer of many Broadway albums for Columbia in this period, took the cast into the Columbia Thirtieth Street Studios on March 25 to record the show. As was usually the case, the album was to be recorded within a single day and released as soon as possible to maximize sales. (Symptomatic of the speed of turnaround is an error on the initial batch of albums, which retained the early title of “I want to dance all night” on the sleeve covers, because they were preprinted before the lyric change was made. Stanley Holloway’s billing was also smaller than agreed, and Phil Lang’s name was omitted.)

6

Also following tradition, the album was prepared based on providing the best aural experience for the listener, rather than simply recording what was heard in the theater. This had two main manifestations: changing details of the performance, and changing the text. In the former category, we can include modifications to the tempos—sometimes numbers would be done faster or slower in the theater according to the practical needs of the production, such as a scene change or accommodating a singer taking time to warm up at the start of the show—while the latter category includes increasing the number of players in the orchestra (for instance, to enhance the quality of the sound of the string section), re-arranging material, and omitting dialogue. Some of these considerations are especially interesting in relation to

My Fair Lady

. Although it was normal not to record an entire score,

it was curious that a musical highlight like “The Embassy Waltz” went unrecorded on the album. Some of the other changes are noted in

table 7.1

.