Legions of Rome (45 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

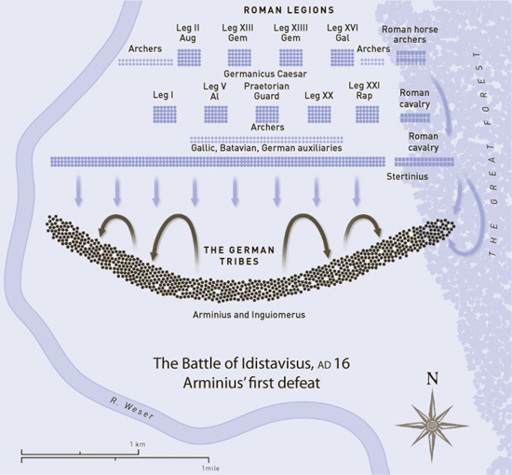

The legionaries stood in their ranks, waiting to meet the German rush, stock still, like statues, the sun glinting on their standards and military decorations, the horsehair plumes on their helmets wafting in the morning breeze. This would be one of the last times that legionaries wore plumes in battle; before long, they would be relegated to parade use only.

One of Germanicus’ aides then pointed to the sky. “Look, Caesar!”

Germanicus looked up. Eight eagles were flying overhead—one for each of Germanicus’ legions. As the Romans watched, the birds dipped toward the forest. Germanicus called to his troops: “Follow the Roman birds, the true deities of our legions!,” then ordered his trumpeter to signal the front line to charge. [Ibid., 17]

With a determined roar, the auxiliaries surged forward. Behind them, a line of foot archers loosed off a looping volley of arrows at the oncoming tribesmen. Soon, Germans and Roman front line were locked together.

Stertinius and the cavalry drove into right flank and rear of the German horde. The impact of this cavalry onslaught drove a mass of Germans away from the trees, where they collided with thousands of other Germans running toward the forest to escape the cavalry attack from the rear. Cheruscans on the hill slopes were forced to give ground by their own panicked countrymen. After his men had charged without

waiting for his orders, Arminius, on horseback, had been forced to join them. In the midst of the fighting, he was soon wounded.

Realizing that the day was already lost, Arminius smeared his face with his own blood to disguise his identity, urged his horse forward, and with his long hair flying, headed toward the Roman left wing, by the trees, which was occupied by Chauci Germans from the North Sea coast. These men had fought alongside Arminius in the Teutoburg, but had since allied themselves with Germanicus. Tacitus was to write: “Some have said that he was recognized by Chauci serving among the Roman auxiliaries, who let him go.” [Ibid.]

Arminius escaped into the forest, and kept riding, as, behind him, Germanicus sent his legions into the fight. The struggle between 128,000 men went on for hours. “From nine in the morning until nightfall the enemy were slaughtered,” said Tacitus, “and ten miles were covered with arms and dead bodies.” Arminius’ army was routed. “It was a great victory, and without bloodshed to us,” Tacitus declared. But Arminius himself was still at large. [Ibid., 18]

AD

16–17

XIV. BATTLE OF THE ANGRIVAR BARRIER

No prisoners, no mercy

After the bloody defeat of Idistavisus, Arminius was determined to have his revenge on Germanicus and his legions. In years past, when the Angrivari tribe was at war with the Cherusci, they had built a massive earth barrier to separate the tribes. The Weser river ran along one side of the Angrivar barrier; marshland extended behind it. A small plain ran from the barrier to forested hills. It was here at the barrier that Arminius planned to defeat Germanicus Caesar.

Word reached Germanicus that Arminius and his allies were regrouping at the barrier and receiving thousands of reinforcements. From a German deserter, Germanicus also learned that Arminius had set another trap for him, hoping to lure the Romans to the barrier. Arminius would be waiting in the forest with cavalry, and would emerge behind Germanicus as he attacked the barrier, to destroy him from the rear. Armed with that intelligence, Germanicus made his own plans. Sending his

cavalry to deal with Arminius in the forest, he advanced on the Angrivar barrier in two columns.

While one Roman column made an obvious frontal attack on the barrier in full view of its thousands of German defenders, Germanicus and the second division made their way unnoticed along the hillsides. He then launched a surprise flanking attack against the Germans. But, in the face of determined defense, and devoid of scaling ladders or siege equipment, Germanicus’ troops were forced to pull back. After bombarding the barrier with his legions’ catapults, keeping the Germans’ heads down, Germanicus personally led the next attack, at the head of the Praetorians, removing his helmet so that no one could mistake who he was. The men of eight legions followed close behind their bareheaded general and the Praetorians. On clambering up the barrier they found a “vast host” of Germans lined up on the far side, commanded by Arminius’ uncle Inguiomerus, who, with blood-curdling war cries, surged forward to repulse the Romans.

The intense hand-to-hand combat continued for hours. Germanicus ordered that no prisoners be taken. The situation was equally perilous for both sides. “Valor was their only hope, victory their only safety,” said Tacitus. “The Germans were equally brave, but they were beaten by the nature of the fighting and the weapons,” for they were too tightly compressed to use their long spears effectively. [Tac.,

A

,

I

, 21]

Pushed into woods, trapped with their backs to the marsh, the tribesmen were slaughtered. At nightfall, the killing stopped. The Germans had been dislodged from the barrier and butchered in their thousands. Inguiomerus escaped, but took no further part in German resistance. That night, Germanicus was joined by Seius Tubero, commander of the Roman cavalry that had gone after Arminius in the forest. Tubero, a close friend of Tiberius, had certainly prevented Arminius from attacking Germanicus in the rear, but after indecisive fighting had allowed the German cavalry to escape. While the battle at the barrier had been another crushing Roman victory, Arminius had again evaded capture.

The Roman victory was soured when, on the return voyage to Holland, a number of Germanicus’ ships were wrecked in a storm. To prove that the legions were still to be reckoned with, Germanicus immediately regrouped his forces and led a new raid across the Rhine, this time returning with another of Varus’ lost eagles.

The Senate heaped honors on Germanicus, and the adoring Roman people sang

the prince’s praises. But Tiberius was unimpressed. When Germanicus asked the emperor for another year to complete the subjugation of the Germans, he recalled him. Germanicus returned to Rome, “though,” said Tacitus, “he saw that this was a pretense, and that he was hurried away through jealousy from the glory he had already acquired.” There would be no further Roman expeditions east of the Rhine during the reign of Tiberius. [Ibid., 26]

After Germanicus celebrated his Triumph in Rome in

AD

17, Tiberius made him supreme Roman commander in the East, and in Syria, in

AD

19, Germanicus, Tiberius’ heir apparent as emperor, would die—apparently poisoned, with Tiberius the chief suspect. Ironically, in Germany that same year, Arminius would also die, and also at the hands of his own people. Many hundreds of years later, Arminius, or Hermann, would become the hero of German nationalists.

As for Germanicus Caesar, many modern-day historians consider him a mediocrity. Yet Germanicus would be lamented by the Roman people for generations—as late as the third century, his birthday was still being commemorated on June 23 each year. [Web.,

RIA

, 6] Fearless soldier and noble prince, Germanicus was, said Cassius Dio in the third century, “the bravest of men against the foe” yet “showed himself most gentle with his countrymen.” [Dio,

LVII

, 18]

AD

17–23

XV. TACFARINAS’ REVOLT

Shame and fame in North Africa

Tacfarinas was a native of Numidia in North Africa who joined the Roman army and served with a Numidian auxiliary unit for a number of years. Sometime before

AD

17 he deserted and led a roving band of robbers, who plagued travelers and outlying farms in southern Tunisia. Like Robin Hood’s merry men, Tacfarinas’ band attracted more and more disaffected locals as its successes mounted. With the addition of auxiliary deserters, it grew to the size of a small army.

By

AD

17, using the skills he had learned in the Roman military, Tacfarinas had formed his men up behind standards in maniples and cohorts, and equipped and trained them like legionaries. That year, he began leading them against Roman outposts

throughout the province of Africa, which was administered from Carthage on the coast. The site of the original Carthage and Roman Carthage is today a residential suburb of Tunis, capital of Tunisia.

This was not the first time that a former Roman auxiliary had used the skills learned from Rome against her, nor would it be the last. Tacfarinas’ little army soon became more than a nuisance to the Roman authorities. The failure of those authorities to halt Tacfarinas’ raids on farms, villages and military outposts attracted many more rebel recruits to his force. The fighting men of Tacfarinas’ own people, the Musulamian tribe from territory bordering the Sahara Desert, willingly joined his ranks, while those of the neighboring Ciniphi tribe were compelled to do so by Tacfarinas.

Dark-skinned Moors from neighboring Morocco also rallied to Tacfarinas; their cavalrymen were famous for riding like the wind without bridles, while their infantry were nimble. The leader of Tacfarinas’ Moorish allies was Mazippa, whom Tacfarinas put in charge of his mobile division, made up of cavalry and light infantry. Tacfarinas himself retained command of the heavy infantry. In total, Tacfarinas now commanded a force of up to 30,000 men. Now, he was no mere bandit leader, he was a general, and his partisan army threatened Rome’s control over North Africa.

To counter Tacfarinas’ army, just a single legion, the 3rd Augusta, was stationed in all of North Africa. Since the beginning of Augustus’ reign, the legion had been based at the city of Ammaedra—Haidra, in modern-day Tunisia. This town was well inland, close to the border with Numidia. The legion, together with the auxiliary

units based in the provinces of North Africa, gave the governor of Africa, the proconsul Furius Camillus, little more than 10,000 troops. While Camillus’ ancestors had gained fame as Roman commanders, Camillus himself, said Tacitus, “was regarded as an inexperienced soldier.” [Tac.,

A

,

II

, 52]

Despite having no record as a field commander, Camillus combined the 3rd Augusta Legion with all his auxiliaries plus troops from Roman allies in the region, and marched against Tacfarinas. Knowing that he significantly outnumbered the Romans, and having trained his men in the Roman style, Tacfarinas possessed the confidence to meet Camillus in open battle rather than rely on the hit-and-run tactics that had previously brought him success. Camillus was not an ambitious man, but he was a loyal servant of Rome and had a steady nerve. [Ibid.] As the two armies formed up on the flat North African landscape, facing each other, Camillus calmly and deliberately allocated his units their places, putting the 3rd Augusta Legion in the center of his battle line and his light infantry and two cavalry squadrons on the wings.

When the battle began, the Africans charged, but the Roman troops held their ground. Camillus drew the Numidians into close combat, after which the 3rd Augusta Legion soon overran Tacfarinas’ inexperienced and over-confident infantry. The victory was swift, and appeared complete. But Tacfarinas escaped the battlefield, and lived to fight another day. Once news of the Camillus’ victory reached Rome, the Senate voted him Triumphal Decorations, which was the next best thing to a Triumph. But the award was a little premature; Tacfarinas was far from conquered.

Gathering fresh support, Tacfarinas began his raiding again the following year, so that, by the autumn of

AD

19, the Palatium decided to take the unusual step of sending an additional legion to the African front to help the province’s new governor. That governor was Lucius Apronius, a personal friend of the emperor; Tacitus actually described him as a sycophant of Tiberius. [Tac.,

A

,

II

, 32]

The legions stationed in Africa and Egypt were generally considered to be inferior to those in Europe, so a “superior” European-based legion was now given the job of going to North Africa to complete the task which the local legionaries had not been able to accomplish. The legion chosen for the job was the 9th Hispana, which had been based in Pannonia ever since taking part in the Pannonian War of

AD

6–9. Led by their senior tribune and second-in-command, Gaius Fulvius, in December

AD

19 the men of the 9th Hispana Legion marched out of their winter quarters at Siscia and tramped to the city of Aquileia in northeastern Italy. From there they proceeded

down to Rimini, on the Adriatic coast, then down the Aemilian Way and finally the Flaminian Way, the military highway to Rome.