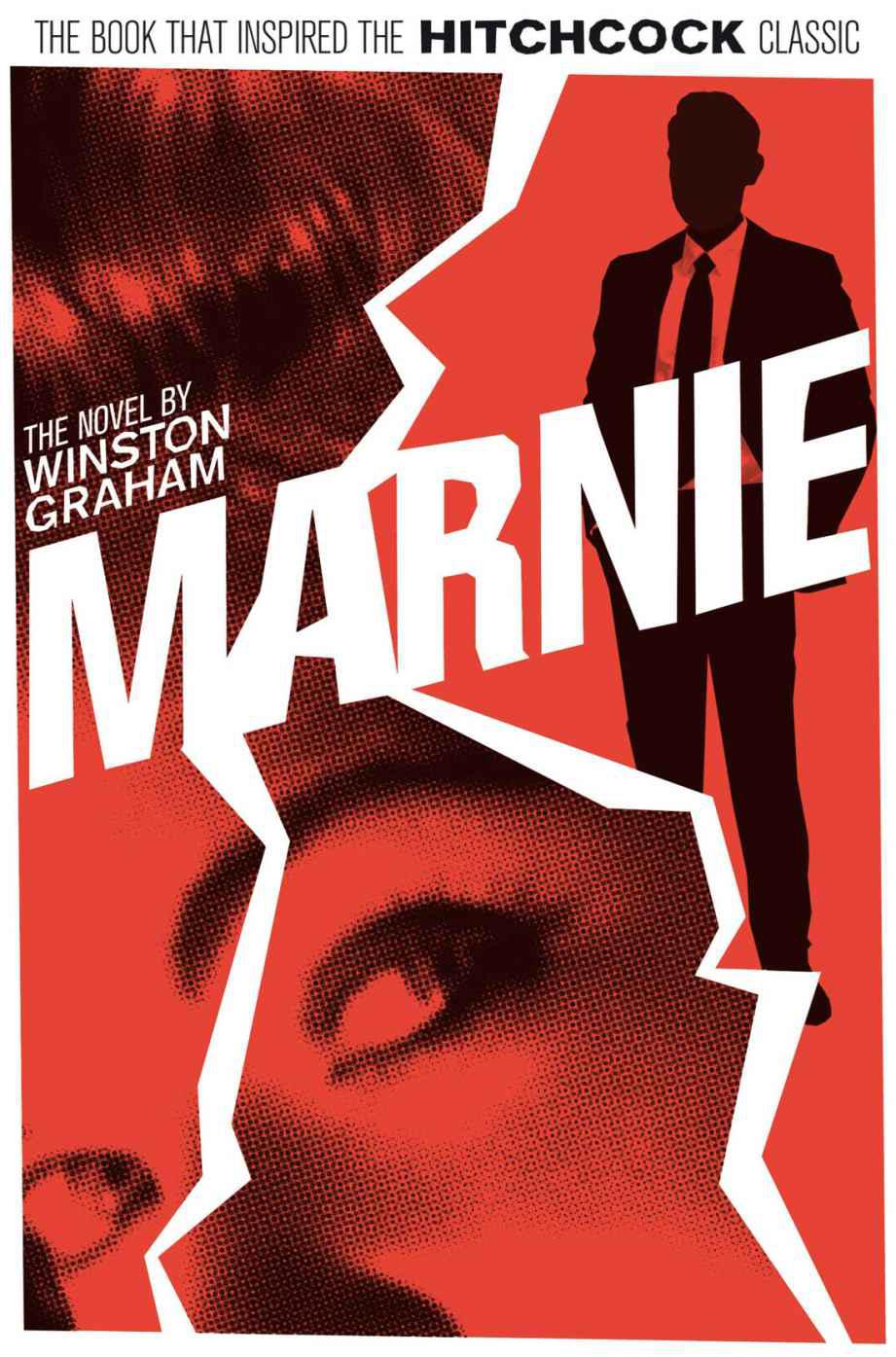

Marnie

Authors: Winston Graham

- Title page

- Author biography

- Contents

- CHAPTER ONE

- CHAPTER TWO

- CHAPTER THREE

- CHAPTER FOUR

- CHAPTER FIVE

- CHAPTER SIX

- CHAPTER SEVEN

- CHAPTER EIGHT

- CHAPTER NINE

- CHAPTER TEN

- CHAPTER ELEVEN

- CHAPTER TWELVE

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN

- CHAPTER FOURTEEN

- CHAPTER FIFTEEN

- CHAPTER SIXTEEN

- CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

- CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

- CHAPTER NINETEEN

- CHAPTER TWENTY

- CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

- CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

- CHAPTER ONE

- Copyright page

CHAPTER ONE

‘Good night, miss,’ said the policeman as I came down the steps, and ‘good night,’ I answered, wondering if he would sound as friendly if he’d

known what was in this attaché case.

But he didn’t, and I took a taxi home. Throwing money away, because you could do it easily by bus, but this was a special day and you had to splash sometimes. I paid the taxi off at the

end of the street and walked down to my two-roomed flat and let myself in. People might think it lonely living on my own nearly all the time, but I never found it lonely. I always had plenty to

think about, and anyway maybe I’m not so good on people.

When I got in I took off my coat and shook out my hair and combed it in front of the mirror; then I poured out a half and half of gin and french as another part of the celebration. While I drank

it I went over a few train times and emptied a couple of small drawers. Then I took a bath, my second that day. Somehow it always helped to wash something out of your system.

While I was still in it the telephone rang. I let it go on for a bit and then climbed out of the warm water and draped a towel round myself and padded into the living-room.

‘Marion?’

‘Yes?’

‘This is Ronnie.’

I might have guessed it. ‘Oh, hello.’

‘Do I detect a lack of enthusiasm in the voice?’

‘Well, it’s a bit inconvenient, dear. I was just in my bath.’

‘What a delicious thought. How I regret this isn’t television!’

Well, I mean, I might have expected that from Ronnie.

‘Are you still set on going away on your own tomorrow?’ he asked.

‘But, Ronnie, I’ve said so at least six times.’

‘You’re a queer girl. Are you meeting another man?’

‘No, of course not. I’ve told you. I’m spending the weekend with this school-friend in Swindon.’

‘Then let me drive you down.’

‘Ronnie, dear, can’t you understand? We don’t want a man. We just want to natter together about old times. I don’t get much opportunity to see her.’

‘They work you too hard at that office. I’ll come and see old Pringle one of these days. But seriously . . .’

My thumb-nail had got caught on the office door and the varnish had chipped. Needed touching up.

‘Seriously what?’

‘Won’t you give me your phone number?’

‘I don’t think she has one. But I’ll try and ring you.’

‘Promise. Tomorrow evening.’

‘I can’t

promise

. I’m not sure where the nearest box is. But I’ll really promise to try.’

‘What time? About nine?’

‘Ronnie, I’m beginning to shiver. And there’s a horrid stain on the carpet all round my feet.’

Even then he clung on like a cadger at a fair, taking as long as he could to say goodbye. When I could get the phone back I was nearly dry and the water had gone cold, so I dusted myself with

talc and began to dress.

Everything I put on was new: brassiere, panties, shoes, nylons, frock. It wasn’t just taking care; it was the way I’d come to like it. I suppose I have a funny mind or something, but

everything has to be just as it should be; and I like it to be that way with people too. That was why the tie-up with Ronnie Oliver was something I’d be glad to be out of. Human beings . . .

well, they just won’t be ticked off, docketed, that’s what’s wrong with them; they spill over and spoil your plans – not because you are out in your estimates but because

they are. Ronnie, of course, thought he was in love with me. Big passion. We’d only met a dozen times because I’d kept on putting him off, saying I’d other dates etc. Anyway it

was the old old story.

My cast-offs were in my case, which would only just shut. You always seem to hoard up stuff even in a few months.

I went round the flat. I started in the kitchenette and went over it inch by inch. The only thing I saw in it was a cheap tea towel I’d bought just after Christmas, but I grabbed that and

packed it with the rest. Then I went through the bathroom and lastly the bed-sitting-room.

I always reminded myself of the coat I’d left behind in Newcastle last year. Remembering that kept me on the alert; your eyes get to see something as part of the background and then

you’ve left something behind and that’s too bad because you can’t come back for it.

I took down the calendar and packed that. Then I put on my coat and hat, picked up the suitcase and the attaché case and let myself out.

They were glad to see me at the Old Crown at Cirencester. ‘Why, Miss Elmer, it’s three months since you were here last, isn’t it? Are you going to stay long

this time? Yes, you can have your usual room. It’s not been good hunting weather this month; but of course you don’t hunt, do you; I’ll have your cases sent up directly. Would you

like some tea?’

I always grew an inch staying at the Old Crown. Often enough I got by as a lady nowadays – funny how easy it was; but this was nearly the only place where I could believe it myself. The

chintzy bedroom looking on the courtyard, with this four-poster bed and the same servants, they never changed, they were part of the furniture, and every day out to Garrod’s Farm to pick up

Forio and ride for hours on end, stopping at some little pub for lunch and coming home in the failing light. It was life; and this time instead of staying two weeks I stayed four.

I didn’t read the papers. Sometimes I thought of Crombie & Strutt, but in an idle sort of way as if working for them was something that had been done by another person. That always

helped. Now and then I wondered how Mr Pringle would take it and if Ronnie Oliver was still waiting for his telephone call, but I didn’t lose any sleep over it.

At the end of four weeks I went home for a couple of days, but said it was a flying visit and left on the Saturday. I dropped most of my personal things at the Old Crown and spent the night at

Bath at the Fernley, signing in as Enid Thompson, last address the Grand Hotel, Swansea. In the morning I bought a new suitcase, a new spring outfit; then I had my hair tinted at one of the stores.

When I came out I bought a pair of plain-glass spectacles, but I didn’t put them on yet. When I got to the station that afternoon I took out of the left-luggage office the attaché case

I’d left there nearly five weeks ago, and there was room for it inside the new suitcase I’d bought that morning. I bought a second-class ticket for Manchester – which seemed as

good a place as anywhere, as I had never lived there – and a

Times

, which I thought might help me in picking out a new name.

Names are important. They have to be neither too ordinary nor too queer, just a name, like a face, that’ll go along with the crowd. And I’d found from experience that the Christian

name had to be like my own, which is Margaret – or usually Marnie – because otherwise I might not answer to it when called, and that can be awkward.

In the end I chose Mollie Jeffrey.

So at the end of March a Miss Jeffrey took rooms in Wilbraham Road and began to look for a job. I suppose you’d have seen her as a quiet girl, quietly dressed, with fair hair cut short

round the head and horn-tipped spectacles. She wore frocks that were a bit too big for her and a bit too long. It was the best way she knew of looking slightly dowdy and of making her figure not

noticed – because if she dressed properly men looked at her.

She got a job as usherette at the Gaumont Cinema in Oxford Street, and kept it until June. She was friendly enough with the other usherettes, but when they asked her to go places with them she

made excuses. She looked after her invalid mother, she said. I expect they said to each other: poor object, she’s one of those, and what a pity; you’re only young once.

If they only knew it, I couldn’t have agreed with them more. We only had different ideas what to do about it. Their idea was fooling around with long-faced pimply men, ice skating or

jiving on their days off, two weeks at Blackpool or Rhyl, queuing for the Sales, Pop discs, and maybe hooking a man at the end of it, some clerk in an export office, then babies in a council house

and pushing a pram with the other wives among the red-brick shops. Well, all right, I’m not saying they shouldn’t, if that’s what they want. Only I never did want that.

One day I tried for a job at the Roxy Cinema, close by the Gaumont, where they wanted an assistant in the box office. The manager of the Gaumont gave me a good reference and I got the job.

When I’d been there three months the staff arrangements worked out that I was due for a week’s holiday, so for the first day or two I went home.

My mother lived in Lime Avenue, Torquay. It’s one of a row of Victorian houses behind Belgrave Road, and it’s easy for the shops and the sea front and the Pavilion.

We had moved there from Plymouth about two and a half years ago, and we’d been lucky to get a house unfurnished. My mother was a cripple, or at least she got about fairly well but she’d

had something wrong with one leg for about sixteen years. She always said she was the widow of a naval officer who was killed in the war, but in fact Dad hadn’t ever got further than Leading

Seaman when he was torpedoed. She also said she was a clergyman’s daughter, and that wasn’t true either, but I think Grandfather was a Lay Preacher, which is much the same thing, only

you don’t lose your amateur status.

Mother was fifty-six at this time, and living with her was a woman called Lucy Nye, a small, moth-eaten, untidy, dog-eared, superstitious, kindly creature with one eye bigger than the other. One

thing I’ll always say for Mother, you never saw her anything but carefully and properly got up. She always had a sense of what was right and proper and she lived for it. When I got in that

day she was sitting in the front window watching, and as soon as I rapped on the door she was there, stick and all.

She was an odd person – she really was – I got to realize it more as I grew older – and even though she kissed me and even though I knew I was the apple of her eye – God

help me – I could still tell there was a sort of

reserve

in the welcome. She didn’t let up, and even while she kissed you she kept you just that bit at a distance. You knew

she’d been waiting at that window for hours to see you come down the street, but you wouldn’t be popular if you let on.

She was a thin woman; I always remember her as extremely thin. Not like me because although I’m quite slight I’m well covered. I don’t think she’d been like that even at

twenty-two. She had a really good bone structure, like old pictures of Marlene Dietrich, but she’d never had enough flesh to cover it, and as she got older she got haggard.

That was the hard thing of living away from home. I should never have thought of her as haggard, not that word, if I’d stayed with her; it was going away and coming back that forced you to

see things with new eyes. She was in a new black tailormade today.