Legions of Rome (43 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

“They succeeded in getting past the foes’ first and second outposts,” said Dio. But by the time they reached the third and last outpost, the column was well strung out, and the civilians, cold, exhausted and afraid, had lost contact with the soldiers leading the way. Women and children panicked, and began calling out to the troops to come back for them—calls which the German sentries heard in the night. [Ibid.]

Caedicius and his troops now had to fight their way through the alerted enemy. They cut down the first Germans they encountered, but tribesmen were coming from everywhere behind them. Caedicius had to think fast. He ordered the civilians to drop what they were carrying and run for it. At the same time, he sent his trumpeters ahead and had them sound the signal for his troops to hurry forward at a double-quick march. The Germans, already distracted by the plunder they found discarded by the civilians, thought the trumpets were being sounded by Roman relief units sent by Asprenas, and gave up the pursuit. Some civilians were killed or captured by the Germans, but “the most hardy” managed to escape, [Ibid.] as did Caedicius and his men, who “with the sword won their way back to their friends.” [Velle.,

II, CXX

]

At Vetera, Asprenas, learning that Roman fugitives were making their way toward the Rhine, sent troops across to their assistance, and Caedicius and his party accordingly reached the safety of the western bank of the Rhine. [Dio,

LVI

, 22] Behind them, the Germans destroyed Fort Aliso. This was the final act of Arminius’ uprising. It had achieved its objective—there was no longer a Roman military presence east of the Rhine.

AD

9

THE REACTION AT ROME

Panic and grief

The emperor Augustus was devastated by the news of what became known as the Varus disaster when he heard of it in October

AD

9. He let his hair grow and failed to shave for months, mourning the lost legions as if they were his children. Suetonius says that he was often heard to cry, “Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!” [Suet.,

II

, 23] Eighteenth-century historian Edward Gibbon was to remark: “Augustus did not receive the melancholy news with all the temper and firmness that might have been expected from his character.” [Gibb., n. I, 1.3]

The immediate dread in Rome was that Arminius and his Germans would flood over the Rhine, sweep down through Gaul, and ravage Italy. Suetonius says the emperor immediately ordered patrols of the city at night to prevent any rising of the populace. He also prolonged the terms of all his provincial governors, so that Rome’s allies would have men they knew and trusted in places of power. And, suddenly mistrusting Germans, he temporarily disbanded his bodyguard, the German Guard. [Suet.,

II

, 23; 49]

Augustus also ordered special cohorts of slaves levied at Rome, and sent them to Germany. “The Roman bank of the Rhine had to be held in force.” Recruited as slaves from the households of well-to-do men and women, these men were officially given their freedom once they joined their cohorts. These special units of freedmen were euphemistically called “Volunteer” cohorts, because the slave owners were forced to volunteer their services. On Augustus’ express orders, the members of these special units were not permitted “to associate with soldiers of free birth or to carry arms of standard pattern.” [Ibid., 25]

As these Volunteer cohorts marched to the Rhine, six of the legions and numerous auxiliary units that had been fighting in Dalmatia, where the Pannonian War had ended just five days before the Varus disaster in Germany, were heading in the same direction. But under no circumstances would Augustus permit his legions to cross the Rhine. The river was now the empire’s borderline.

Augustus did not raise new legion enlistments to replace the Teutoburg dead. He retired the shamed numbers of the destroyed legions, the 17th, 18th and 19th, and

left the Roman army numbering twenty-five legions. The Varus disaster was a stinging blow to Roman pride that ranked with Marcus Crassus’ 53

BC

defeat at Carrhae. The September day in

AD

9 that General Varus’ three legions ceased to exist would never be forgotten by Romans. It was as if the defeat, and the loss of the sacred eagles of the legions, scarred the national soul.

At Vetera, a stone monument 54 inches (137 centimeters) high was raised to Centurion Marcus Caelius of the 18th Legion by his brother. The monument, which survives to this day, shows Caelius, looking fierce, adorned with all his military decorations and holding his centurion’s vine stick, the symbol of his authority. On either side of Caelius are his two servants, Privatus and Thiaminus. Both carry Caelius’ name, indicating that they had become freedmen. In all probability they too perished at the Teutoburg, with thousands of other civilians in Varus’ train.

The monument’s inscription, after giving the details of the centurion’s life, asked that, should Marcus Caelius’ bones ever be found, they be deposited there, at the monument. But Caelius’ whitening bones lay across the Rhine, on a silent, deserted battlefield in the Teutoburg Forest, indistinguishable from those of thousands of his fellow soldiers who had also been left to rot by the victors of the battle. Caelius’ monument and his bones would never be united.

AD

14–15

XI. INVADING GERMANY

Germanicus versus Arminius

Ever since the disaster in the Teutoburg Forest, Romans had thirsted for revenge—for the loss of Varus’ three legions, for the loss of Rome’s foothold east of the Rhine, and for the loss of Roman prestige which the defeat by Arminius and the German tribes had represented. In

AD

14, almost by accident, the Roman military was given the excuse and the opportunity to take that revenge.

Augustus, who had refused to send anymore military expeditions across the Rhine following the Varus disaster, died in August

AD

14, after reigning since 30

BC

. Several years before, Augustus had extended the enlistments of all legionaries from sixteen to twenty years. In the atmosphere of uncertainty that followed the emperor’s death, with his stepson Tiberius not immediately claiming the throne, the extended enlistments and numerous other complaints about service conditions sparked discontent that spread through the legions and ignited the mutinies. In the wake of

Augustus’ death, mutinies broke out among the three legions stationed in Dalmatia and the eight legions on the Rhine.

The Dalmatian legions were soon brought to heel by Tiberius’ son Drusus and Praetorian prefect Sejanus, who led elements of the Praetorian Guard and German Guard to Dalmatia where they executed ringleaders. In command on the Rhine was Drusus’ dashing 28-year-old adoptive brother Germanicus Caesar, brother of Claudius, father of Caligula, and the grandfather of Nero. He himself was heir apparent to the Roman throne. Germanicus was collecting taxes in Gaul when his legions mutinied. Hurrying first to the army of the Lower Rhine at the city that became Cologne, he settled their grievances, then did the same with the army of the Upper Rhine at Mogontiacum (Mainz). But when discontent flared again at Mogontiacum, Germanicus’ general Aulus Caecina had loyal legionaries cut the troublemakers to pieces. “This was destruction rather than remedy,” Germanicus lamented. So, to distract his troops, he launched a lightning campaign east of the Rhine. [Tac.,

A

,

I

, 49]

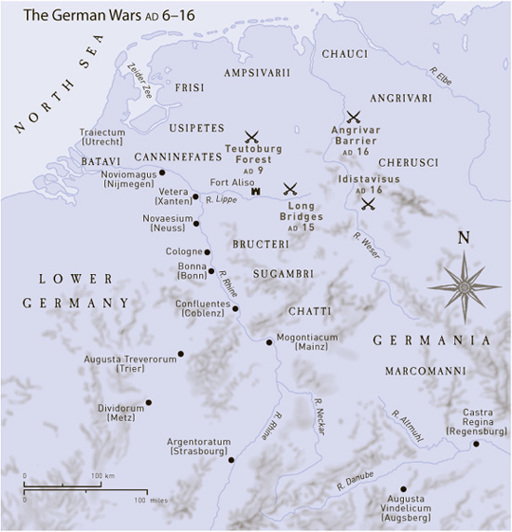

In October, Germanicus led 12,000 men from four legions, twenty-six allied cohorts, and eight wings of cavalry into the territory of the Marsi, between the Lippe and Ruhr rivers. Surprising and wiping out Marsi warriors while they were celebrating their festival of their goddess Tamfana, Germanicus advanced across a broad front for 50 miles (80 kilometers), destroying every village and every living thing in his path. As he turned his army around and marched back toward the Rhine, Germans from the Bructeri, the Tubantes, and the Usipetes tribes overtook him, but were beaten off the Roman column’s tail by the 20th Legion, acting as rearguard. A day later, the column crossed back to the western side of the Rhine. The Senate voted Germanicus a Triumph for his success. But he had only just begun.

During the winter of

AD

14/15, all eight of Germanicus’ Rhine legions prepared for a massive spring offensive in Germany. But when news reached Germanicus that Arminius was clashing with his father-in-law Segestes, king of the Chatti tribe, he seized the opportunity to split the German confederation by striking before the winter had ended. From Mogontiacum, Germanicus led the four AUR (Army of the Upper Rhine) legions and their auxiliary support across the river and into the Chatti homeland. At the same time, Caecina led his four legions of the Lower Rhine army across the Rhine at Vetera, via a bridge of boats.

With this offensive taking the Germans completely by surprise, Germanicus made a rapid advance as far as the River Eder. After burning Mattium, the Chatti capital,

he turned for the Rhine. Caecina’s army covered his withdrawal, colliding with the Cherusci and Marsi tribes, who hurried down from the north in support of the Chatti.

As Germanicus withdrew, his aid was sought by the son of the Chatti king. Segestes wanted to return to the Roman fold, and offered Thusnelda, his daughter and the pregnant wife of Arminius, as prize. But Segestes was surrounded and besieged by Arminius’ Cheruscans at a stronghold in the hills. Germanicus marched to the stronghold and drove off the Cherusci, then was able to return to the western side of

the Rhine with the king of the Chatti and Arminius’ wife. Thusnelda was sent to Italy and confined at Ravenna. (Her sister-in-law, the Chattian wife of Arminius’ brother Flavus, also lived at Ravenna, with her son Italicus.)

Not content with this success, Germanicus launched a full-scale offensive in the summer, involving a three-pronged attack. In the first stage, Germanicus took a fleet of ships from Traiectum, today’s Utrecht in Holland, across the Zeider Zee and into the North Sea. He then sailed along the Frisian coast, turning up the River Ems, the Roman Amisia, retracing a route followed by his father Drusus Caesar in 12

BC

and Tiberius in

AD

5. Meanwhile, Albinovanus Pedo led a diversionary cavalry operation in the Frisian area of Holland and northwest Germany. At the same time, Caecina crossed the Rhine from Vetera yet again, then marched his four army of the Lower Rhine legions northeast, heading for the Ems. All three forces linked up beside the river; Germanicus had brought together close to 80,000 men deep inside German territory.

From here, Germanicus sent Lucius Stertinius with 4,000 cavalry to sweep through the homeland of the Bructeri, routing every German band that stood in their path. In one village, Stertinius’ troopers recovered the sacred golden eagle of the 19th Legion taken by the Bructeri during the Teutoburg massacre. At the same time, Germanicus marched the legions to the Teutoburg Forest, site of the Varus disaster, where they found, lying on the ground, the whitening bones of thousands of Roman legionaries. Skulls were nailed to tree trunks. They found the pits where Roman prisoners had been temporarily held, and, in adjacent groves, altars where the junior tribunes and first-rank centurions had been burned alive as offerings to the German gods. There, “in grief and anger,” Germanicus’ men buried the bones of Varus’ legionaries, with “not a soldier knowing whether he was interring the remains of a relative or a stranger.” [Tac.,

A

,

I

, 62]

Germanicus’ legions marched on, linking up with Stertinius and the cavalry and dispersing harassing German bands. On the bank of the Lippe, Germanicus rebuilt Fort Aliso, possibly because it was there that his father had died, and garrisoned it with auxiliaries. On reaching the Ems, Germanicus and the Upper Rhine legions boarded the waiting fleet, and Pedo’s cavalry set off to retrace their path via the Frisian coast. Caecina turned for the Rhine with the 1st, 5th Alaudae, 20th and 21st Rapax legions. On Germanicus’ orders, Caecina was to follow a long-neglected overland route to the Rhine. It was called Long Bridges.

AD

15

XII. BATTLE OF LONG BRIDGES

How the 1st Germanica Legion made its name

As the summer of

AD

15 ebbed away, Germanicus Caesar was withdrawing his Roman army from Germany after a successful campaign. While Germanicus’ division was returning to Holland by sea, and Albinovanus Pedo was leading the cavalry back via Frisia, Aulus Caecina, commanding general of the Army of the Upper Rhine, was leading the 1st, 5th Alaudae, 20th and 21st Rapax legions along the route called Pontem Longus, or Long Bridges.

This causeway had been built through a marshy valley by Lucius Domitius during his campaigns in Germany between 7

BC

and

AD

1. Long Bridges provided the shortest route to the Rhine, but Germanicus knew this road was narrow and frequently flanked by muddy quagmires, making it an ideal place for an ambush, so in sending Caecina this way he had urged his deputy to make all speed through the region.