Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (43 page)

Read Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan Online

Authors: James Maguire

Ed discouraged him, fearing the reaction to talk of mental illness, and Logan conceded. But during the broadcast, Sullivan came across Logan backstage looking despondent. The showman asked the director if he still wanted to tell his personal story, and Logan said yes. “

Ed was terrified of CBS’s reaction,” Logan recalled. “But he took a chance with me.” Ed abruptly changed the show’s running order to allow time for Logan’s speech. The director went onstage and described, in very personal terms, the history of his mental breakdown, hospitalization, and subsequent recovery. He urged people to view mental illness as a disease that could be treated, not a moral failing. When he stopped speaking, the studio sat in stunned silence—and then broke into a torrent of applause. CBS received a small mountain of appreciative letters.

Ed himself received a letter from a judge on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, Justice Michael A. Musmanno (well-known for presiding over the Nuremberg trials), who wrote to say that seeing Josh Logan speak on

Toast of the Town

influenced one of his recent court decisions. A local woman had been briefly confined in a mental institution, after which she experienced a full recovery. But during her stay her husband took permanent custody of their children, which she contested in court. Justice Musmanno ruled, in part based on Logan’s story of overcoming mental illness, that confinement in a mental institution does not nullify a parent’s rights if that individual can medically certify his or her recovery.

At a later date, Ed recounted the Logan story while speaking to a civic organization in Oklahoma (he accepted countless such invitations). After his talk, the director of a mental health program told Sullivan that the day after Logan’s appearance, his state budget director increased his appropriation due to the star’s emotional appeal. Such was the power of this new medium. In the late 1960s, Ed pointed to the Logan episode as one of the show’s peak moments.

Comedy Hour

still led

Toast of the Town

in overall ratings during the 1952–53 season, yet the balance was starting to shift. While in the fall of 1951 the average Trendex rating for

Comedy Hour

topped that of

Toast of the Town

by a comfortable margin, 32.6 to 21.9, by the spring of 1953 that margin had narrowed to 31.3 to 24.7.

Comedy Hour

’s slip was small, yet that slippage revealed a larger trend. Eddie Cantor suffered a heart attack after a 1952

Comedy Hour

performance, and the following season the sixty-one-year-old declared he would quit. The program’s younger hosts were feeling the strain as well. By the 1953–54 season,

Comedy Hour

’s annual budget ballooned to $6 million. In return, Colgate-Palmolive wanted only the biggest names to host. But the top tier, notably Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin—now making $1,000,000 a year from the program—were hard-pressed to keep their routines fresh during months of broadcasts. They weren’t alone. A man in Long Island, New York, after yet another Abbot and Costello

Comedy Hour

without new material, shot his television set. (The resultant publicity earned him an appearance on the game show

Strike It Rich

, where he won a new set.) What had once glittered now began to appear lackluster.

The trend was clear as the 1953–54 season concluded.

Comedy Hour

’s elephantine budget no longer guaranteed it Sunday night dominance. Under pressure from Sullivan, and suffering from creative exhaustion, the show’s ratings were headed inexorably downward. Although

Comedy Hour

held the lead over

Toast of the Town

in the fall of 1953, by the spring of 1954 the two shows’ ratings were running a dead heat. And, as always,

Toast of the Town

’s Nielsens pulled far ahead in the summer, as Ed continued to produce fresh shows while

Comedy Hour

ran reruns. If nothing else, he would outwork his NBC competitor.

One Sullivan maneuver that season was especially revealing of how Ed chipped away at

Comedy Hour

’s ratings. In the fall of 1953, CBS show host Arthur Godfrey was one of the country’s most beloved broadcasters. Some forty million people listened to his morning radio program, and two of television’s top ten shows were his:

Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts

was the third-ranked show, behind only

I Love Lucy

and

Dragnet

; and

Arthur Godfrey and Friends

was the seventh-ranked show, right behind

The Bob Hope Show

and the

The Buick-Berle Show.

With his butterscotch voice and easygoing charm, Godfrey was responsible for twelve percent of CBS’s annual revenues. He delivered his own ads in a folksy, intimate style, refusing to stick to the copy, talking to viewers like old friends—when he chatted about Lipton Tea, listeners felt he sipped it every day.

Godfrey used an ensemble format, in which a regular troupe of clean-cut young singers interacted week after week. For the audience, he and his performers became a surrogate family. Godfrey played the genial uncle as his viewers, largely female, bonded with each of the personalities. So on October 19, 1953, when Godfrey summarily fired one of his singers

during a show

, millions of his fans were shocked, even horrified. Dismissed was Julius La Rosa, a cherub-faced ingénue whose vocal talents were modest, but who inspired fierce matronly love in fans. Right after La Rosa finished crooning a song, Godfrey informed viewers, “

That was Julius’ swan song with us.” Afternoon newspapers blared the news in headlines across the country.

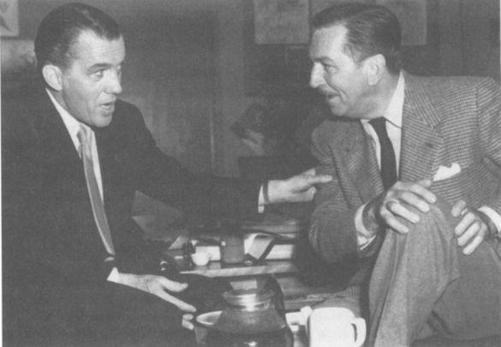

With Walt Disney in the early 1950s. Sullivan’s tribute show to Disney in 1953 helped him compete with the heavily financed The Colgate Comedy Hour, but years later the two men would vie for ratings in the same Sunday night time slot. (Globe Photos)

As the news coverage snowballed, the reason for the firing was clouded in confusion. Godfrey claimed that La Rosa wanted to be released from his contract; rather than announce this in a press conference, he explained, the host decided to tell viewers on the air. La Rosa disputed this, and Godfrey, in a move he soon regretted, explained that the singer had “lost his humility,” and so needed to be fired. La Rosa conceded that he had lost his sweet deference; at age twenty-three he was getting six thousand fan letters a week and fielding constant offers from record labels. Nevertheless, fans were dismayed to learn that Godfrey had fired someone because he couldn’t stand another star in his stable—was there a controlling egoist under that vanilla charm? The day after Godfrey’s remark about “humility,” the word appeared in numerous national headlines, and comedians soon began using it for laughs. The incident even generated its own moniker, as commentators dubbed it the La Rosa Affair. To date, this was the biggest news story in television.

For Ed the story offered an obvious opportunity. He immediately called La Rosa and invited him to his Delmonico apartment. Heartbroken over being fired, the singer came with his lawyer and his priest in tow. Ed offered him $5,000 per show for a series of guest appearances on

Toast of the Town

, which La Rosa gladly accepted. Marlo professed amazement at the amount Ed offered the young singer. “

He’ll be worth it,” Ed said, “Just wait and see.”

He was right. La Rosa’s appearance on October 25, within the week of his firing on Godfrey, was Sullivan’s highest-rated show since his 1948 debut, earning a jaw-dropping

76.6 Trendex rating. Its viewership dwarfed that evening’s

Comedy Hour

starring Lauren Bacall, and even topped the season’s highest rated Jerry Lewis–Dean Martin show. Ed kept exploiting the La Rosa controversy over the next several weeks. The November 29 episode of

Toast of the Town

would undoubtedly have run a distant second to

Comedy Hour

without the publicity sparked by Ed’s booking of La Rosa. That night

Comedy Hour

was hosted by Eddie Cantor, with guest stars Frank Sinatra and Eddie Fisher; Fisher had just been offered the unheard of sum of $1 million by Coca Cola to be their national spokesman. Ed’s lineup that evening reflected his smaller budget: La Rosa; Dr. Ralph Bunche, a black Harvard professor and civil rights activist, winner of the 1950 Nobel Prize; Sophie Tucker, a popular vaudevillian now in late career; Sam Levenson, a young comic still on his way up; Joe E. Lewis, an aging cabaret comic; the AU-American college football players; and The Harmonicats, a mouth-organ trio whose 1947 hit “Peg O’ My Heart” sold 1.4 million copies. It was a solid lineup, but it paled by comparison to the Sinatra-Fisher—Cantor triumvirate. Yet that night’s

Toast of the Town

earned a 54.8 Trendex rating, clearly besting

Comedy Hour

’s 40.1.

Ed’s adept use of the controversy displayed once again how he used his newsman’s nose for current events to turn a small budget into a ratings winner. He kept it up by booking a raft of former Godfrey regulars, like Pat Boone and the McGuire Sisters—performers who hadn’t reached their later popularity but whose status as Godfrey alumni boosted ratings. CBS was uneasy about Sullivan’s continued one-upping of Godfrey; it was a skirmish between two of the network’s top-rated shows. But Ed rebuffed suggestions by CBS executive Hubbell Robinson that he stop. With the ratings it produced he saw it as a natural strategy. “

There’s nothing personal in it,” Ed explained. “If Arthur were fired, I’d hire him.”

One other incident with Godfrey revealed a side of Ed rarely glimpsed by the public. When Godfrey was hospitalized after hip surgery, Sullivan guest hosted his show. The camera captured a man never before seen on television. He danced and sang a tune with the Little Godfreys, accompanied two singers on the zither, warbled a duet with Frank Parker, then topped it off with a soft-shoe routine. It was all light-hearted fun. A reviewer from

Variety

was aghast: “

Why Sullivan can come in strange surroundings and enjoy himself and yet appear so uncomfortable on his very own show is something of an unknown. It’s to be hoped that some of the gold dust carries over from that Wednesday night to Sundays.”

It didn’t. On his own show the effort was too important, too much of a high-stakes struggle, for him to enjoy himself. The self he displayed on the Godfrey show was closer to his Broadway columnist persona, capable of clowning around, comfortable with spontaneity and humor. But that side of Sullivan was stowed backstage when he hosted

Toast of the Town.

He attempted to explain this in the preface to a 1951 book called

The TV Jeebies

, a slender volume that described the new medium’s countless pratfalls:

“People often ask me why I don’t smile more when I face the cameras on ‘

Toast of the Town

.’ In television, unlike any other visual medium, a performer gets only one chance. There are no retakes. He either does it right the first time or the sponsor sees to it that the performer forever holds his peace.… There are literally thousands of tubes, resistors, condensers, and other strange devices in the maze of technical equipment that must not fail. Even the performers can bring on a bad attack of the TV Jeebies with their strapless gown slipping their moorings, ad-libbed jokes that are a bit too salty for television, acts that run over their allotted time and a hundred others things that just couldn’t happen but sometimes do.… In television you get just one chance.”