Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (20 page)

Read Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan Online

Authors: James Maguire

To further investigate New York beauty, he assembled an “All-American, All-Gal Eleven,” a mock all-star football team of female performers:

“Picking the first team, my All-American, All-Gal Eleven, was no part of a cinch … I spent a small fortune taking out each of the candidates, feeding ’em, and noting their reactions.

“In the course of my selections, I had to drop at least twenty girls for one reason or another. I had Peggy Joyce lined up for quarterback, but when she insisted on magnums of champagne for the training table I had to let her go. Claire Carter was ideal for tackle and she would have added blonde charm to the forward wall, but she wouldn’t leave Jay C. Flippen for practice.”

Not all of the women were picked because they were an eyeful. Gracie Allen, who played a ditzy counterpart to George Burns’ straight man, was chosen as quarterback for her ability to confuse the defense. Aunt Jemima, a heavyset vaudeville singer later memorialized as the advertising icon for a pancake syrup, was selected for her heft.

A few weeks later, Ed assembled a corresponding men’s Broadway all-star team, but he gave it short shrift by comparison, and apparently felt it unnecessary to take each man to dinner.

In the fall of 1933, Ed’s high profile as a

Daily News

columnist led to a series of invitations to produce and host charity shows. In November he organized and emceed an all-black show for the Urban League benefit at Manhattan’s Town Hall, presenting tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, singing quartet the Southernaires, and the Nicholas Brothers, a two-brother vaudeville tap dance team. The following evening he emceed a revue he produced for the Jewish Philanthropic Societies, held at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel, featuring a raft of radio and stage stars.

At the end of November he walked onstage for an event that would mark the beginning of a life-long career: his first variety show.

The manager of Manhattan’s Paramount Theatre, Boris Morros, invited him to produce and host the show. The phone call from Morros became a favorite anecdote

of Ed’s, though it appears to be an exaggeration. Morros called Sullivan to offer him $1,000 for a one-week run; for this fee, Ed would choose and pay the performers, taking the remaining money for himself. Ed—overjoyed by the lucrative offer—said, “

You must be crazy.” In Sullivan’s telling, Morros thought the columnist was negotiating and so quickly raised the offer to $1,500. They went back and forth like this, and by the end of the day Morros agreed to pay him $3,750, according to Sullivan. It’s highly unlikely that a theater manager in the depth of the Depression would almost quadruple his offer based on a simple misunderstanding. But the anecdote portrays Ed as highly sought after, and he loved to repeat it. Whatever the actual negotiation process, he readily agreed.

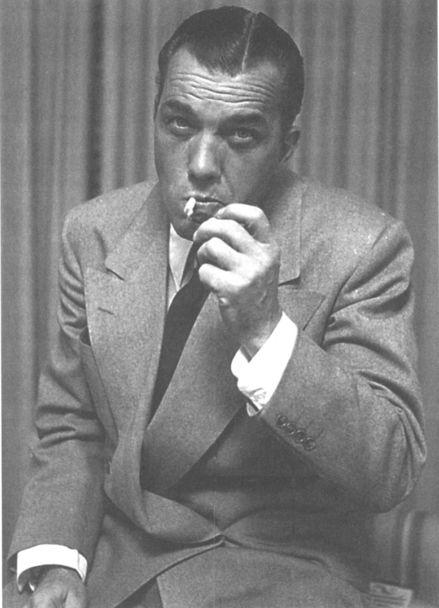

Broadway tough guy: although he would later present himself as the staid guardian of the American living room, Sullivan came of age in the rough-and-tumble of the 1920s New York newspaper business. This 1954 photo reveals the streetwise side of the showman. (Globe Photos)

To organize the show, he relied on a format with a rich tradition: vaudeville. By the early 1930s classic vaudeville was on its last legs. The Depression meant there were fewer people with an extra dime, and movies and radio were offering overwhelming competition. After the first talkie in 1927 the allure of moving pictures had proven irresistible, and radio brought theater into listeners’ homes for free. As Ed had written in 1932,

“No longer does an actor boast of playing ten weeks at the Palace … Now they’re interested only in how many stations they’re on.” Vaudeville had grown stale and dated as many veteran acts offered the same routine year after

year. Yet the American taste for the new and different had continued apace, the Depression notwithstanding. Forward-looking social commentators in the early 1930s were writing nostalgic eulogies for vaudeville.

Although vaudeville circuits were closing, the form’s guiding principles would live on; its roots ran too deep to disappear. Borne of the English music hall, Yiddish theater, and the traveling minstrel show, vaudeville had come into its own in America in the 1880s and had flourished for decades. Several generations of American performers grew up on its stage, including Bob Hope, Jack Benny, Al Jolson, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, W.C. Fields, Mae West, Will Rogers, Ethel Waters, Jimmy Cagney, Bessie Smith, Bums and Allen, Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Sammy Davis, Jr., and the Marx Brothers.

Ethnic distinctions were very pronounced in vaudeville. Irish, Italian, and Jewish performers played their routines according to the broad stereotypes associated with these groups. Present in almost all shows was a blackface act, typically a white performer whose face was blackened with burned cork, affecting a dialect and playing the role of a happy-go-lucky shiftless black man for laughs. The crude caricature of blackface routines was a facet of vaudeville that appeared most dated by the 1930s.

A vaudeville show moved at a relentless tempo, with a blink-and-you-miss-it succession of one-legged tap dancers, comics, ventriloquists, blackface song and dance acts, legitimate musical theater, jugglers, acrobats, and one-liner artists, all pushed along by a master of ceremonies who kept things moving—briskly, at all times. If you didn’t like a routine there was no time to get bored; you’d soon see a new one.

If people enjoyed watching it, an act usually found its way to vaudeville. The Mayo Brothers did a two-man dance-acrobatics routine on a small tabletop. One popular performer was a skilled regurgitator who swallowed live fish and brought them back up at will. Jack Spoons lifted chairs with his teeth while he played the spoons, and Joe Frisco smoked a cigar while doing soft-shoe. Lady Alice balanced trained rats on both arms, with a rodent on top of her head that was trained to blow into a kazoo. Fuzzy Night and his Little Piano featured a man who danced with his piano.

The audience felt that their 10-cent ticket gave them the right to participate as much as the performers. The hecklers and “gallery gods,” as vocal audience members were known, voiced their opinion with full-throated freedom, letting fly with a thin shower of coins or last week’s leftover produce. If the jeers of the gallery gods pronounced an act unworthy, a large hook pulled the performer offstage.

Vaudeville’s core principle was offering something for everyone. The businessmen who ran the major circuits, most notably Benjamin Keith and Edward Albee, knew that an all-inclusive philosophy drew the biggest audience. A single show might offer the likes of Mae West making the men roar with pleasure at her risqué “shimmy” dances; a well-muscled and shirtless Man of Steel providing male pulchritude for the ladies; for recent émigrés, Benny Rubin telling funny stories in Yiddish dialect and Maggie Cline, the “Irish Queen,” belting out

Throw Him Down, McCloskey

; the Nicholas Brothers, two young black boys in elegant suits, dancing a dazzling tap routine; and Poodles Hanneford playing the slapstick clown. Vaudeville was the great wellspring of American entertainment, the heterogeneous offering of every voice. All of its acts existed side by side in a show business melting pot, exposing all the audience members to the dissimilar tastes of their seatmates. The performers, too, experienced cross-cultural pollination, as acts reached across ethnic divisions to steal the comic or musical inventions of their competitors.

Something for everyone, and everyone was invited: the credo of the Keith–Albee circuit was family entertainment. Vaudeville houses had been bawdy places, but under Keith and Albee’s iron-fisted control the shows were cleaned up. It was good for business. The use of vulgarity onstage was strictly prohibited under threat of instant dismissal. Benjamin Keith once advertised that he employed a Sunday school teacher at rehearsals to ensure propriety—though vaudeville shows were earthier than that suggests. But certainly the whole family could attend, kids and all.

Part of vaudeville’s “something for everyone” formula was appealing to the local tastes of the city the show found itself in. Local jokes were inserted into stock skits and a burg’s major ethnic groups were played to. Nowhere was this big tent approach as complex and cacophonous as in New York City. With its divergent immigrant population, satisfying New York audiences compelled producers to cater to a discordant quilt of attitudes and backgrounds. Fortunately for the city’s showmen, every performer they needed for this unlikely task was locally available. New York was vaudeville’s heart, its mecca that all vaudevillians dreamed of.

The Olympian pinnacle of New York vaudeville was the Palace, at Broadway and 47th Street. Just thinking about the Palace brought a faraway gleam to a performer’s eye. In 1919 its brightest stars were commanding the heavenly salary of $2,500 a week. In the late 1920s, Eddie Cantor made $7,700 a week. However, by the early 1930s even the Palace was fading. Despite some glorious 1931 shows by Kate Smith, Sophie Tucker, and Burns and Allen, by the early 1930s it was largely a movie house.

The Paramount, where Ed produced his first show in November 1933, was also in transition. The theater was hedging its bet between film and vaudeville. For one ticket price, patrons saw both a live stage show and a Hollywood film, one following the other. This practice would become standard in New York theaters throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Sullivan’s Paramount revue, called

Gems of the Town

, shared the bill with the recently released musical comedy

Take a Chance

, starring James Dunn and June Knight. (Ed had reported on Knight’s love life in his column.)

Sullivan’s variety show at the Paramount was not classic vaudeville, though it was close. The program featured a similar up-tempo parade of fast-paced acts with an emcee as a central ringmaster. But Sullivan left out some of vaudeville’s most characteristic routines, like blackface minstrel singing and broadly ethnic acts. To headline the show he booked clown-comic Jimmy Savo, a top vaudeville star who had played the Palace in its prime; Charlie Chaplin had called him “the best pantomimist in the world.” That night at the Paramount he bounced and bounded all over the stage. The show’s reviewer, who enjoyed the show, wrote that Savo, “

knows when to strike; when to efface himself; when to leave the stage altogether; and how to get the maximum effect out of a sudden, unheralded return.” Sharing the bill with Savo were two tap dancing acts, Betty Jane Cooper and the Lathrop Brothers, and an acrobatic troupe, the Uierios. Based on his other shows from this period, it’s likely that Ed added a contemporary touch to his revue: introducing celebrity athletes or performers from the audience, whom he had invited to be on hand.

In essence, Sullivan’s Paramount stint was what was then called a variety show. It was updated vaudeville, a quick-stepping stage show offering something for everyone—comedy, music, acrobatics—without the most dated acts. (The terms “variety” and “vaudeville” had been used interchangeably to describe stage shows

for many years, and “vaudeville,” though the genre was declared dead, would still be used for years to come.)

Vaudeville’s near-death state probably contributed to Paramount Theatre manager Boris Morros’ decision to invite Ed to produce a show. As vaudeville withered, theater managers started using tricks like hiring columnists to produce revues. The advantage was twofold: a columnist could advertise his own show, and he could also cajole performers to appear for less by offering them publicity (or threatening to pan them). As

Time

magazine observed years later, “

Though at war with Winchell, Ed, like a good general, learned a great deal from his enemy. Winchell emceed a stage show at Manhattan’s Paramount, using the pressure of his column to line up good acts at a nominal cost. Ed did the same and earned $3,750 for a week’s stand.”