Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (56 page)

Read Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan Online

Authors: James Maguire

Nevertheless, that summer he let it be known—Paley’s simpatico notwithstanding—that his decisions about his show would not be guided by network management. Or, remarkably, even by his sponsors. Prompting a deep gasp of consternation from CBS and Ford, he announced that in July he would broadcast two programs from Las Vegas, otherwise known as Sin City.

Some of the show’s staff could hardly believe it. Ed … in Vegas? It was as if the parish priest had decided to open a strip joint. In 1958 the gambling mecca was completely unredeemed, the closest thing to pure perdition on domestic soil, an id of greed and sex poking through the staid American superego. That Ed, who forbade cleavage on his show and shot Elvis from the waist up—and always had something for the youngsters—would broadcast from Vegas was unthinkable. A reporter from

Variety

, echoing a question wondered by many, asked him if Vegas wasn’t a questionable location for

The Ed Sullivan Show.

“The fact that Jack Benny played a Vegas saloon made it okay for me and my sponsors,” Ed replied. That was patently untrue; the head of Ford’s ad agency, William Lewis, warned that the automaker did not want its name associated with Las Vegas. CBS’s Frank Stanton called the Vegas shows highly inadvisable.

But Ed didn’t care. After a successful ten-year run he was now in a position to lead rather than follow. And Las Vegas’ Desert Inn had offered to put him into a new income bracket in exchange for a Sullivan show. Wilbur Clark, one of the city’s most tireless hucksters, opened the $3.5 million Desert Inn in 1950 with the help of Moe Dalitz and other Cleveland organized crime figures; at some point in the late 1950s, Chicago mobster Sam Giancana also acquired an interest. (In 1967 Howard Hughes decided to buy the Desert Inn rather than move out.) Under Dalitz’s guidance, and fueled by low-interest loans from the Teamsters’ Pension Fund, the Desert Inn became a capstone of Vegas’ growth. Clark, as its public relations man, saw great value in Sullivan.

The Desert Inn hired the ritziest nightclub performers—Sinatra made his Vegas debut there in 1951, later joined by Jerry, Dino, and Sammy Davis. But the Rat Pack, although it attracted a fast crowd, couldn’t provide the patina of middle-class respectability that Sullivan could. Clark understood that bringing new dollars into Las Vegas meant burnishing its image, making it an acceptable destination for corporate junkets and—the idea was far-fetched in 1958–middle-brow tourists. Ed, with his position as unofficial Minister of Culture, was uniquely qualified to help with this.

The romancing of Ed by Las Vegas business interests had begun the previous fall, when the United Hotel Corporation of Las Vegas purchased his Connecticut estate. After his car crash, Ed lost interest in his country retreat. In truth, semirural South-bury was never a good match for Sullivan, who continued to enjoy rotating between Manhattan nightspots every evening. As he sold the estate, he explained that he was not made for country living. “

The noise was terrible,” he said. “I mean there’d be a cow mooing at four o’clock in the morning.” United Hotel took it off his hands for a handsome sum—$250,000—or more than double what he paid for it in 1954. The deal got sweeter. The Desert Inn agreed to cover all of his living expenses and pay him $25,000 a week for eight weeks, for a contract that stretched over two summers. After Ed broadcast two shows per summer from the hotel, he would stay for additional shows that wouldn’t be broadcast, while a guest host emceed his TV show.

As the grumbles of complaint from CBS and Ford grew into a chorus, Ed confided to Marlo Lewis: “

I don’t give a damn what any of them feel about this deal. I’ve busted my back … running from one city to another. I’m tired of traveling. I’m tired of putting on shows for the CBS affiliates. I’m tired of shaking hands with the Lincoln Mercury dealers, signing autographs, hearing people tell me how surprised they are

that I can smile—especially when my ulcer is knocking me out and I don’t want to smile. A few weeks in that Las Vegas sunshine will do me a world of good and it won’t hurt anyone else on the show either. And I’m not about to turn down this pot of gold that Wilbur’s throwing at me … and nobody’s gonna stop me from taking it!”

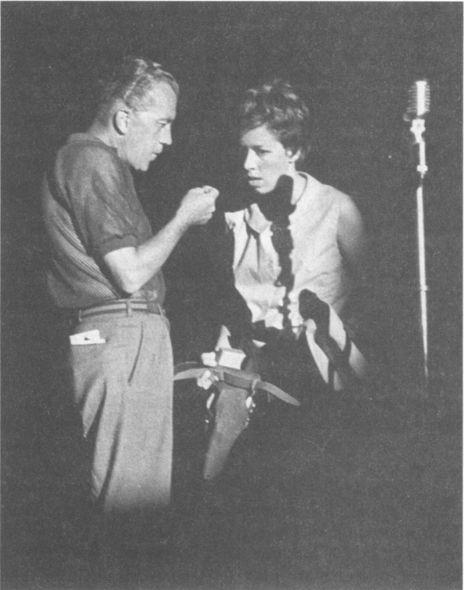

Giving instructions to Carol Burnett in rehearsal, Las Vegas, 1958. Sullivan scandalized CBS by producing a show from Sin City in the 1950s. (Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

The family show that Ed presented from the Desert Inn was in marked contrast to the hotel’s typical fare. Esther Williams, known as “America’s Mermaid” for the string of MGM hits that showcased her aquatic skills and bathing suit pulchritude, introduced “water babies,” children diving into swimming pools. Williams gave a little girl a piggyback ride in a pool, introduced the AAU synchronized swimming team, and blew a big kiss at the camera (Ed was furious at her for displaying too much cleavage). “Jumping Joe” Monahan performed a trampoline act, Carol Burnett did a stand-up routine about braces, and the Kirby Stone Four sang “Lazy River” (the appearance led to a Columbia Records contract for the vocal group). The show was a hit in Vegas. “

People flocked to see it—we had full houses,” recalled Burnett.

The following Sunday’s program was a reprise, with an Olympic diving champion, a ventriloquist and a magician for the kids, and the Four Preps singing “Lazy Summer Night.” Sullivan asked Wilbur Clark to take a bow from the audience. And, as if living in a parallel universe not connected to America in 1958, Ed touted the gambling mecca’s churches and schools as well as its entertainment and casino attractions.

Based on his Desert Inn broadcasts, viewers at home might have deduced that Las Vegas was a slightly risqué suburb of Oklahoma City.

As the 1958–59 season began, Ed’s traditional variety format seemed to have grown too small for him. Topping his broadcast produced in Brussels, he began the season by planning shows from Alaska, the Hawaiian Islands, and Asia. He turned his trips into travelogues that he presented along with other acts on Sunday evenings. In his Asian travelogue, the black-and-white footage was like his own home movie, as he played baseball with Japanese schoolchildren, talked about the architecture in Hong Kong—“The most exciting place on the globe,” he called it—and surveyed Istanbul with Sylvia. The beauty of the Turkish city “will make it one of the great tourist spots in the world,” he opined, as the camera panned over ancient minarets, though it’s doubtful he changed travel plans in many American living rooms with that claim.

Part of his wanderlust was a competitive desire to go where

Maverick

could not. The Western was regularly trouncing him in the Nielsens, even with the ratings jolt delivered by his increased rock ’n’ roll bookings. But his international shows gave him an advantage that

Maverick

couldn’t claim: they became news events, covered in newspapers across the country. In particular, his Brussels broadcast had generated an untold fortune in free publicity.

His interest in internationalizing the show, however, was about more than ratings. He began envisioning a time when the show would grow into something larger than entertainment. Ed was, after all, a reporter and columnist, and had worked on newspapers since his teens. He never stopped seeing himself as a newshound. One of his

personal secretaries recalled that even in the 1960s, if he placed a call he identified himself as “

Ed Sullivan, of the

News.

” (In fact he never gave up his

Daily News

column throughout his television career.) He had always included some element of current events or public service on the show, like the Eleanor Roosevelt tribute to Israel, or his chat with civil rights activist Ralph Bunche, or—a favorite cause of his—a spokesperson from the Association of Christians and Jews.

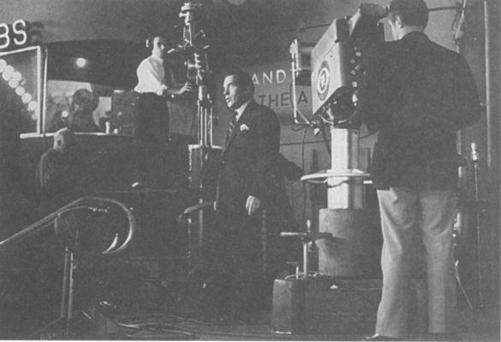

Live television, circa 1958: the Sullivan show was broadcast live throughout its twenty-three-year run. (Globe Photos)

In the fall of 1958 he began thinking of expanding the role of current events on the show, and of expanding his own role, too. He wanted to build upon his success as an impresario to become a producer who handled both news and entertainment; he imagined that these two forms could be mingled, which in television at that time was unheard of. He hoped to become, as

Journal-American

columnist Atra Baer wrote after talking with him, “

the Lowell Thomas of variety show business.” Thomas had been an adventurous roving radio journalist who produced stories from Europe in both world wars, as well as from the Middle East and China. Ed’s own international shows were a form of this, yet he hoped for much more.

He began lobbying the CBS news department. While he had no desire to be a network newsman, he wanted to have input, to be called upon to comment on issues of the day, much as he did in the

Daily News.

His entreaties to the network news division met with no response. At one point Ed invited legendary CBS newsman Edward R. Murrow on the show in an attempt to form a bridge between himself and the news department. Murrow was flattered by the attention—a bevy of showgirls requested his autograph—and he appreciated Ed’s interview. But the door was still shut. Murrow, in fact, in October 1958 gave a speech decrying prime-time television as full of “

decadence, escapism, and insulation from the realities of the world in which we live,” using

The Ed Sullivan Show

as an example.

As Ed sought to shift his role, it was as if he had outgrown the traditional variety format. At age fifty-seven, he had been producing stage shows for more than twenty-five years. He had clearly mastered the format; indeed he was

the

master of the format. He had accomplished everything he had set out to do. He had hungered to be a nationally famous broadcast star, and, without being able to sing, tell jokes, or be charming, had done so. But fame, apparently, hadn’t proven to be a high enough mountain. The inner force that had driven him to success was still there. Now that he had achieved what he had always wanted, he saw a bigger vista to conquer.

In December 1958 he announced that CBS had hired him to produce a program apart from his Sunday show, to be called

Sullivan’s Travels.

He would use his annual summer vacations—he certainly didn’t want to relax then—to produce four to six ninety-minute travelogue-documentaries. His first would be about India, and he planned pieces from West Germany, Vienna, Rio de Janeiro, and other locations. Yet even the

Sullivan’s Travels

series wasn’t enough—he was interested in serious journalism, insightful coverage and commentary that spotlighted global events.