Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (57 page)

Read Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan Online

Authors: James Maguire

The network didn’t see him in this role, despite having hired him to produce the travelogues. That CBS never invited him to give his opinion in year-end wrap-ups of national and international news was deeply frustrating for him. “

Why the hell not!” he exclaimed to Marlo Lewis. “I’ve had thirty years’ experience as an on-the-line reporter. When it involves the news, they won’t call me! But when they hold their drunken station-owner conventions and want to look impressive, they call on me to put on a show!”

However, the fact that CBS had not the slightest whit of interest in his dream didn’t deter him. He had always plunged headfirst toward his goals, regardless of what others thought. And now, as he hoped to enlarge the show’s concept and his own role, becoming the new Lowell Thomas, he pushed forward with the same headstrong motion.

Ed saw a chance to score the definitive news scoop as the rebel uprising in Cuba came to a head in the late fall of 1958. Led by Fidel Castro and Dr. Ernesto “Che” Guevera, the rebels appeared to be overtaking the Cuban army, edging ever closer to the capital city of Havana. By late December the situation dominated American news, as more than three thousand people died in house-to-house fighting. Rumors circulated that notoriously corrupt Cuban president Fulgencio Batista was preparing to flee.

As Castro took control of Cuba in early January, his political orientation was unclear to U.S. observers. Was he a communist, or merely a fervent nationalist? The son of a wealthy sugarcane farmer, educated in Jesuit schools and the University of Havana law school, he was gifted at public relations. In April 1959, four months after the revolution, the American Society of Newspaper Editors invited him to the United States. During his visit he declared himself in favor of a free press and against dictatorships; he told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that American property would not be nationalized. In November 1959—almost a year after he took power—the deputy director of the CIA informed a Senate committee, “

We believe Castro is not a member of the Communist Party and does not consider himself to be a communist.”

In the wake of the revolution, many Cubans viewed Castro as a folk hero. He entered Havana for the first time on January 8, and though the country was still in disorder—and still contained Batista loyalists—he walked the streets unarmed. His enormous popularity was evident as massive crowds lionized him in a spontaneous parade. A carnival atmosphere prevailed, with mobs looting hotels and casinos, and throngs celebrating Batista’s overthrow by waving flags and honking horns around the clock.

While it looked like pandemonium to most observers, to Ed it looked like an opportunity. Getting the first television interview with Castro would force CBS to recognize him as a newsman. And since the eyes of the world were on this small nation in turmoil, flying there would thrust him onto the world stage. But if he was going to bag the first Castro TV interview he had to move posthaste. Ed called Jules Dubois, the Latin American correspondent for the Chicago

Tribune

, which was the

Daily News’

parent company. Dubois, a fierce anticommunist who had a good rapport with Castro, agreed to set up an interview. (Some Cuban revolutionaries suspected that Dubois worked for the CIA, a suspicion that was never confirmed.) Sullivan and Dubois made arrangements to rendezvous at the Havana airport.

To gather a crew, Ed certainly wasn’t going to call the CBS news department; he was scooping them. Instead, a Sullivan assistant called a young CBS cameraman named Andrew Laszlo, who worked on the situation comedy

The Phil Silvers Show

, and asked him to assemble a crew. (Laszlo’s later career as a cinematographer included more than forty feature films, including

Star Trek V

in 1989.) Speed and secrecy were critical to Ed’s plan. On Sunday, Laszlo was told to prepare for a Wednesday

afternoon departure to the Dominican Republic; he was told he would film an interview with Dominican president Rafael Trujillo. Laszlo hired a soundman and another assistant and, planning for a shoot in Trujillo’s presidential palace, packed a heavy-duty movie camera used in making full-length features.

Sullivan and Andy Laszlo had worked together before, and Ed had come to like and trust the young cameraman, inventing an affectionate nickname for him, “Andy-roo.” That past summer Laszlo had filmed locations in Ireland and Portugal for Ed’s travelogue shows. In Ireland, they were seated together at a restaurant with about twenty crewmembers, many of whom were making petty demands as waiters took their orders. Ed, growing impatient with the crew’s self-centered fussing, took Laszlo by the arm. “Andy-roo,” he told him,

“you and I are getting out of here, we’re going to go get a real steak.” As Laszlo recalled, the two of them went to a spot Ed knew, a “fantastic little pub, him with his milk, and me with my steak.” (Ed’s ulcer continued to plague him, hence the milk.) They sat there until closing time, conversing throughout the evening. In Spain, Sullivan and Laszlo were having dinner with a few other people at a nightclub when Ed saw a Hungarian husband and wife dance team he enjoyed. He asked Laszlo, a native Hungarian, to invite the couple on his show. But the dancers had no knowledge of American television and turned him down.

Now, aboard a plane presumably bound for the Dominican Republic, Laszlo wasn’t sure what to think when Sullivan sat down next to him with a grave look. Ed sat sipping a glass of milk and, for several moments, said nothing. “

Andy-roo, I lied to you,” he finally said, explaining that the story about the Dominican Republic had been merely a cover. When Laszlo realized he was headed for Cuba—with the country still embroiled in violence—he told Sullivan he needed to call his wife as soon as he landed. Ed assured him that this was unnecessary because his office was informing the crew’s wives. Yet this wasn’t true. Ed was telling no one. He couldn’t air the interview until Sunday, and he didn’t want a news crew to hear about his plan and beat him to the story. Unbeknownst to Sullivan, Ted Ayers, the producer of CBS news program

Face the Nation

, had been working on arranging a Castro interview for weeks. Like Sullivan, Ayers was at that moment heading for Havana, with the understanding that the Cuban leader would grant him an interview in a studio there.

When Sullivan and his crew landed in Havana that evening it wasn’t clear that the revolution was over. Castro’s soldiers, clad in jungle green and carrying carbines, swarmed the airport. Known as Fidelistas, these revolutionaries were attempting to control the mob who frantically wanted to leave, with limited success. Terrified Cubans pushed and shouted to secure a spot on an outbound plane. Amid the roiling chaos Sullivan rendezvoused with Jules Dubois, who told him that Castro wasn’t in Havana. Somehow they needed to travel to Matanzas, a port city sixty miles to the east, a difficult trip in the dark.

The easiest way there was by small plane, and a pilot claiming to be Fidel’s official pilot agreed to take them in his Beechcraft six-seater. But as he spoke he kept weaving back and forth, apparently deeply inebriated from days of celebration. Ed, eyeing the man’s condition, diplomatically pointed out that his crew’s gear was too big for the plane. Dubois conferred with some nearby Fidelistas, who gathered a fleet of six taxicabs. The soldiers accompanied them, so each taxi had its own submachine gun-toting chaperone in the front seat to allow them passage through the

many roadblocks. Laszlo recalled the tension as they traveled with the Fidelistas through the Cuban countryside at night: “These people were scary just to look at, and to be next to them was even scarier.” Ed, however, played down the danger, and seemed unconcerned.

When they pulled into Matanzas sometime around midnight the city appeared deserted, until they came to the village square. Gathered there were thousands of townspeople listening with rapt attention to Castro, who was holding forth at the tail end of a three-hour speech. As the Cuban leader spoke, Laszlo started setting up his camera in a nearby building, only to encounter a major obstacle: the building didn’t have the correct electrical current to power his camera. Having packed for the Dominican Republic’s presidential palace, he wasn’t equipped for Cuba’s rudimentary power grid. He frantically searched the building. After anxious minutes he found an outlet with—he hoped—sufficient current, near where the interview would take place. By the time his gear was set up and Castro was ready it was after 1

A.M.

As the Cuban leader entered the interview room, dozens of his bearded soldiers rushed in with him, bringing a dense cloud of acrid cigar smoke. Dubois scrambled to convince some of them to leave to make space for the interview. Fidel was in an expansive mood and greeted Sullivan and his crew cordially. But suddenly, as they were exchanging greetings, a sharp explosive sound punctured the room—everyone gasped and ducked, and the Fidelistas turned their carbines to the ready. After a tense moment they realized that a soldier had tripped into a camera light, causing it to shatter.

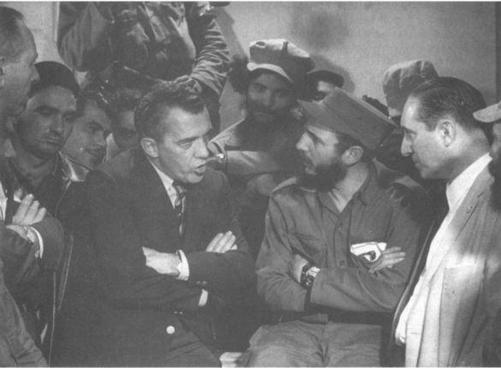

Following some short preliminaries the interview finally began, with Sullivan and Castro sitting on an old wooden desk. Ed, dressed in the same businesslike coat and tie he wore to host his show, seemed to almost lean into Castro, who was clad in combat fatigues with a sidearm. The two were surrounded by soldiers, one of whom kept a Tommy gun trained over Ed’s head through part of the interview. Sullivan’s demeanor was not that of the stiff and stilted Sunday night show host. Rather, he was closer to the feisty bantamweight that he often was offstage. The interview, at least initially, began as a mano a mano confrontation.

At one point, Ed asked Castro if he was a communist. The Cuban leader “

reacted violently,” Laszlo recalled. “He almost jumped off the desk. He ripped open his shirt and pulled out this very beautiful crucifix, and bellowed,

‘I’m a Roman Catholic, how could I be a communist?’

” At the sound of Castro’s pique the Fidelistas shifted their carbines uneasily. Perhaps in response, Ed followed with a softball: “Some refer to you as the liberator, the George Washington, of Cuba. Are you the George Washington of Cuba?” Castro, now smiling and clearly relishing the question, gave a long and windy answer that released the tension in the room. But Ed wasn’t through with the tough questions. Jabbing a finger toward Castro for emphasis, he asked, “In Latin America, over and over again, dictators have come along, they’ve raped the country, they’ve stolen the money, millions and millions of dollars, tortured and killed people. How do

you

propose to end that in Cuba?”

“

[It will] be easy,” Castro replied, in broken English. “By not permitting any dictatorships to come to rule our country. You can be sure that Batista is, or will be, the last dictator of Cuba.” Moreover, he claimed, the country would improve its democratic institutions. At several points Laszlo needed to stop the interview to reload his camera, which required Sullivan or Castro to repeat their previous statement.

Laszlo found Castro remarkably adept at resuming his reply mid thought, or repeating his answers verbatim to whatever question Ed asked.

With Fidel Castro, January 1959. Sullivan flew to Cuba just days after the revolution hoping to land the first TV interview with the new Cuban leader. (CBS Photo Archive)

By the end of the nearly hour-long interview the two men warmed to each other. With a disarming smile, Castro said he had never dreamed he would have a chance to address so many English-speaking people, prompting a good-natured chuckle from Ed. Sullivan promised Castro a donation of $10,000 in a gesture of support for the revolution’s widows and orphans. A courier delivered a note to Castro from Che Guevera, after which the Cuban leader signaled that the interview had to end. (Castro was headed off to do his interview with

Face the Nation;

in fact, he had kept the CBS-TV news crew waiting while completing his Sullivan interview, though Ed didn’t know this.) Before the camera stopped filming, Ed introduced Jules Dubois and thanked him for arranging the interview. The Dubois introduction had an added benefit. Mentioning the reporter’s Chicago

Tribune

pedigree—a paper never accused of codling communists—helped establish that Ed hadn’t just interviewed an enemy of the United States.