Imponderables: Fun and Games (4 page)

Read Imponderables: Fun and Games Online

Authors: David Feldman

T

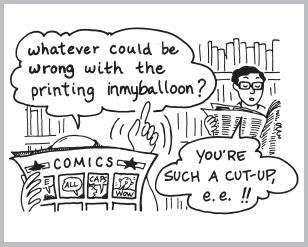

he cartoonists we contacted, including our illustrious (pun intended) Kassie Schwan, concurred that it is easier to write in all caps. We’ve been printing since the first grade ourselves and haven’t found using small letters too much of a challenge, but cartoonists have to worry about stuff that never worries us. Using all caps, cartoonists can allocate their space requirements more easily. Small letters not only vary in height but a few have a nasty habit of swooping below or above most of the other letters (l’s make a’s look like midgets; and p’s and q’s dive below most letters).

More important, all caps are easier to read. Mark Johnson, archivist for King Features, reminded us that comic strips are reduced in some newspapers and small print tends to “blob up.”

We wish that our books were set in all caps. It would automatically rid us of those pesky capitalization problems. While we’re musing…we wonder how

Classics Illustrated would handle the type if it

decided to publish a comics’ treatment of e. e. cummings’ poetry?

Submitted by Carl Middleman of St. Louis, Missouri.

W

e’re sure you’ll be overjoyed to learn that everyone we talked to agreed on the paramount issue: that crossbar at the top of the frame makes men’s bikes far sturdier than women’s. After centuries of experimentation, manufacturers have found that the best strength-to-weight ratio is maintained by building frames in the shape of diamonds or triangles. Without the crossbar, or as it is now called, the “top tube,” part of the ideal diamond structure is missing.

A man’s bicycle has its top tube parallel to the ground; on a ladies’ bicycle, the top tube intersects the seat tube several inches above the crank axle. Why is the women’s top tube lower than the male’s?

The tradition is there for no other reason than to protect the dignity and reputations of women riding a bicycle while wearing a skirt or dress. Now that most women bicyclists wear pants or fancy bicycle tights, the original purpose for the crossbar is moot, although Joe Skrivan, a product-development engineer for Huffy, points out an additional bonus of the lower top tube: it allows for easy mounting and dismounting.

Skrivan notes that the design difference creates few complaints from women. Casual women bicyclists don’t necessarily need the rigidity of the higher crossbar. Serious female bicyclists buy frames with exactly the same design as men’s.

Submitted by Linda Jackson, of Buffalo, New York.

T

ennis as we know it today is barely over a hundred years old. A Welshman, Major Walter Clopton Wingfield, devised the game as a diversion for his guests to play on his lawn before the real purpose for the get-together—a pheasant shoot. Very quickly, however, the members of the Wimbledon Cricket Club adopted Wingfield’s game for use on their own underutilized lawns, empty since croquet had waned in popularity in the late eighteenth century.

Long before Wingfield, however, there were other forms of tennis. The word “tennis” first appeared in a poem by John Gower in 1399, and Chaucer’s characters spoke of playing “rackets” in 1380. Court tennis (also known as “real” tennis) dates back to the Middle Ages. That great athlete, Henry VIII, was a devotee of the game. Court tennis was an indoor game featuring an asymmetrical rectangular cement court with a sloping roof, a hard ball, a lopsided racket, and windows on the walls that came into play. Very much a gentleman’s sport, the game is still played by a few diehards, though only a handful of courts currently exist in the United States.

Lawn tennis’s strange scoring system was clearly borrowed from court tennis. Although court tennis used a fifteen-point system, the scoring system was a little different from modern scoring. Each point in a game was worth fifteen points (while modern tennis progresses 15–30–40–game, court tennis progressed 15–30–45–game). Instead of the current three or five sets of six games each, court tennis matches were six sets of four games each.

The most accepted theory for explaining the strange scoring system is that it reflected Europeans’ preoccupation with astronomy, and particularly with the sextant (one-sixth of a circle). One-sixth of a circle is, of course, 60 degrees (the number of points in a game). Because the victor would have to win six sets of four games each, or 24 points, and each point was worth 15 points, the game concluded when the winner had “completed” a circle of 360 degrees (24 X 15).

Writings by Italian Antonio Scaino indicate that the sextant scoring system was firmly in place as early as 1555. When the score of a game is tied after six points in modern tennis, we call it “deuce”—the Italians already had an equivalent in the sixteenth century,

a due (in other words, two points were

needed to win).

Somewhere along the line, however, the geometric progression of individual game points was dropped. Instead of the third point scoring 45, it became worth 40. According to the

Official Encyclopedia of Tennis

, it was most likely dropped to the lower number for the ease of announcing scores out loud, because “forty” could not be confused with any other number. In the early 1700s, the court tennis set was extended to six games, obscuring the astronomical origins of the scoring system.

When lawn tennis began to surpass court tennis in popularity, there was a mad scramble to codify rules and scoring procedures. The first tennis body in this country, the U.S. National Lawn Tennis Association, first met in 1881 to establish national standards. Prior to the formation of the USNLTA, each tennis club selected its own scoring system. Many local tennis clubs simply credited a player with one point for each rally won. Silly concept. Luckily, the USNLTA stepped into the breach and immediately adopted the English scoring system, thus ensuring generations of confused and intimidated tennis spectators.

There have been many attempts to simplify the scoring system in order to entice new fans. The World Pro Championship League tried the table-tennis scoring system of twenty-one–point matches, but neither the scoring system nor the League survived.

Perhaps the most profound scoring change in this century has been the tiebreaker. The U.S. Tennis Association’s Middle States section, in 1968, experimented with sudden-death playoffs, which for the first time in modern tennis history allowed a player who won all of his regulation service games to lose a set. The professionals adopted the tiebreaker in 1970, and it is used in almost every tournament today.

Submitted by Charles F. Myers, of Los Altos, California.

W

ell, who said life was fair? It turns out that this blatant discrimination occurs not because anyone wants to persecute punters particularly but for the convenience and accuracy of the scorekeepers. Jim Heffernan, director of Public Relations for the National Football League, explains:

Punts are measured from the line of scrimmage, which is a defined point, and it sometimes is difficult to determine exactly where the punter contacts the ball. Field goals are measured from the point of the kick because that is the defined spot of contact.

Submitted by Dale A. Dimas of Cupertino, California.

W

e have a nifty secret for curing the morning blahs—sleep through them. Yes, we admit it: We’re night people. We sleep until noon, run the shower, and flip the radio on to WHTZ, better known as Z100 in the New York City metropolitan area, and listen to the midday jock, Human Numan. Z100 is what the radio trade calls a CHR (Contemporary Hits Radio) station, a modern mutation of the old Top 40 format. It has a small playlist of current songs.

Human’s a terrific disc jockey. He’s not full of himself. Doesn’t reach for laughs. But we have one big complaint: He rarely, if ever, identifies songs. As we’re writing this chapter, we’ve heard the new New Order single played at least twenty-five times on his show but have yet to hear the title identified.

Fate threw us into Human’s lap one day, and we got to talk to him about this Imponderable. DJs have two options in identifying a song: introducing it before they play it, or “frontselling”; or playing the song and announcing the name of the recording artist and/or song afterward, or “backselling.” The first thing that Human wanted to let

Imponderables readers know is

that the vast majority of DJs, especially in major urban markets, have little artistic control over what they play and what they say on the air. In a letter, Human discussed the pressures and constraints of a DJ in his kind of format and used a fifteen-minute segment of his show to demonstrate:

Think of the DJs in the Top 100 markets as actors or football players. The coach designs the plays and the playwright gives the actor his lines: It’s the same for the American DJ.

The program director (PD) is the second most powerful person at a radio station, behind the general manager (GM). The PD hires the DJs and has the power to fire them, promote them, and has complete control over their shows.

The PD creates a structure for the DJ’s show called a

format clock

. This is a paper clock that has no hour hand because it is used every hour. On this clock, for example, it says where the one is: SEGUE, to proceed without pause (radio language for “shut up, just play the next song”). A DJ can never talk where the PD has indicated SEGUE on his routine clock.

Then between the 1 and 2 on the clock, somewhere about seven minutes past the top of the hour, the PD might indicate LINER. This element means that the DJ has been given a 3" by 5" card with the “lines” he should ad lib or read verbatim, depending upon how strict the PD is. The LINER is a very important sell, one that the station must convey without any DJ clutter. The liner should not be diffused with additional information, such as a backsell of the previous record.

The next element marked on the clock, at perhaps twelve minutes past, might say “BACKSELL/FRONTSELL NEW MUSIC—OPEN SET.” This element indicates that every hour at this point, the third or fourth record in the hour will be a brand new song that the PD wants to identify to the listener. Aha! The DJ may now ID the song. But notice he or she may ID only when indicated by the clock. Here my format clock also said “OPEN SET.” This is the time when a DJ is free to express himself or herself (as long as the DJ remembered to sell the NEW MUSIC in this case!).

I’m just the tailback running up the left side, running a play the coach has called. I try to put my own spin on it, and dodge the tackles, but it is somebody on the sidelines calling the play.

PDs love to use a private Batphone setup in virtually every studio in every radio station. It’s called the HOTLINE. If you don’t follow the format, guess who’s calling?

So if it’s the PD calling the shots, why don’t PDs instruct DJs to identify more songs? We talked to scores of disc jockeys and PDs and found absolutely no consensus about the wisdom of frequent song identification. Here are some of the most important reasons for lack of IDs, followed by the rebuttal case for more IDs.

1.

Research shows that listeners want more music and less talk.

Jay Gilbert, afternoon drive DJ on WEBN, Cincinnati, one of the first Album-Oriented Rock stations, told us that every research survey he has ever seen has indicated that most listeners want DJs to shut up and play more music. Originally, the relative lack of commercials and DJ chatter on FM helped the fledgling band win over AM listeners.

Sure, says Cleveland radio personality Danny Wright, who is generally against overdoing IDs, every poll he has seen in his twenty years in broadcasting indicates that listeners hate jocks who talk too much. But then who are the most popular people on the air? According to Wright, “the folks with the oral trots”—Rush Limbaugh, Howard Stern, Rick Dees, Scott Shannon, etc. Wright believes that if a jock has nothing to say, he is better off just playing music, but that audiences love patter if it is entertaining.

2.

IDs slow down the show.

In order to speed up the pace of the show and to provide the illusion of more music being played, stations will do everything from playing records at a higher than normal speed to instructing DJs to talk over the music. To many PDs, back announcing, in particular, is just dead air, particularly when the time could be devoted to more jingles promoting the call letters of the station.

Of course, the five or ten seconds devoted to identifying a song could be spent playing more music, but then perhaps a radio show should be more than a jukebox with commercials. Al Brock, a PD and on-air personality at WKLX, an oldies station in Rochester, New York, told

Imponderables

that identifying a song is a way of connecting the DJs with the music, showing listeners that the jocks are interested in and committed to the music. PDs who are for frequent IDs see them as part of the music programming, while anti-ID PDs see them as part of the talk. Brock feels strongly enough about the issue to try to frontsell or backsell every song on the station (which can’t always be done, because of time constraints).

3.

Why tell audiences what they already know?

A classical music station usually IDs every selection it plays, because the audience might not be able to recognize a particular piece or the conductor and orchestra. But does a DJ really have to tell an audience “That was Whitney Houston and ‘I Will Always Love You’?”

The answer of the pro-ID side is, “Yes, you do.” Al Brock informed us that most people know some songs by titles and other by artists but that few can remember both. For example, after the Righteous Brothers’ “Unchained Melody” was rereleased during the popular run of the movie

Ghost

, the song was not only played on oldies stations (it never stopped being played there) but promoted as if it were a new song on many CHR and AC (Adult Contemporary) stations. Yet listeners constantly called to ask the name of the song or the group who sang it. Another DJ told us that every time he plays Paul Stookey’s “The Wedding Song” (the title is not part of the lyrics), even if he front- or backsells it, he gets calls asking, “What song was that?”

Obviously, the need for IDs depends upon the format of the station and the familiarity of a given song. Virtually every PD and DJ we spoke to identified a brand new song, one that the station has been playing for two to four weeks. (These songs are called “currents.”) All agreed that the songs least needed to be ID’d are songs that are no longer current but are still popular and haven’t left the playlist. These are known as “recurrents” and are usually played less than “currents” but more than oldies. Some PDs argue that oldies don’t require IDs because they are so familiar, but even this strategy has pitfalls, for oldies stations are trying to attract younger listeners, including people who might not have been alive when a song was recorded.

4.

IDs create clutter.

An old broadcasting bromide is that each music set on a radio show should stress one thought. Considering that there are many elements in a radio show—music, talk, promos, ads, weather, contests, jingles—IDs can cause more confusion than enlightenment. Steve Warren, a veteran New York radio personality now heading his own programming consulting company, MOR Media, reminded us that for most of the audience, radio is a secondary medium. Most listeners are doing other things, such as driving cars, sewing, or taking a shower, while listening to the radio. Overloading any format with too much information can backfire.

Even pro-ID programmers realize that, for example, during morning drive shows, when information about weather and traffic may be paramount and commercials are most frequent, backselling may not be prudent. They often fine-tune their volume of ID’s by daypart.

5.

IDs slow the momentum of the show.

One of the tenets of CHR radio is “always move forward.” The name of the ratings game in radio is to keep listeners as long as possible. Unlike television, where viewers generally have some loyalty to particular shows and are likely to stick with them for the half-hour or hour, PDs are acutely aware that listeners in automobiles have push-buttons that can “eject” their station the moment they hear an unwanted song or one too many commercials. This is one reason why many stations start a new song before the DJ talks over it—subliminally, this tells the listener, “Don’t worry, there is no advertisement coming up.”

One of the main strategies for keeping us tuned in longer is to promote what is coming up next. As Danny Wright puts it,

Never talk about last night or a movie you saw last week or what you just played. Billboard the next few tunes and events to keep listeners sticking around.

PDs employing this strategy often frontsell. Before a commercial break, a jock might say, “Coming up, the new Eric Clapton, Whitney Houston, and an oldie by the Beatles.” The hope is that the listener will stay glued to the station if she likes one or more of the songs.

Of course this strategy can backfire too. If a listener would rather hear fingernails on a blackboard than Whitney Houston, he may desert the station, even if he was mildly curious about the identity of the Beatles oldie.

Many of the “more music, less talk” stations feature “music sweeps,” in which five or more songs are played in a row without commercial interruption. Frontselling eight songs at a time is tedious, and backselling is deadly. Some stations solve the problem by frontselling only one or two songs and doing the same on the back end. Some feature what Al Brock calls “segue assists,” in which the jock IDs the song before or after every record.

6.

Selling records isn’t a radio station’s job.

We spoke to several radio programmers who echoed this sentiment. The trade association of the recording industry, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), launched a campaign to promote IDs, plastering stickers on DJ record copies saying, “When You Play It, Say It,” the “It” meaning title and artist. In 1988, the RIAA released a study of over one thousand radio listeners, between the ages of twelve and forty-nine, indicating that about two thirds of the respondents would like more information about the records they heard on radio. Listeners between twenty-five and forty-nine years old were particularly vehement, and several programmers we spoke to revealed that the lack of IDs has surpassed “too much talk, not enough music” as the number one complaint of listeners.

Increasingly, radio stations are conducting “outcall” research, telephoning listeners and asking them about their musical preferences. This type of research is of little value if respondents don’t know the titles and artists of the songs played on the stations. One PD we consulted, who wished to remain anonymous, indicated that his policy of heavy backselling had nothing to do with helping record companies:

We try to backsell as much as possible for two reasons. First, it answers the listeners’ primary question: What was that we just heard? Second, it helps us with our research. How are we supposed to ask listeners to call in our request line if they don’t know what they’ve heard on our station?

Consultant Steve Warren suggests that there

are

alternate ways of supplying listeners with information about titles and artists, including manned request lines and listener hotlines (in which an employee answers questions about the music, the station, contests, etc.). Warren indicated that at times it doesn’t hurt to have calls come in directly to the DJ—it’s a good way for jocks to stay in touch with their fans.

Disc jockeys have so many chores to perform besides listening to music that many are understandably not excited about IDs; after all, their time on the air is extremely limited. So, we guess we can’t be too hard on our very Human Numan for not frontselling or backselling every song. After all, he estimates that on his average three-hour shift, he speaks on-air for a grand total of

seven minutes

.

Submitted by the guy in the shower, New York, New York.

Postscript:

Since this chapter was written, Human Numan has left terrestrial radio for the less rigid format of Sirius Satellite Radio.