Imponderables: Fun and Games (10 page)

Read Imponderables: Fun and Games Online

Authors: David Feldman

R

arely has any Imponderable elicited such hemming and hawing. But then we found the brave man who would utter what others were merely hinting at. So we yield the floor to Scott J. Stevens, senior patent counsel for Thomson Consumer Electronics, a division of General Electric: “…the diagonal measurement is larger than either the horizontal or vertical measurement, hence making the picture appear as large as possible to potential customers.”

Submitted by John D. Claypoole, Jr. of Norwalk, Connecticut.

Thanks also to Mike Ricksgers of Saxonburg, Pennsylvania.

J

apanese society is sometimes accused of insularity, yet the country has not only adopted American baseball as its favorite team sport, but displays the names of its heroes in English. How did this happen?

Most historians date the birth of baseball in Japan to the early 1870s, at what is now Tokyo University. Horace Wilson, an American professor, taught students how to play. According to Ritomo Tsunashima, an editor and writer who writes a column about uniforms for

Shukan Baseball magazine in Japan, these

students were probably then wearing kimonos and hakama (trousers designed to be worn with kimonos).

In 1878, the Shinbashi Athletic Club established the first baseball team in Japan, and they were the first team to wear a uniform. The team’s founder, Hiroshi Hiraoka, was raised in Boston, Massachusetts, and bought the equipment and uniforms to conform to what he saw in the United States at that time. Tsunashima observes that in the early days of the game in Japan,

The players of baseball were fans of the Western style of life, and they were fond of Western culture. When exactly alphabet letters appeared on uniforms is unknown, but likely it was shortly after letters appeared on uniforms in the United States.

The first professional team in Japan that had uniforms with printed English words and names was founded in 1921, but disbanded in 1929. But in 1934, a U.S. all-star team containing such legendary figures as Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig visited Japan. To challenge the visitors, Japan assembled a team that eventually became the Yomiuri Giants. When the Giants returned the favor the following year and visited the United States, their uniforms contained the kanji (i.e., Japanese) alphabet and numbers, but this was an anomaly.

When the first professional baseball league formed in Japan in 1936, the players appeared with an English alphabet and Arabic numbers on their front—the Tokyo Giants appeared with “Giants” emblazoned on their chests. During World War II, kanji characters reappeared, as Western symbols were obviously frowned upon. Tsunashima writes:

Professional baseball continued during the bombing raids by the United States in 1943, but playing baseball was finally forbidden in 1944. After World War II, professional baseball started again with the English language [on the uniforms], and kanji letters were never used again.

Why has English superseded kanji, especially when amateur and school baseball teams usually use Japanese characters? We haven’t been able to find any answer more fitting than Robert Fitts’s, owner of RobsJapaneseCards.com:

Because it’s cool. Just the same as when people call me and say, “I want Japanese baseball cards written in Japanese,” and I have to tell them, “They don’t make them.”

Submitted by Marshall Berke and Chris Tancredi

of Brooklyn, New York.

J

im Heffernan, director of public relations for the National Football League, told

Imponderables that

NFL rules require that each home team provide twenty-four footballs for the playing of each game. The home team and the visiting team each provide additional balls for their pregame practice.

A “game ball,” contrary to popular belief, is not one football given to the winning side. Game balls are rewards for players and coaches who, as Heffernan puts it, “have done something special in a particular game.” The game-ball awards are usually doled out by the coach; on some teams, the captains determine the recipients.

The same holds true in college football. James A. Marchiony, director of media services for the National Collegiate Athletic Association, says, “Game balls are distributed at the sole discretion of each team’s head coach; a winning, losing or tying coach may give out as many as he or she wishes.”

Submitted by Larry Prussin, of Yosemite, California.

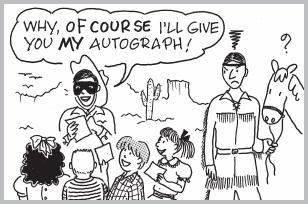

T

he classic western features a lone hero entering a new town and facing a villain who threatens the peacefulness of a dusty burg. The Lone Ranger, on the other hand, came with a rather important backup, Tonto. Leaving aside questions of political correctness or racism, calling the masked man the

Lone

Ranger is a little like calling Simon and Garfunkel a Paul Simon solo act.

Before we get to the “Lone” part of the equation, our hero actually was a ranger, in fact, a Texas Ranger.

The Lone Ranger started as a radio show,

first broadcast out of Detroit in 1933, created by George Trendle, and written by Fran Striker. The first episode established that circa 1850, the Lone Ranger was one of six Texas Rangers who were trying to tame the vicious Cavendish Gang. Unfortunately, the bad guys ambushed the Rangers, and all of the Lone Ranger’s comrades were killed. The Lone Ranger himself was left for dead. Among the vanquished was the Lone Ranger’s older brother, Dan.

So for a few moments, long enough to give him his name, the Lone Ranger really was by himself. He was the lone surviving Ranger, even if he happened to be unconscious at the time. Tonto stumbled upon the fallen hero and, while nursing him back to health, noticed that the Ranger was wearing a necklace that Tonto had given him as a child. Many moons before, the Lone Ranger (who in subsequent retellings of the story we learn was named John Reid) saved Tonto’s life! Tonto had bestowed the necklace on his blood brother as a gift.

When Reid regained his bearings, the two vowed to wreak revenge upon the Cavendish Gang and to continue “making the West a decent place to live.” Reid and Tonto dug six graves at the ambush site to make everyone believe that Reid had perished with the others, and to hide his identity, the Lone Ranger donned a black mask, made from the vest his brother was wearing at the massacre. Tonto was the only human privy to the Lone Ranger’s secret.

Not that the Lone Ranger didn’t solicit help from others. It isn’t easy being a Ranger, let alone a lone one, without a horse. As was his wont, Reid stumbled onto good luck. He and Tonto saved a brave stallion from being gored by a buffalo, and nursed him back to health (the first episode of

The Lone Ranger

featured almost as much medical aid as fighting). Although they released the horse when it regained its health, the stallion followed them and, of course, that horse was Silver, soon to be another faithful companion to L.R.

And would a lonely lone Ranger really have his own, personal munitions supplier? John Reid did. The Lone Ranger and Tonto met a man who the Cavendish Gang tried to frame for the Texas Ranger murders. Sure of his innocence, the Lone Ranger put him in the silver mine that he and his slain brother owned, and turned it into a “silver bullet” factory.

Eventually, during the run of the radio show, which lasted from 1933 to 1954, the duo vanquished the Cavendish Gang, but the Lone Ranger and Tonto knew when they found a good gig. They decided to keep the Lone Ranger’s true identity secret, to keep those silver bullets flowing, and best of all, to bounce into television in 1949 for a nine-year run on ABC and decades more in syndication.

The Lone Ranger was also featured in movie serials, feature movies, and comic books, and the hero’s origins mutated slightly or weren’t mentioned at all. But the radio show actually reran the premiere episode periodically, so listeners in the 1930s probably weren’t as baffled about why a law enforcer with a faithful companion, a fulltime munitions supplier, and a horse was called “Lone.”

Submitted by James Telfer IV of New York, New York.

W

e have received this Imponderable often but never tried to answer it because we thought of it as a trivia question rather than an Imponderable. But as we tried to research the mystery of Barney’s profession, we found that even self-professed “Flintstones” fanatics couldn’t agree on the answer.

And we are not the only ones besieged. By accident, we called Hanna-Barbera before the animation house’s opening hours. Before we could ask the question, the security guard said, “I know why you’re calling. You want to know what Barney Rubble did for a living. He worked at the quarry. But why don’t you call back after opening hours?” The security guard remarked that he gets many calls from inebriated “Flintstones” fans in the middle of the night, pleading for Barney’s vocation before they nod off for the evening.

We did call back, and spoke to Carol Keis, of Hanna-Barbera public relations, who told us that this Imponderable is indeed the company’s most frequently asked question of all Flintstone trivia. She confirmed that the most commonly accepted answer is that Barney worked at Fred’s employer, Bedrock Quarry & Gravel:

However, out of 166 half-hours from 1960–1966, there were episodic changes from time to time. Barney has also been seen as a repossessor, he’s done top secret work, and he’s been a geological engineer.

As for the manner in which Barney’s occupation was revealed, it was never concretely established (no pun intended) [sure]. It revealed itself according to the occupation set up for each episode.

Most startling of all, Barney actually played Fred’s boss at the quarry in one episode. Sure, the lack of continuity is distressing. But then we suspend our disbelief enough to swallow that Wile E. Coyote can recover right after the Road Runner drops a safe on Coyote’s head from atop a mountain peak, too.

Hanna-Barbera does not have official archives, so Keis couldn’t assure us that she hadn’t neglected one of Barney Rubble’s jobs. Can anyone remember any more?

Submitted by Rob Burnett of New York, New York.

I

n Scotland, the home of golf, courses were originally designed with varying numbers of holes, depending on the parcel of land available. Some golf courses, according to U.S. Golf Association Librarian Janet Seagle, had as few as five holes.

The most prestigious golf club, the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews, originally had twenty-two holes. On October 4, 1764, its original course, which had contained eleven holes out and eleven holes in, was reduced to eighteen holes total in order to lengthen them and make St. Andrews more challenging. As a desire to codify the game grew, eighteen holes was adopted as the standard after the St. Andrews model.