Imponderables: Fun and Games (13 page)

Read Imponderables: Fun and Games Online

Authors: David Feldman

F

ewer things are more annoying to us than receiving a magazine we put our soft-earned bucks down to subscribe to, and being rewarded for our loyalty by being showered with cards entreating us to subscribe to the very magazine we’ve just shelled out for.

Why is it necessary to have to clean a magazine of foreign matter before you read the darn thing? Because the cards work. Publishers know that readers hate them; but the response rate to a card, particularly one that allows a free-postage response, attracts more subscribers than a discreet ad in the body of the magazine.

Those pesky little inserts that fall out are called “blow-in cards” in the magazine biz. We thought “blow-out” cards might be a more descriptive moniker until we learned the derivation of the term from Bob Nichter, of the Fulfillment Management Association.

Originally, blow-in cards were literally blown into the magazine by a fan on the printer assembly line. Now, blow-ins are placed mechanically by an insertion machine after the magazine is bound. Nothing special is needed to keep the cards inside the magazine; they are placed close enough to the binding so that they won’t fall out unless the pages are riffled.

Why do many periodicals place two or more blow-in cards in one magazine? It’s not an accident. Most magazines find that two blow-in cards attract a greater subscription rate than one. Any more, and reader ire starts to overshadow the slight financial gains.

Submitted by Curtis Kelly of Chicago, Illinois.

L

isten carefully to any boxing match, or to any boxer shadowboxing, and you will hear a sniffing sound every time a punch is thrown. This sound is known to many in the boxing trade as the “snort.”

A “snort” is nothing more than an exhalation of breath. Proper breathing technique is an integral part of most sports, and many boxers are taught to exhale (usually, through their nose) every time they throw a punch. Scoop Gallello, president of the International Veteran Boxers Association, told

Imponderables that

when a boxer snorts while delivering a punch, “he feels he is delivering it with more power.” Gallello adds: “Whether this actually gives the deliverer of the punch added strength may be questionable.” Robert W. Lee, president and commissioner of the International Boxing Federation, remarked that the snort gives a boxer “the ability to utilize all of his force and yet not expend every bit of energy when throwing the punch. I am not sure whether or not it works, but those who know much more about it than I do continue to use the method and I would tend to think it has some merit.”

The more we researched this question, the more we were struck by the uncertainty of the experts about the efficacy of the snorting technique. Donald F. Hull, Jr., executive director of the International Amateur Boxing Association, the governing federation for worldwide amateur and Olympic boxing, noted that “While exhaling is important in the execution of powerful and aerobic movements, it is not as crucial in the execution of a boxing punch, but the principle is the same.” Anyone who has ever watched a Jane Fonda aerobics videotape is aware of the stress on breathing properly during aerobic training. Disciplines as disparate as weightlifting and yoga stress consciousness of inhalation and exhalation. But why couldn’t any of the boxing experts explain why, or if, snorting really helps a boxer?

Several of the authorities we spoke to recommended we contact Ira Becker, the doyen of New York’s fabled Gleason’s Gymnasium, who proved to have very strong opinions on the subject of snorting: “When the fighter snorts, he is merely exhaling. It is a foolish action since he throws off a minimum of carbon dioxide and some vital oxygen. It is far wiser to inhale and let the lungs do [their] own bidding by getting rid of the CO

2

and retaining oxygen.”

The training of boxing, more than most sports, tends to be ruled by tradition rather than by scientific research. While most aspiring boxers continue to be taught to snort, there is obviously little agreement about whether snorting actually conserves or expends energy.

Postscript:

Few answers have raised the ire of

Imponderables

readers as much as this discussion in

Why Do Clocks Run Clockwise

? Exponents of the martial arts, in particular, were not happy. Reader Rodney Sims e-mailed us:

In martial arts, you are taught not only to exhale when delivering a blow, but to vocalize along with this exhalation when you wish to deliver a particularly powerful blow. In Tae styles, this explosive exhalation is ke-ai (pronounced “keeeye”). It serves to focus the chi, which is one’s inner power or spirit located at one’s center (just below your belly button) and push it through the extremity delivering the blow.

The martial arts teach you that to control yourself, mind, body, and spirit, is to reach for perfection, and value is placed upon such control: involuntary functions can be controlled, more force can be delivered, and things outside of normal understanding can be understood. Martial arts philosophy aside, it seems logical to assume that so many people are taught to do it, and consequently practice this exhale, that it does work to focus one’s mind. From my experience, boards are easier to break when you

ke-ai

.

The problem is that even martial arts exponents don’t agree about the relationship between breathing and fighting. Reader Ryan Pentoney, a goshin ru specialist, thinks that the body receives sufficient oxygen through normal breathing patterns, and that exhaling just to gain power is probably counterproductive:

The time spent sharply exhaling converted into an inhale period would not be constructive, seeing as how these exhale periods occur at the time the fighter is throwing a punch (in the case of boxing)—it would not be advisable…try throwing a punch or two in succession while inhaling, and then while exhaling. You will probably find that it is harder to inhale while punching (holding your breath isn’t very good either, as you inhibit gas flow altogether).

I believe that there is a greater purpose to the exhaling than simple gas exchange or a psychological reason. I have been taught that exhaling upon striking, blocking, exploding into a stance, or dodging out of the way of an attack severely minimizes the risk of having the wind knocked out of you. When you exhale quickly, your abdominal muscles tighten up and also protect your diaphragm. The opposite is true when you inhale. The end result is disastrous when you are struck in the upper abdominal area when you inhale, and in a fight can spell the end.

Several readers added that in activities ranging from abdominal crunches to weightlifting, the practitioner is advised to exhale at the point where the most strength is needed. The real Imponderable remains: Why don’t the boxing trainers themselves offer the same reasoning?

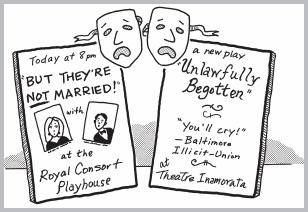

C

all us grumpy, but we think laying out a hundred bucks to listen to a caterwauling tenor screech while chandeliers tumble, or watching a radical reinterpretation of

Romeo and Juliet as a metaphor for

the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is plenty illegitimate. But we are etymologically incorrect; the use of the word

legit dates back to the end of the nineteenth

century, when it was used as a noun to describe stage actors who performed in dramatic plays. It soon became a term to describe just about any serious dramatic enterprise involving live actors.

And to this day, “legitimate” is used to describe actors who toil in vehicles that are considered superior in status to whatever alternatives are seen as less prestigious. As Bill Benedict of the Theatre Historical Society of America points out, one of the definitions of

legit in The Language of American Popular Entertainment is:

Short for

legitimate

. Used to distinguish the professional New York commercial stage from traveling and nonprofessional shows. The inference is that

legit

means stage plays are serious art versus popular fare.

Back in the late nineteenth century when the notion of “legit” was conceived, live public performances were more popular than they are today, when television, movies, the Internet, DVDs, and spectator sports provide so much competition for the stage. Even several decades into the twentieth century, other types of amusements, such as minstrel shows, vaudeville, burlesque (with and without strippers), magic shows, and musical revues often gathered bigger crowds than legitimate theater.

“Illegitimate” actors had a shady reputation, as most were itinerant barnstormers who swept in and out of small or medium-sized towns as third-rate carnivals do today. Their entertainments tended to be crude, with plenty of pantomime, caricature, low comedy, and vulgarity, so as to play to audiences of different educational levels, ethnicities, and even languages.

Cleverly, promoters of “legitimate” theater appealed to elite audiences, who could afford the relatively expensive tickets and understand the erudite language. Theater critics emerged well into the nineteenth century in the United States, trailing behind the British, who already featured theater reviewers in newspapers. The more affluent the base of the newspapers, the more critics would tend to separate the “mere” entertainments from the aesthetic peaks of serious theater.

These cultural cross currents are still in play today. Theater critics in New York bemoan the “dumbing down” of Broadway shows, Disney converting animated movies into theater pieces, and savvy producers casting “big name” television or movie stars in plays for their marquee value. And the stars are willing to take a drastic reduction in pay in order to have the status of legitimate theater bestowed upon them; they appear on talk shows and proclaim, “My roots are in theater.” We’ve yet to see a leading man coo to an interviewer: “My roots are in sitcoms.”

Not everyone takes these distinctions between “legit” and “illegit” so seriously. When Blue Man Group, with its roots in avant-garde theater, brought its troupe to the Luxor Hotel in Las Vegas, Chris Wink, cofounder of the Blue Man Group, proclaimed: “Now that Vegas has expanded its cultural palette and embraced Broadway-style legitimate theater, it feels like a good time to introduce some illegitimate theater.”

Submitted by Carol Dias of Lemoore, California.

M

ost major league baseball teams have the first baseman take custody of the ball that will be used for infield drills while their pitcher is warming up between half innings. When in the dugout while his team is at bat, the first baseman keeps the ball thrown to him in his glove.

One might expect that the catcher, the general of the infield, would be given this responsibility, but the catcher is saddled with one time-consuming fact of life alien to other infielders—in order to prepare to take the field, the catcher must don a mask, chest protector, and knee guards. The first baseman, who is the “catcher” of all the other infielders during the warm-up period (since the catcher is preoccupied with the pitcher), is thus given the not too heavy responsibility of tending to the ball and getting the infielders loosened up as soon as possible.