Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives (20 page)

Read Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives Online

Authors: Carolyn Steel

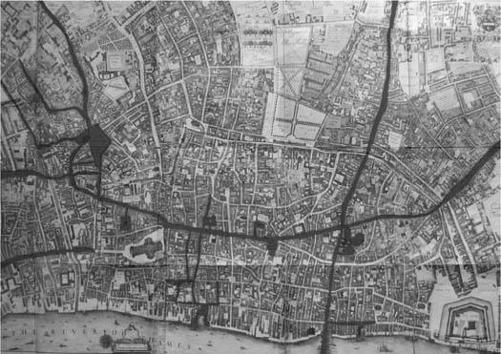

Look at the plan of any city built before the railways, and there you will be able to trace the influence of food. It is etched into the anatomy of every pre-industrial urban plan: all have markets at their heart, with roads leading to them like so many arteries carrying in the city’s lifeblood. London is no exception. The first measured survey of the capital, John Ogilby’s

Large and Accurate Map of the City of London

of 1676, shows just how closely the city mirrored the landscape that fed it. The plan is essentially that of the modern City: its Roman walls roughly semicircular in shape on the north bank of the Thames, with St Paul’s just west of centre and the Tower pinning down its south-east corner. Running through the middle is a single broad street, joining Newgate in the west to Aldgate in the east. The various names along this street – Cheapside, Poultry and Cornhill – confirm that this was London’s central food market (‘cheap’ is from the Old English

ceap

, to barter). At Cornhill it crosses another broad street running from north to south: the City’s other main axis leading over London Bridge.

Detail of Ogilby’s map, shaded to show food markets and supply routes.

A closer reading of the map reveals how food once reached the city. London’s sheep and cattle, many of them from Scotland, Wales and Ireland, approached from the north and west, streaming down the country lanes to Newgate, where the ancient city’s livestock market was held. During the ninth century, the market expanded to a ‘smooth field’ (Smithfield) just outside the city gate, where a meat market remains to this day. In its heyday, Smithfield dominated the neighbourhood, as George Dodd’s description of the ‘Great Day’, held annually in the week before Christmas, attests:

What a day was this! … On that day, 30,000 of the finest animals in the world were concentrated within an area of four or five acres. They had been pouring in from ten o’clock on the Sunday evening, insomuch that by daylight on the Monday they presented one dense animated mass, an agitated sea of brute life. All around the market, the animals encroached on space rightfully belonging to shopkeeping traffic; Giltspur Street, Duke Street, Long Lane, St John’s Street, King Street, Hosier Lane – all were invaded; for the cauldron of steaming animalism overflowed from very fullness.

14

Animals may no longer walk to Smithfield, but their memory lingers in its physical fabric. The names of local streets – Cowcross Street, Chick Lane, Cock Lane – recall a time when the area was full of living beasts, and St John’s Street, the chief route into the market from the north, is a broad, curving thoroughfare that still has something of the air of a country lane, its sweeping contours carved by the ‘sea of brute life’ that once flowed down it like a river.

Since London’s turkeys and geese came mainly from Suffolk and Norfolk (as many still do), they entered the city through Aldgate, having made the journey with specially protected cloth-wrapped feet.

Poultry, to the east of the city, is where they were bought and sold. Fruit and vegetables from Kent and Surrey were either sold at Borough Market or along Gracechurch Street, the road leading up from London Bridge to Leadenhall at the city’s main crossroads. Leadenhall was London’s first enclosed market, and still stands today on its historic site, near to the site of the ancient Roman forum. Such physical longevity is typical of markets everywhere – once established, they very rarely move. The river ports of Billingsgate and Queenhithe (originally owned, as we saw in the last chapter, by City and Crown) doubled as London’s main markets for fish and grain, as well as imported food. The streets leading up from the ports to Cheapside also became markets in their own right, as their names – Bread, Garlick and Fish Street – attest.

At first glance, London’s medieval plan may seem irrational, with its crooked streets, crowded spaces and lack of geometrical clarity. But seen through food, it makes perfect sense. Food shaped London, as it did every pre-industrial city, and as a way of engendering life and urban order, few things work half as well.

The presence of food in cities once caused chaos, but it was necessary chaos, as much a part of life as sleeping and breathing. Food was bought and sold openly in the streets, mainly so that authorities (such as the Parisian grain police) could keep an eye on proceedings. The principle of visibility meant that selling food indoors was prohibited in most medieval cities, which in turn meant that food shops as we know them now did not exist. Although houses facing on to markets were allowed to sell food, they had to do so over open boards, while their customers remained standing in the street. Most food was sold in the market, either from packs or barrels on the ground, or from portable trestles, set up and dismantled each day and stored in nearby houses. Market traders were granted pitches allowing them to sell certain foods in specific places and at set times, and were forbidden to wander about or sell their produce in any other way. Because of this, pitches were jealously guarded, and disputes over territory were common. In fifteenth-century

Padua, one quarrel between the city’s fruiterers and vegetable-sellers was only settled when the mayor himself intervened, marking a line on the ground with his own hand.

The space in which food could be sold in cities also had to be controlled in order to stop it from taking over the streets entirely, as this thirteenth-century London edict suggests:

All manner of victuals that are sold by persons in Chepe [Cheapside], upon Cornhill and elsewhere in the city, such as bread, cheese, poultry, fruit, hides and skins, onions and garlic, and all other small victuals, for sale as well by denizens as by strangers, shall stand midway between the kennels [gutters] of the streets, so as to be a nuisance to no-one, under pain of forfeiture of the article.

15

Since markets were often the only large public spaces in cities, most had to double as ceremonial spaces too. One contemporary sketch of Cheapside shows the market transformed to receive Marie de Medici.

16

A series of grandstands decked out with striped awnings and banners line the space, with rows of feather-hatted noblemen watching a seemingly endless procession of horse-drawn carriages, flanked by pike-bearing soldiers and drummers. The market’s half-timbered buildings serve as the peanut gallery, their windows crammed with faces, one to each leaded windowpane. The sketch demonstrates what a naturally theatrical space Cheapside was. Swap the ducks and geese for a few royal props, and hey presto: the market metamorphoses into a royal reception room. It is a pity (but typical) that no similar sketch exists of Cheapside in its ordinary, everyday use. Nobody ever thinks the mundane routines of their own day are worth recording.

Markets often represented cities on formal occasions, but at other times they were the place where the countryside came to town. Rome’s Piazza Montanara was one of the city’s liveliest markets until it was destroyed by Mussolini during his imperial makeover of the city in the 1930s. The piazza, which was on the site of the ancient city’s vegetable market, the Forum Holitorium, was the Sunday meeting place for

contadini

, country folk who walked through the

night to sell produce there, exchange labour, or use the services of the barbers, scribes and tooth-extractors who came each week to attend to their needs. At festival times, such rural invasions could take over the city completely. Many urban festivals were derived from country traditions in any case; and local peasants often chose to come to the city to celebrate them, giving the latter a changed, bucolic flavour. A group of English visitors to Prato in Tuscany for the Feast of Our Lady in 1605 remarked on the curious appearance of the large crowd gathered in the main piazza, ‘whereof we judged one half to have hats of straw and one fourth part to be bare-legged’.

17

The pivotal role played by markets in urban life made them inherently political. Two of the most famous public spaces in the world, the Roman Forum and the Athenian Agora, were both originally food markets, that gradually made the transition from commercial to political use as the cities they served grew in size. The pattern was to be repeated all over Europe: one only has to think of the number of town halls on market squares to understand the power of the relationship. Such urban set pieces were both highly practical and gave a clear symbolic expression of the civic order.

The thirteenth-century Palazzo della Ragione in Padua – affectionately known locally as

il Salone

– is one such arrangement. The building’s nickname refers to its council chamber, a vast first-floor hall with the largest vaulted wooden roof of its day, set over a series of arcades and shops. The vertical arrangement was necessary because the

Salone

was built right in the middle of the city’s market square, whose two halves thus had to be reunited beneath its belly. For centuries, representatives of the Paduan Commune gathered here to discuss matters of state, while the bustle of market life carried on below. Hall and market were a perfect reflection of the urban hierarchy: politics supported by commerce, and the mutual dependence of one upon the other. The

Salone

has dominated visual representations of Padua since it was built, looming out of prints like some benign whale beached in

the midst of the city. The architect Aldo Rossi called it an ‘urban artifact’, a civic monument so powerful that it held its meaning for the city long after its original use had ceased:

In particular, one is struck by the multiplicity of functions that a building of this type can contain over time and how these functions are entirely independent of the form. At the same time, it is precisely the form that impresses us; we live it and experience it, and in turn it structures the city.

18

What Rossi didn’t say is that much of the

Salone

’s power comes from its relationship with the market. Food is always getting overlooked in this way, not least by architects trained to think of space as something defined by bricks and mortar rather than by human actions. But space is also created by habit: the pitching of stalls in the same place day after day, multiple lifetimes of deals and nods, conversations and exchanges. Surviving records from the Paduan market suggest its space was delineated just as precisely as that of the

Salone

. One document from the fourteenth century lists the exact locations where one would go to buy wild game, birds and fish; piglets and cooked trotters; hay and horse fodder (horses need to eat too).

19

Another map from the eighteenth century shows how the positions of stalls for sea fish would change from summer to winter, a reminder that the use of the space, like the food it sold, changed with the seasons. Such spaces may be ephemeral, but they are no less powerful for that. They remind us that it is often the way in which spaces are inhabited that matters most, not just the physical boundaries that appear to define them.

A perfect example of this is the ancient Athenian Agora, arguably the most complex and radical public space the world has ever known, yet you wouldn’t have guessed so by looking at it. A large, irregular space, roughly diamond-shaped in plan and fringed on three sides by

stoas

(long, low buildings with open colonnades facing inwards) it contained numerous archaic monuments and shrines, and was cut in two by a road leading up to the city’s sacred compound, the Acropolis. The ground was made of packed earth, and there were clumps of plane trees here and there to provide shade. Food and other goods were sold from

trestles in the open air, and each type of produce had its own section, so that locals might say, ‘I went off to the wine, the olive oil, the pots’; or ‘I went around to the garlic and the onions and the incense, and straight on to the perfume.’

20

The Agora was generally held to be full of rascals, with fishmongers giving customers what the historian R.E. Wycherley called the ‘Greek equivalent of the Billingsgate’, a colourful stream of oath and invective designed to befuddle customers and disguise the fact that they were being sold rotten fish.

21

The Agora was also famous for its oratory. Socrates was a regular speaker, gathering large crowds to his favourite spot near the food-sellers and money-lenders, where he would hold forth on the topics of the day. There was always something going on in the Agora, and men and women often went there for an evening stroll, to visit the stalls and wine shops, listen to speakers, or just hang out. The word

agora

comes from the Greek verb

ageiro

, meaning ‘to gather’, and

agorazein

meant variously ‘to frequent the Agora’, ‘to buy in the marketplace’, or (best of all) ‘to haunt the Agora’. As its lexical complexity suggests, the Agora was much more than just a food market. It was a sacred precinct, a law court, a social space – as well as the seat of Athenian democracy. It was here, among the discarded grape pips and rotten fish heads, that Athenian citizens gathered to debate matters of state, making political decisions on the basis of on-the-spot public votes.

22