Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives (22 page)

Read Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives Online

Authors: Carolyn Steel

Popular unrest was never far from the surface in pre-industrial cities, often due to the unpredictability of the food supply, and markets were naturally the focus of such disturbances, not least because of their connection with food. In Paris the situation was made worse by the fact that the capital was fed almost entirely from a single central market, Les Halles. Whereas London markets were scattered all over the city and specialised in certain foods, Les Halles reflected Paris’s rationalised, centralised food supply. It was split into various quarters selling different kinds of produce, each presided over by its own dynastic clan, who married amongst themselves and kept a mafia-like grip on their respective trades. Dubbed

Le Ventre de Paris

(the belly of Paris) by Émile Zola, the market was a city within the city, with its own population, customs, rules, taverns – even its own clocks that showed the seasons as well as the time of day. As the

encyclopédiste

Denis Diderot noted, it also had its own opinions: ‘Listen to a blasphemy. La Bruyère and La Rochefoucauld are very ordinary and pedestrian books when one compares them to the wiles, the wit, the politics and the profound reasonings that are practised in a single market day at the Halle.’

37

Market traders, like taxi-drivers, have never been shy of expressing their views, and their closeness to food has always given them a ready audience. In

Ancien Régime

Paris, the frequent food shortages made Les Halles a hotbed of political ferment. It even had its own group of ringleaders, the

forts

, strongmen who acted as the market’s beasts of burden, doing the work of the official porters for a fraction of their wages. The

forts

were born fighters (many were part-time soldiers), and they delighted in stirring up trouble, spreading rumours of food shortages from the market into the surrounding streets. In the weeks leading up to the Revolution, they became natural leaders of the mob. The

forts

were beyond the control of the police, and, as with so many other aspects of the Parisian food supply, it was a problem of the latter’s own making. By concentrating all the city’s food in one place, they created a powerhouse strong enough to defy them.

Even in times of peace, food is never far removed from violence. Both are part of our animal natures, and when live beasts are present in the city, the relationship becomes explicit. The slaughter of animals in London remained unregulated until the surprisingly late date of 1848, by which time there were over 100 slaughterhouses in the Smithfield area alone, many of them in the ordinary basements of houses and butcher’s shops. The so-called ‘shambles’ were horrific places by all accounts, where the cattle were ‘killed and flayed in dark, confined and filthy cellars’.

38

The streets above were little better, to judge from one contemporary account: ‘Through the filthy lanes and alleys no one could pass without being butted with the dripping end of a quarter of beef, or smeared by the greasy carcasse of a newly-slain sheep. In many of the narrow lanes there was hardly room for two persons to pass abreast.’

39

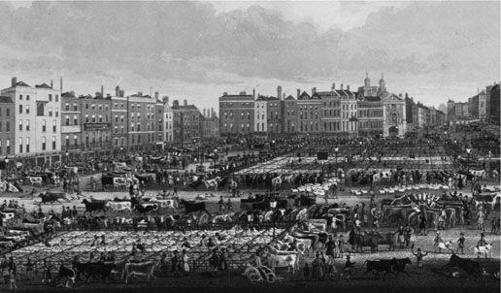

‘An agitated sea of brute life’. Smithfield Market, around 1830.

By Victorian times, such grotesque scenes were no longer acceptable. A growing distaste for animal cruelty led to a clamour for the market to be closed down – a move made possible for the first time by the arrival of the railways. The livestock market was shifted to specially built facilities in Islington in 1885, and Smithfield became the meat market it remains today. The moment the sight of animal slaughter became too much to bear, the railways came along and saved the day

– or perhaps it was the other way around. It is human nature to deal only with what we really have to.

Nobody could argue with the need to close Smithfield down; by the end it was overcrowded, cruel and unsanitary. But its removal cost London something too. For all their mess, noise and nuisance, markets bring something vital to a city: an awareness of what it takes to sustain life. They are what the French sociologist Michel Foucault called ‘heterotopias’: places that embrace every aspect of human existence simultaneously, that are capable of juxtaposing in a single space several aspects of life that are ‘in themselves incompatible’.

40

Markets are contradictory spaces, but that is the point. They are spaces made by food, and nothing embodies life quite like food does.

Well into the nineteenth century, markets remained the primary source of fresh food in cities all over Europe. However, London proved something of an exception. The authorities’ refusal to grant further market licences during the city’s rapid expansion in the seventeenth century (for fear of losing control) led to food shops springing up illegally. Before long, there were so many in the capital that their presence was tacitly accepted, and the city’s streetscape was duly transformed. Bowed shop windows began to appear, in Cheapside and elsewhere, along with large heavy shop signs, some of them so cumbersome that they were deemed a public danger and banned.

41

Many shops still served their customers through an open window, but as Georgian estates spread into the West End, new kinds of food stores opened in order to serve them. The age of the high street had arrived.

With the arrival of the railways, high streets began to replace markets as urban food hubs all over Britain. As cities spread, authorities had no choice but to relinquish the control they had once exercised over food trades. The industrialisation of the food supply made such controls appear unnecessary in any case. Butchers, bakers and grocers began to open in new suburban neighbourhoods, catering to their mainly middle-class residents. The new shops marked a radical shift in the way

food was bought and sold in cities. For the first time, significant numbers of the relatively well-off – the burgeoning middle-classes – were buying their own food. No less significantly, trade in food began to move from the public to the private realm.

The grocery trade did not get off to a very auspicious start. The new shops were the antithesis of the old adage that food should be sold transparently. Their interiors were cramped and dark, and most of the produce was stored in sacks or drawers under the counter. There was little advertising and items were not priced, so customers were forced to haggle for goods, something many were not used to. To make matters worse, there was little competition, so customers often had no choice of where to shop (modern occupants of Tescotowns will sympathise). Unsurprisingly, many grocers took advantage of the situation. Deliberate adulteration was rife, with traders mixing fine earth with cocoa powder to make it go further, alum with flour to make it whiter, or displaying fresh butter on the counter while serving customers from rancid stock below. As the opening verses of G.K. Chesterton’s ‘Song Against Grocers’ suggests, such practices became endemic to the grocery trade.

God made the wicked grocer

For a mystery and a sign,

That men might shun the awful shops

And go to inns to dine;

Where the bacon’s on the rafter

And the wine is in the wood,

And God that made good laughter

Has seen that they are good.

He sells us sands of Araby

As sugar for cash down;

He sweeps his shop and sells the dust

The purest salt in town,

He crams with cans of poisoned meat

Poor subjects of the King,

And when they die by thousands

Why he laughs like anything.

42

Perhaps it was no bad thing that the poor, who represented at least half the urban population of the time, did not frequent these early shops at all. Most still bought their food at weekly markets that specialised in selling cheap cuts and leftovers from regular markets, and were usually held in community halls on Saturday nights, when most workers’ pay packets came in.

In 1844, a group of Lancashire weavers decided that honest labourers deserved a better deal. Calling themselves the Equitable Pioneers of Rochdale, they banded together to form the world’s first retail co-operative, buying a limited range of goods (flour, butter, sugar and oatmeal) in bulk in order to get them cheaply, and selling them on to their fellow workers at fixed prices, splitting the profits at the end of the year as dividends. The shops were unlike any that had gone before. Every expense was spared in their decor: they had stark interiors bare of any furnishings, with food simply displayed on planks set on barrels or on the floor. But they were well lit, and the produce was clearly priced, much as it is in a modern supermarket. Since the shops were run by people who themselves worked during the day, they were only open in the evenings, but that didn’t stop them from becoming an overnight success. By the First World War, the co-operative movement had three million members in Britain, and a 15 per cent share of all food sales.

43

The idea of buying and selling in bulk was soon copied by shopkeepers with rather less socialist intentions. Among them was Thomas Lipton, who had spent much of his youth in America, and returned to his native Glasgow with a concept completely new to British food retail: advertising. When Lipton began selling eggs, bacon, butter and cheese to an unsuspecting public in 1871, he launched his shop with newspaper adverts and posters and a flurry of showmanlike stunts. He imported ‘the World’s Largest Cheese’ for Christmas, hauling it through the streets to the cheers of the crowd, and issued customers with the ‘Lipton £1’, for which they could buy £1 worth of goods in his shop for only 15 shillings.

44

The latter wheeze landed Lipton in court, but it was worth it. The additional custom it brought boosted his turnover to such an extent that he was able to undercut his rivals – the first step in his inexorable rise to building the world’s first global food empire. By 1900, Lipton had an international distribution network

serving hundreds of retail outlets, his own tea plantations in Ceylon, and 10,000 employees worldwide. Lipton’s Tea, which was sold far more cheaply than any before it, cornered the growing working-class market, and remains Lipton’s most visible legacy. However, it was his pioneering approach to retail, with his dedicated supply chain, own-brand products, loss-leading sales pitches and advertising campaigns, that made him the true pioneer of the modern grocery trade.

One innovation that eluded Lipton – one that was about to turn shops like his into supermarkets – was the concept of self-service. That was the contribution of Clarence Saunders, a flamboyant Memphis grocer who realised that one of his biggest overheads was the time spent by staff dealing with customers. At the start of the twentieth century, most Americans bought their food from homely ‘mom-and-pop’ stores, all-purpose family grocers that often acted as unofficial social centres for the local community. Saunders realised that if he could cut out the sociability of food shopping, he could reduce his prices to unbeatable levels. His self-service Piggly Wiggly store, opened in 1916, was the result. The Piggly Wiggly was essentially the world’s first supermarket, and, considering how many of its features were radically new, its resemblance to the modern version was remarkable. Customers entered through turnstiles, picked up wire baskets to carry round as they shopped, took food off shelves themselves, and queued up to pay for it at checkouts.

45

Today we take such behaviour for granted, but back in 1916 it was startlingly different. The store opened to a chorus of cynicism from Saunders’ competitors, but that soon changed to a stampede to copy his ideas when it became clear that, if food was cheap enough, customers couldn’t care less whether they had a cosy chat over the counter as they bought it. Saunders, who had seen this coming, had the foresight to patent his invention, and now made his fortune franchising it to his rivals. Soon, self-service stores were popping up all over America, not just on high streets, but on the edge-of-town sites that were their natural home.

When supermarkets first appeared on the suburban horizon in America, they were viewed with suspicion. Everything about them seemed alien – not least their soulless anonymity. But once word got out about how cheap their prices were, public caution melted away. Taking a leaf out of Thomas Lipton’s book, the new stores offered huge discounts for bulk purchases, and since most customers drove to them, they could load up with as many bargains as they liked. Motorised punters were the last piece of the food retail puzzle – the missing link that signalled the true arrival of supermarket shopping. From now on, the mom-and-pops wouldn’t stand a chance.