Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives (44 page)

Read Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives Online

Authors: Carolyn Steel

Despite the many similarities between Roman patterns of consumption and our own, there is one crucial difference. Rome had the luxury of an expanding world; we don’t. As it happens, Rome ran out of infrastructure before it ran out of food, but evidence suggests it was a close-run thing. To the inhabitants of late-eighteenth-century Britain, that was a sobering thought. The first nation in Europe to possess a capital comparable in size to Rome, the British were encountering food supply problems of a similar nature for the first time. Casting a mathematical eye over the swollen metropolises of his day, the English political economist Thomas Robert Malthus did a simple calculation, and came up with a gloomy prediction. In his 1798

Essay on the Principle of Population

, he argued that ‘population must always be kept down to the level of the means of subsistence’, and that since human populations increased geometrically, while agricultural outputs only did so arithmetically, mankind would eventually run out of available land, and was so doomed to run out of food. Only some reduction in numbers, through war, pestilence or voluntary ‘moral restraint’ could save man from this inevitable end.

The impact of Malthus’s pessimistic tract was widespread and profound. Among his many admirers was Charles Darwin, who later used Malthus’s ideas to help formulate his own theory of natural selection, applying it not just to mankind, but to all living creatures. But

not everyone was so impressed. Malthus’s critics, whose ranks swelled almost from the moment his ink dried, argued that he had left something essential out of the equation: mankind’s ingenuity. Man, they said, would not starve, because he would adapt, either by limiting his consumption for the common good, or by finding ways to increase agricultural yields. Since faith in artificial fertiliser was by no means universally shared (most notably not by its own inventor, Justus von Liebig), opinions differed as to quite how the latter was to be achieved. However, the cheery consensus was that somehow, man would be saved by his ability to think his way out of trouble.

Two centuries later, the debate continues. Malthus’s detractors and supporters have both scored victories since his day. The mass starvation he predicted for the mid nineteenth century never took place, thanks largely to monocultural grain production fuelled by artificial fertiliser; on the other hand, the world’s two most populous countries – India and China – have felt the need to adopt population-limiting policies aimed at effecting the same results as Malthus’s ‘moral restraint’. Opinions still differ over whether population control, technology or a new-found selflessness will save mankind. One thing, however, is clear. All that we have achieved by tearing up rainforests and dumping chemicals on the ground is to postpone the Malthusian question. What we have not done is make it go away.

Jeremy BenthamWe never exercise, or should never exercise a

besoin

as pure loss. It should be put to use as manure.

55

Of all bad habits, those to do with food can be the hardest to crack. The past is littered with examples of cities that one way or another have eaten themselves to death. Of course, civilisations fail for many reasons: lack of knowledge, climate change, shifting political allegiances, even sheer bad luck can spell their end. But as Jared Diamond argued in his recent book

Collapse

, it is often the choices people make in the light of

clear evidence that seal their fate – even when the facts that could have saved them were staring them in the face.

56

What makes the study of past civilisations so grimly fascinating is the discovery that the dilemmas we face are nothing new. The struggle to survive is part of the human condition, along with a certain blindness to its consequences. Unless you happen to have shares in agribusiness, the signs that our industrialised food systems are flawed – that we are well on the way to Malthusian meltdown – are about as unambiguous as you could get. Yet like so many civilisations before us, we fail to see the problem, because we have trained ourselves for centuries not to see it.

In the same way that other people’s doomed love affairs are easier to dissect than one’s own, we can talk endlessly about how the Romans got it wrong, without seeing the same faults in ourselves. But not even the all-consuming Romans were blind to the value of their waste.

Popinae

, as we saw, were cookshops that sold leftover meat from temples, and Roman agronomists were enthusiastic about the benefits of using night soil as fertiliser. But the most blatant use of waste was by the emperor Vespasian, who raised funds by imposing a tax on urine from public latrines. Suetonius reports that when the emperor’s son Titus complained that such a tax was not seemly, his father asked him to sniff the money to see whether it smelled bad. ‘

Pecunia non olet

’ – money does not smell – became Vespasian’s most famous axiom.

57

Even post-industrial cities have occasionally shown an enlightened attitude towards waste. Nineteenth-century Cincinnati, dubbed ‘Porkopolis’ as we saw due to its meat-packing activities, gave its hogs the freedom of the city, allowing them to roam about at will, while citizens were required by law to throw their food waste into the middle of the street to make it easier for the hogs to eat. As one English visitor remarked in 1832, ‘If I determined upon a walk up the main street, the chances were five hundred to one against my reaching the shady side without brushing by a snout fresh dripping from the kennel.’

58

Yet of all nineteenth-century cities, the one that really bucked the trend was Paris. Although Haussmann’s sewers purged the capital extremely effectively, the Seine did not flow strongly enough to carry the waste away, and for 45 miles downstream of the city it was a black and bubbling morass. The solution to this latest threat from ‘below’

would vindicate the pleadings of those such as Liebig and Chadwick who had argued in vain for the re-use of London’s waste. Their French counterpart was Pierre Leroux, a prominent social philosopher whose ‘circulus’ theory of 1834 was written in direct refutation of Malthus. In it, Leroux declared that since humans were producers as well as consumers, if they would only recycle their own waste, they need never run out of food. Leroux’s theory had long exposed him to ridicule in France, but while licking his wounds in exile in Jersey, he found a powerful convert in Victor Hugo, who became so convinced of Leroux’s arguments that he broke off from the narrative thread of

Les Misérables

to philosophise on the subject:

Do you know what all this is – the heaps of muck piled up on the streets during the night, the scavengers’ carts and the foetid flow of sludge that the pavement hides from you? It is the flowering meadow, green grass, marjoram, thyme and sage, the lowing of contented cattle in the evening, the scented hay and the golden wheat, the bread on your table and the warm blood in your veins – health and joy and life.

59

In 1867, five years after

Les Misérables

was published, the sanitary engineer A. Mille, already a convert to sewage filtration, persuaded his boss Eugène Belgrand to try it out in Paris. At an experimental farm at Clichy, Mille showed how irrigating the sandy soil with waste water not only filtered the water so effectively that it emerged purer than if it had been treated with chemicals, but rendered the land extremely fertile. Mille’s first experimental crop, consisting of 27 varieties of vegetable, had a market value six times greater than the grain previously grown on the site, and was of such high quality that it earned compliments at the 1867 Universal Exposition. The results delighted Chadwick, who had supported Mille’s experiments and defended him against those who objected to the idea of raising crops on sewage-enriched land:

An Academician pronounced it to be gross, and unfit for the food of cattle. I appealed from the judgment of the Academician to the

judgment of the cow on the point. A cow was selected, and sewaged and unsewaged grass was placed before it for its choice. It preferred the sewaged grass with avidity, and it yielded its final judgment in superior milk and butter of increased quantity.

60

Soon it was not only cows that approved of sewaged grass. With the discovery that porous sandy soil could both purify foul water and be made fertile in the process, political economists had found their philosopher’s stone. It seemed that shit really could be turned into gold. In 1869, Mille and his assistant Alfred Durand-Claye set up the world’s first municipal sewage treatment works at Gennevilliers, a sleepy little town across the river from Clichy. In order to overcome local resistance to the works, they offered 40 local farmers the chance to cultivate the irrigated land for nothing. By the following year, the engineers were inundated with requests from farmers for the right to irrigate their own land with sewage water. Results were so remarkable that Napoleon III felt compelled to make a visit to the sewage farm, arriving incognito, but leaving with armfuls of juicy vegetables. By 1900, there were 5,000 hectares of land under irrigation at Gennevilliers, each receiving 40,000 cubic metres of sewage water a day and capable of growing 40,000 heads of cabbage, 60,000 artichokes, or 200,000 pounds of sugar beet each per year. The water was used to soak the roots of crops, never touching their stems or leaves, and was found to be pure enough after filtration to be drawn off for domestic use. Gennevilliers was transformed from a one-horse town into Paris’s horticultural supplier of choice, with the city’s best hotels eager for its produce, and visitors coming out on day trips to marvel at the ‘veritable gardens of Eden’.

61

It is curious that Gennevilliers was the product of one of the most ruthless purges of any city in history – that the Haussmannisation of Paris should have demonstrated how the golden age of urban ecology could be replicated in the post-industrial era. Yet the fact that Paris’s circulatory experiment was the combined result of military strategy, sanitary reform and the accident of geography did not detract from its underlying message. Contemporary authorities in Berlin didn’t think so, anyway. In 1878, Berlin abandoned the chemical treatment of its waste in favour of sewage farms along Parisian lines. By the turn of the century, the city had 6,800 hectares of municipal farms under irrigation, with 3,000 farmers and their families living in rent-free cottages on them.

62

Contemporary commentators declared the farms to be a living vision of utopia. Some are still in use today, as an integral part of Berlin’s waste management and water purification systems.

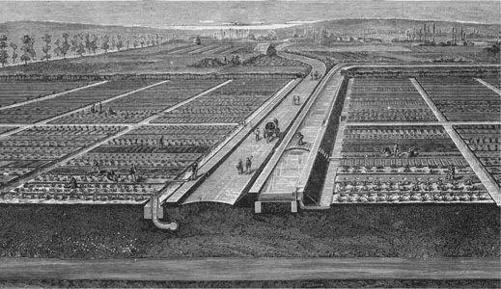

‘Veritable gardens of Eden.’ Gennevilliers in the 1870s.

Living in the urbanised West, the fact that the cities we inhabit are part of an organic continuum can be hard to grasp. Since we appear to live independently of nature, worrying about our waste can seem irrelevant; cranky, even. In Britain, we have never been overly fussed by the matter in any case. Food and raw materials have come too easily to us; and the sea has always been there to dump stuff into when we’re done with it. As a result, our throwaway culture is one of the most entrenched in Europe. In 2007, only Ireland and Greece sent more

waste per capita to landfill.

63

But however hard we try to ignore it, the issue of waste refuses to go away. Indeed, after a century or so of suppression, it is making a comeback in Western cities, threatening us once more with the danger of contamination ‘from below’. As a House of Commons Select Committee put it in 2007:

A little over ten years ago, 84 per cent of our municipal waste – the refuse councils collect from homes and businesses, parks and street bins – went to fill holes in the ground; a little over ten years from now, at present rates, there will, it is estimated, be no such holes left to fill.

64

We need to change our ways in Britain; not just because of the lack of holes, but to avoid punitive fines from the EU Landfill Directive, which from 2010 will impose stiff penalties on us if its targets are not met.

65

But as the days of chucking stuff into the ground draw to a close in Britain, we find ourselves caught between a rock and a mushy place. Unlike nineteenth-century Berliners, we Britons have neither the zeal nor the infrastructure for recycling. The introduction in 2006 of fortnightly bin collections – the government’s latest attempt to make us recycle more – simply caused widespread outrage, as the spectre of rat-infested, rotting garbage on the streets signalled a return to the horrors of the nineteenth-century city.