How to Live (29 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

If he could not watch a hare in pain, still less could he stomach the human tortures and judicial killings that were common in his day. “Even the executions of the law, however reasonable they may be, I cannot witness with a steady gaze.”

In his own career, he was expected to order such punishments, but he refused to do so. “I am so squeamish about hurting that for the service of reason itself I cannot do it. And when occasions have summoned me to sentencing criminals, I have tended to fall short of justice.”

He was not the only writer of his time to oppose either hunting or

torture. What is unusual in Montaigne is his reason for it: his visceral rapport with others. When speaking to the Brazilian Indians in Rouen, he was struck by how they spoke of men as halves of one another, wondering at the sight of rich Frenchmen gorging themselves while their “other halves” starved on their doorstep. For Montaigne, all humans share an element of their being, and so do all other living things. “It is one and the same nature that rolls its course.”

Even if animals were less similar to us than they are, we would still owe them a duty of fellow-feeling, simply because they are alive.

There is a certain respect, and a general duty of humanity, that attaches us not only to animals, who have life and feeling, but even to trees and plants.

We owe justice to men, and mercy and kindness to other creatures that may be capable of receiving it. There is some relationship between them and us, and some mutual obligation.

This obligation applies in trivial encounters as well as life-or-death ones. We owe other beings the countless small acts of kindness and empathy that Nietzsche would describe as “goodwill.” After the passage just quoted, Montaigne added this remark about his dog:

I am not afraid to admit that my nature is so tender, so childish, that I cannot well refuse my dog the play he offers me or asks of me outside the proper time.

He indulges his dog because he can imaginatively share the animal’s point of view: he can

feel

how desperate the dog is to banish boredom and get his human friend’s attention. Pascal mocked Montaigne for this, saying that Montaigne rides his horse as one who does not believe it to be his right to do so, and who wonders whether “the animal, on the contrary, ought really to be making use of him.”

This is exactly right—and, as much as it annoyed Pascal, it would have pleased Nietzsche, whose final mental breakdown is (unreliably) reported to have begun with his flinging his arms around a horse’s neck on a Turin street and bursting into tears.

Among less emotionally wrought readers, one much affected by

Montaigne’s remarks on cruelty was Virginia Woolf’s husband, Leonard Woolf.

In his memoirs, he held up Montaigne’s “On Cruelty” as a much more significant essay than people had realized. Montaigne, he wrote, was “the first person in the world to express this intense, personal horror of cruelty. He was, too, the first completely modern man.” The two were linked: Montaigne’s modernity resided precisely in his “intense awareness of and passionate interest in the individuality of himself and of all other human beings”—and nonhuman beings, too.

Even a pig or a mouse has, as Woolf put it, a feeling of being an “I” to itself. This was the very claim that Descartes had denied so strenuously, but Woolf arrived at it through personal experience rather than Cartesian reasoning. He recalled being asked, as a young boy, to drown some unwanted day-old puppies—an astonishing task to give to a child, one might think. He did what he was told, but was more upset by it than he had expected. Years later, he wrote:

Looked at casually, day-old puppies are little, blind, squirming, undifferentiated objects or things. I put one of them in the bucket of water, and instantly an extraordinary, a terrible thing happened. This blind, amorphous thing began to fight desperately for its life, struggling, beating the water with its paws. I suddenly saw that it was an individual, that like me it was an “I,” that in its bucket of water it was experiencing what I would experience and fighting death, as I would fight death if I were drowning in the multitudinous seas. It was I felt and feel a horrible, an uncivilized thing to drown that “I” in a bucket of water.

What brought this incident back to Woolf, as an adult, was reading Montaigne. He went on to apply the insight to politics, reflecting especially on his memory of the 1930s, when the world seemed about to sink into a barbarism that made no room for this small individual self. On a global scale, no single creature can be of much importance, he wrote, yet in another way these I’s are the

only

things of importance. And only a politics that recognizes them can offer hope for the future.

Writing about consciousness, the psychologist William James had a

similar instinct.

We understand nothing of a dog’s experience: of “the rapture of bones under hedges, or smells of trees and lamp-posts.” They understand nothing of ours, when for example they watch us stare interminably at the pages of a book. Yet both states of consciousness share a certain quality: the “zest” or “tingle” which comes when one is completely absorbed in what one is doing. This tingle should enable us to recognize each other’s similarity even when the objects of our interest are different. Recognition, in turn, should lead to kindness. Forgetting this similarity is the worst political error, as well as the worst personal and moral one.

In the view of William James, as of Leonard Woolf and Montaigne, we do not live immured in our separate perspectives, like Descartes in his room. We live porously and sociably. We can glide out of our own minds, if only for a few moments, in order to occupy another being’s point of view. This ability is the real meaning of “Be convivial,” this chapter’s answer to the question of how to live, and the best hope for civilization.

IT ALL DEPENDS ON YOUR POINT OF VIEW

T

HE ART OF

seeing things from the perspective of another person or animal may come instinctively to some, but it can also be cultivated. Novelists do it all the time. While Leonard Woolf was thinking through his political philosophy, his wife Virginia was writing in her diary:

I remember lying on the side of a hollow, waiting for L[eonard] to come & mushroom, & seeing a red hare loping up the side & thinking suddenly “This is Earth life.”

I seemed to see how earthy it all was, & I myself an evolved kind of hare; as if a moon-visitor saw me.

This eerie, almost hallucinatory moment gave Woolf a sense of how both she and the hare would look to someone who did not view them through eyes dulled by habit. It enabled her to de-familiarize the familiar—a mental trick, rather like those used by the Hellenistic philosophers when they imagined looking down on human life from the stars. Like many such tricks, it works by helping one pay proper attention. Habit makes everything look bland; it is sleep-inducing. Jumping to a different perspective is a way of waking oneself up again. Montaigne loved this trick, and used it constantly in his writing.

His favorite device was simply to run through lists of wildly divergent customs from all over the world, marveling at their randomness and strangeness.

His two essays “Of Custom” and “Of Ancient Customs” describe countries where women piss standing and men squatting, where children are nursed for up to twelve years, where it is considered fatal to nurse a baby on its first day, where hair grows on the right side of the body but is shaved completely off the left side, where one is supposed to kill one’s father at a certain age, where people wipe their rears with a sponge on a stick, and where hair is worn long in front and short behind instead of the other way

around. Similar lists in the “Apology” run from Peruvians who elongate their ears to Orientals who blacken their teeth because they consider white ones inelegant.

Each culture, in doing these things, takes itself as the standard. If you live in a country where teeth are blackened, it seems obvious that ebony ivories are the only beautiful ones. Reciting diversities helps us to break free of this, if only for brief moments of enlightenment. “This great world,” writes Montaigne, “is the mirror in which we must look at ourselves to recognize ourselves from the proper angle.”

After running through such a list, we look back upon our own existence differently. Our eyes are opened to the truth that our customs are no less weird than anyone else’s.

Some of Montaigne’s initial interest in such leaps of perspective went back to his observation of the Tupinambá visitors’ amazement in Rouen. Watching them watching the French was an awakening, like Virginia Woolf’s on the hillside. The encounter stimulated in Montaigne what became a lifelong interest in the New World—an entire hemisphere unknown to Europeans until a few decades before his own birth, and still so surprising that it hardly seemed real.

By the time Montaigne was born, most Europeans had come around to the acceptance that America really did exist and was not a fantasy. Some people had taken up eating hot peppers and chocolate, and a few smoked tobacco. The cultivation of potatoes was under way, although their vaguely testicular shape still made people think they were good only as an aphrodisiac.

Returning travelers passed on tales of cannibalism and human sacrifice, or of fabulous fortunes in gold and silver. As life in Europe became more difficult, many considered emigrating, and colonies sprouted like mold spores along the eastern coasts. Most were Spanish, but the French also tried their luck. In Montaigne’s youth, France looked well placed to prosper in the new colonial adventure.

It had a strong fleet, and well-equipped international ports from which to sail—Bordeaux foremost among them.

Several French expeditions were launched in the middle of the century, but they ran into difficulties one by one. French colonists had a particular tendency to undo their enterprises through religious conflict, which they imported with them. The first French settlement in Brazil, founded by

Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon near the present site of Rio de Janeiro in the 1550s, was so weakened by its Catholic–Protestant divisions that it succumbed to invasion by the Portuguese. In the 1560s, a mainly Protestant French colony in Florida fell victim to the Spanish. By this time, full civil war had broken out in the French homeland, and the money and organization for major voyages were hard to find. France missed its place in the first great bonanza overseas, the one that made the fortunes of England and Spain. By the time it recovered and tried again later, it was too late to recover the advantage in full.

Like many of his generation, Montaigne had a fascination with all things American combined with cynicism about colonial conquest.

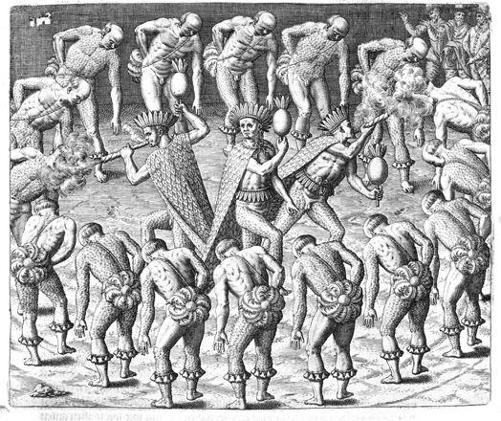

He treasured what he remembered of his conversation with the Tupinambá—who had traveled to France in one of Villegaignon’s returning ships—and collected South American memorabilia for his cabinet of curiosities in the tower: “specimens of their beds, of their ropes, of their wooden swords, and the bracelets with which they cover their wrists in combats, and of the big canes, open at one end, by whose sound they keep time in their dances.” Much of this probably came from a household servant who had lived for a time in the Villegaignon colony. The same man introduced Montaigne to sailors and merchants who could further feed his curiosity.

He was himself “a simple, crude fellow,” but Montaigne believed this made him an excellent witness, for he was not tempted to embroider or overinterpret what he reported.

Besides conversation, Montaigne also read everything he could get hold of on the subject. His library included French translations of López de Gómara’s

Historia de las Indias

and Bartolomé de Las Casas’s

Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias

, as well as more recent French originals, notably two great rival accounts of the Villegaignon colony by the Protestant Jean de Léry and the Catholic André Thevet. Of the two, he much preferred Léry’s

Histoire d’un voyage fait en la terre du Brésil

(1578), which observed Tupinambá society with sympathy and precision. As befitted a Protestant puritan, Léry admired the Tupinambá preference for going naked rather than adorning themselves with ruffs and furbelows as the French did. He observed that very few of their elderly people had white hair, and suspected it was because they did not wear themselves out with “mistrust, avarice,

litigation, and squabbles.” And he thought highly of their courage in war. The Tupinambá fought bloody battles with magnificent swords, but only for honor, never for conquest or greed. Such encounters usually ended with a feast at which the main course was prisoners of war. Léry himself attended one such event; that night he woke in his hammock to see a man looming over him brandishing a roasted human foot in what seemed to be a threatening manner. He leaped up in fright, to the merriment of the crowd. Later, it was explained to him that the man was only being a generous host and offering him a taste. Léry’s faith in his friends was restored. He felt safer among them, he said, than he did at home “among disloyal and degenerate Frenchmen.” Indeed, he was destined to witness equally gruesome scenes in the French civil wars, when he became stranded in the hilltop town of Sancerre during a winter siege at the end of 1572 and saw townspeople eating human flesh to survive.

Montaigne read Léry avidly, and, in writing up his own Tupinambá encounter in “Of Cannibals,” followed Léry’s practice of drawing out the

contrast with France and the implications for European assumptions of superiority. A later chapter, “Of Coaches,” also noted how the gilded gardens and palaces of the Incas and Aztecs put European equivalents to shame.

But the simple Tupinambá appealed to Montaigne far more. He described them with a list of desirable negatives: