How to Live (33 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

buried alive in heaps of manure, thrown into wells and ditches and left to die, howling like dogs; they had been nailed in boxes without air, walled up in towers without food, and garroted upon trees in the depths of the mountains and forests; they had been stretched in front of fires, their feet fricasseed in grease; their women had been raped and those who were pregnant had been aborted; their children had been kidnapped and ransomed, or even roasted alive before the parents.

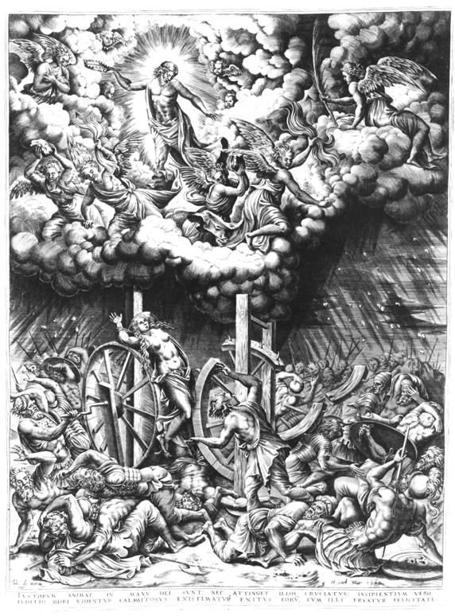

The wars were fed by religious ardor, but the sufferings of war in turn generated further apocalyptic imaginings. Both Catholics and Protestants thought that events were approaching a point beyond which there could be no more normal history, for all that remained was the final confrontation between God and the Devil. This is why Catholics celebrated the St. Bartholomew’s massacres so joyfully: they saw them as a genuine victory over evil, and as a way of driving countless misled individuals back to the true Church before it was too late for them to save their souls.

It all mattered a great deal, because time was short. In the Last Days, Christ would return, the world would be obliterated, and everyone would have to justify his or her actions to God. There could be no compromise in such a situation, no seeing the other person’s point of view, and certainly no mutual understanding between rival faiths. Montaigne, with his praise of ordinary life and of mediocrity, was selling something that could have no market in a doomed world.

Signs of the imminence of this Apocalypse were plentiful.

A series of famines, ruined harvests, and freezing winters in the 1570s and 1580s indicated that God Himself was withdrawing His warmth from the earth. Smallpox, typhus, and whooping cough swept through the country, as well as the worst disease of all: the plague. All four Horsemen of the Apocalypse seemed to have been unleashed: pestilence, war, famine, and death. A werewolf roamed the country, conjoined twins were born in Paris, and a new star—a nova—exploded in the sky. Even those not given to religious extremism had a feeling that everything was speeding towards some indefinable end. Montaigne’s editor, Marie de Gournay, later remembered the France of her youth as a place so abandoned to chaos “that one was led to expect a final ruin, rather than a restoration, of the state.” Some thought the end was very nigh indeed: the linguist and theologian Guillaume Postel wrote in a letter of 1573 that “within eight days the people will perish.”

The Devil, too, knew that his time of influence on earth was drawing to a close, so he sent armies of demons to win the last few vulnerable souls.

They were armies indeed. Jean Wier, in his

De praestigis daemonum

(1564), had calculated that at least 7,409,127 demons were working for Lucifer, under the middle-management of seventy-nine demon-princes. Alongside them were witches: a dramatic rise in witchcraft cases after the 1560s provided more proof that the Apocalypse was coming. As fast as they were detected, the courts burned them, but the Devil replaced them even faster.

Contemporary demonologist Jean Bodin argued that, in crisis conditions such as these, standards of evidence must be lowered. Witchcraft was so serious, and so hard to detect using normal methods of proof, that society could not afford to adhere too much to “legal tidiness and normal procedures.” Public rumor could be considered “almost infallible”: if everyone in a village said that a particular woman was a witch, that was sufficient to justify putting her to the torture. Medieval techniques were revived specifically for such cases, including “swimming” suspects to see if they floated, and searing them with red-hot irons. The numbers of convicted witches kept rising as standards of evidence went down, and the increase amounted to further proof that the crisis was real and that further adjustment of the law was necessary. As history has repeatedly suggested, nothing is more effective for demolishing traditional legal protections than the combined claims that a crime is uniquely dangerous, and that those behind it have exceptional powers of resistance. It was all accepted with hardly a murmur, except by a few writers such as Montaigne, who pointed out that torture was useless for getting at the truth since people will say anything to stop the pain—and that, besides, it was “putting a very high price on one’s conjectures” to have someone roasted alive on their account.

A major development warned of by the theologians was the imminent

arrival of the Antichrist.

Signs would abound in coming years: in 1583 an old woman in an African country gave birth to an infant with cat’s teeth who announced, in an adult voice, that it was the Messiah. Simultaneously, in Babylon, a mountain burst open to reveal a buried column on which was written in Hebrew: “The hour of my nativity is come.” The leading French expert on such Antichrist tales was Montaigne’s successor in the Bordeaux

parlement

, Florimond de Raemond, also an enthusiastic witch-burner. Raemond’s work

L’Antichrist

analyzed portents in the sky, the withering of vegetation and harvests, population movements, and cases of atrocity and cannibalism in the wars, showing how all proved that the Devil was on his way.

To join in mass violence, in such circumstances, was to let God know that you stood with Him. Both Protestant and Catholic extremists made a cult of holy zeal, which amounted to a total gift of yourself to God and a rejection of the things of this world.

Anyone who still paid attention to everyday affairs at such a time might be suspected of moral weakness, at best, and allegiance to the Devil at worst.

In reality, many people did carry on with their lives and keep out of trouble as best they could, remaining faithful to the ordinariness which Montaigne thought was the essence of wisdom. Even if they believed in it, the coming confrontation between Satan and God interested them no more than the scandals and diplomacy of the royal court. Many Protestants quietly renounced their faith after 1572, or at least concealed it, an implicit admission that they considered the life of this world more important than their belief in the next. But a minority went to the opposite extreme. Radicalized beyond measure, they called for total war against Catholicism and the death of the king—the “tyrant” responsible for the deaths of Coligny and all the other victims. It was in this context that La Boétie’s

On Voluntary Servitude

was suddenly taken up and published by Huguenot radicals, who reinvented it as propaganda for a cause La Boétie himself would never have favored.

As it turned out, regicide was unnecessary. Charles IX died of natural causes a year and a half later, on May 30, 1574. The throne passed to another of Catherine de’ Medici’s sons, Henri III, who proved even more unpopular. He was not even liked by many Catholics. Support grew

throughout the 1570s for the Catholic extremists known as

Ligueurs

or Leaguists, who would cause the monarchy at least as much trouble as the Huguenots in coming years, under the leadership of the powerful and ambitious duc de Guise. From now on, the wars in France would be a three-way affair, with the monarchy often caught in the weakest position. Henri tried occasionally to take over leadership of the Leagues himself, to neutralize their threat, but they rejected him, and often portrayed him as a Satanic agent in disguise.

He may have been too moderate for the Leagues, but Henri III was extremist in other ways, showing no understanding of Montaigne’s sense of moderation.

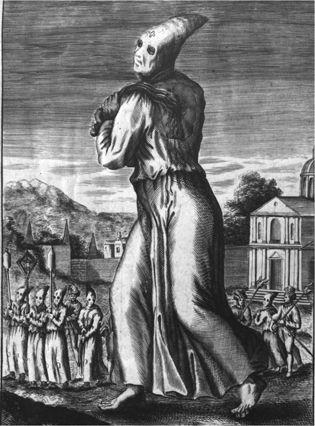

Montaigne, who met him several times, did not like him much. On the one hand, Henri filled his court with fops, and turned it into a realm of corruption, luxury, and absurd points of etiquette. He went out dancing every night and, in youth, wore robes and doublets of mulberry satin, with coral bracelets and cloaks slashed to ribbons. He started a fashion for shirts with four sleeves, two for use and two trailing behind like wings. Some of his other affectations were considered even stranger: he used forks at table

instead of knives and fingers, he wore nightclothes to bed, and he washed his hair from time to time. On the other hand, Henri also put on exaggerated displays of mysticism and penitence. The more perplexed he became by the problems facing the kingdom, the more frequently he took part in processions of flagellants, trudging with them barefoot over cobbled streets, chanting psalms and scourging himself.

To Montaigne, the notion that the solution to the political crisis could lie in prayer and extreme spiritual exercises made no sense.

He recoiled from these processions, and put no credence in comets, freak hailstorms, monstrous births, or any of the other signs of doom. He observed that those who made predictions from such phenomena usually kept them vague, so that later they could claim success whatever happened. Most reports of witchcraft seemed to Montaigne to be the effects of human imagination, not of Satanic activity.

In general, he preferred to stick to his motto: “I suspend judgment.”

His Skepticism drew some mild criticism; two contemporaries in Bordeaux, Martin-Antoine del Rio and Pierre de Lancre, warned him that it

was theologically dangerous to explain apocalyptic events in terms of the human imagination, because it distracted attention from the real threat. On the whole, he managed to avoid serious suspicions, but Montaigne did risk his reputation by speaking out against torture and witch trials. He was already associated in many people’s minds with a category of thinkers known to their enemies as

politiques

, who were distinguished by their belief that the kingdom’s problems had nothing to do with the Antichrist or the End Times, but were merely political.

They deduced that the solution should be political too—hence the nickname. In theory, they supported the king, believing that the one hope for France was unity under a legitimate monarch, though most of them secretly hoped that a more inspiring, more

unifying

king than Henri III might one day come along. While remaining loyal, they worked to find points of common ground between the other parties, in the hope of halting the wars and laying a foundation for France’s future.

Unfortunately, the one piece of common ground that really brought extreme Catholics close to extreme Protestants was hatred of

politiques

. The word itself was an accusation of godlessness. These were people who paid attention only to political solutions, not to the state of their souls. They were men of masks: deceivers, like Satan himself. “He wears the skin of a lamb,” wrote one contemporary of a typical

politique

, “but nevertheless is a raging wolf.” Unlike real Protestants, they tried to pass as something they were not, and, since they were so clever and intellectual, they did not have the excuse of being innocent victims of the Devil’s deception. Montaigne’s association with the

politiques

gave him a good reason to emphasize his openness and honesty, as well as his Catholic orthodoxy (though, of course, claiming to be honest is exactly what a wolf in sheep’s clothing would do).