How to Live (30 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

This is a nation … in which there is no sort of traffic, no knowledge of letters, no science of numbers, no name for a magistrate or for political superiority, no custom of servitude, no riches or poverty, no contracts, no successions, no partitions, no occupations but leisure ones, no care for any but common kinship, no clothes, no agriculture, no metal, no use of wine or wheat.

The very words that signify lying, treachery, dissimulation, avarice, envy, belittling, pardon—unheard of.

Such “negative enumeration” was a well-established rhetorical device in classical literature, long predating the New World encounter. It even turns up in four-thousand-year-old Sumerian cuneiform texts:

Once upon a time, there was no snake

, there was no scorpion,

There was no hyena, there was no lion,

There was no wild dog, no wolf,

There was no fear, no terror,

Man had no rival.

It was only natural that it should recur in Renaissance writing about the New World. The tradition would continue: in the nineteenth century Herman Melville described the happy valley of Typee in the Marquesas as a place where there were “no foreclosures of mortgages, no protested notes, no bills payable, no debts of honor … no poor relations … no destitute widows … no beggars; no debtors’ prisons; no proud and hard-hearted nabobs in Typee; or to sum up all in one word—no money!”

The idea was that people were happier when they lived uncluttered lives close to nature, like Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Stoics had made much of this “Golden Age” fantasy: Seneca fantasized about a world in which property was not hoarded, weapons were not used for violence, and no sewage pipes

polluted the streams.

Without houses, people even slept better, for there were no creaking timbers to wake them with a start in the middle of the night.

Montaigne understood the appeal of the fantasy, and shared it. Like wild fruit, he wrote, wild people retain their full natural flavor.

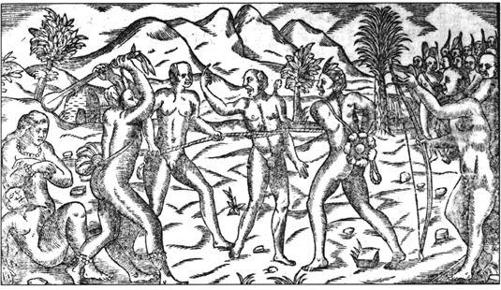

This was why they were capable of such bravery, for their behavior in war was untainted by greed. Even the Tupinambá cannibal rituals, far from being degrading, showed primitive people at their best.

The victims displayed astonishing courage as they awaited their fate; they even defied their captors with taunts of their own. Montaigne was impressed by a song in which a doomed prisoner challenges his enemies to go ahead and eat their fill. As you do, sings the prisoner, remember that you are eating your own fathers and grandfathers. I have eaten them in the past, so it will be

your

flesh you will savor! This is another of those archetypal confrontation scenes: the defeated man is doomed, yet he shows Stoic firmness in the face of his enemy. This, it is implied, is what humans would always be capable of if they only followed their true nature.

The prisoner’s song is one of two “cannibal songs” to appear in Montaigne’s

Essays

. The other, also from the Tupinambá, is a love lyric which he may have heard performed in Rouen in 1562, for he praises the sound of it: he describes Tupinambá as “a soft language, with an agreeable

sound, somewhat like Greek in its endings.” In his prose translation, the song goes:

Adder, stay; stay, adder, that from the pattern of your coloring my sister may draw the fashion and the workmanship of a rich girdle that I may give to my love; so may your beauty and your pattern be forever preferred to all other serpents.

Montaigne liked the simple elegance of this, by contrast with the over-refined European versifying of his day. In another essay, he wrote that such “purely natural poetry”—among which he counted the traditional villanelles of his own Guyenne as well as the songs brought back from the New World—rivaled the finest found in books. Even the classical poets could not compete.

Montaigne’s “cannibal love song” went on to have an impressive little afterlife of its own, independent of the rest of the

Essays

. Chateaubriand borrowed it for his

Mémoires d’outre-tombe

, where he had an attractive North American girl sing something similar. It then migrated to Germany, where it flourished as a

Lied

throughout the eighteenth century—this in a country which otherwise took little early interest in Montaigne. The two cannibal songs, together with some complimentary remarks about German stoves, were the only fragments of Montaignalia to make much impact at all in that part of the world until Nietzsche’s time. “Adder, Stay” was translated by some of the best German Romantic poets: Ewald Christian von Kleist, Johann Gottfried Herder, and the great Johann Wolfgang von Goethe himself—who produced both a

Liebeslied eines Amerikanischen Wilden

(“Love Song of an American Savage”) and a

Todeslied eines Gefangenen

(“Death Song of a Prisoner”). German Romantics especially favored songs about love and death, so it is not surprising that they took so eagerly to Montaigne’s transcriptions. What is striking is that they seized them from the text while ignoring almost everything else—but this is what all readers do, to a greater or lesser extent.

Montaigne, like Léry, could be accused of romanticizing the peoples of the New World. But he understood too much about the complexity of human psychology to really want to wipe half of it out in order to live like

wild fruit. He also recognized that American cultures could be just as stupid and cruel as European ones. Since cruelty was the vice he deplored most, it is significant that he made no attempt to gloss over its role in New World religions, some of which were bloodthirsty indeed. “They burn the victims alive, and take them out of the brazier half roasted to tear their entrails out.

Others, even women, are flayed alive, and with their bloody skins they dress and disguise others.”

He described such atrocities, but then pointed out that they seemed excessive mainly because Europeans were unfamiliar with them. Equally terrible practices were accepted nearer home, because of the power of habit. “I am not sorry that we notice the barbarous horror of such acts,” he wrote of the New World sacrifices, “but I am heartily sorry that, judging their faults rightly, we should be so blind to our own.”

Montaigne wanted his readers to open their eyes and

see

. The peoples of South America were not just fascinating for their own sake. They made an ideal mirror, in which Montaigne and his countrymen could “recognize themselves from the proper angle,” and which woke them out of their self-satisfied dream.

Eighteenth-century German readers may have found little of interest in Montaigne other than his

Volkslieder

, but a new generation of French readers rediscovering him in the same period made more of his cannibals and mirrors than even Montaigne himself could have anticipated.

They were encouraged in this by a sleek modern edition which appeared in 1724. The

Essays

were still outlawed in France—it had been fifty years since the ban—but now the country began receiving a stream of smuggled Montaigne texts from England, where the French Protestant exile Pierre Coste had put together an edition for the new century.

Coste deliberately brought out Montaigne’s subversive side, not by interfering with the text but by adding extra paraphernalia, most dramatically La Boétie’s

On Voluntary Servitude

, which he included in full with the edition of 1727. This was the first time the

Voluntary Servitude

had been published at all since the Protestant tracts of the sixteenth century, and certainly the first time it had

appeared joined to the

Essays

. It altered Montaigne by association, and gave him the aura of a political and personal rebel, the sort of writer whose calm philosophy might conceal more turbulent meanings. Coste helped to create a version of Montaigne still popular today: a secret radical, who conceals himself under a veil of discretion. In particular, Coste’s edition made Montaigne look like a free-thinking Enlightenment

philosophe

born two centuries too early. Eighteenth-century readers recognized themselves in him, as so many do, and they felt amazed that he had needed to wait so long before meeting the generation truly capable of understanding him.

This new breed of “enlightened” reader responded passionately to his portrayal of the courageous Tupinambá. Montaigne’s cannibal Stoics aligned themselved with a new fantasy figure: that of the noble savage, an impossibly perfect being who united primitive simplicity with classical heroism, and who now became the object of a cult. Adherents of the cult kept hold of Montaigne’s sense that cannibals had their own sense of honor, and that they held up a mirror to European civilization. What they lost was Montaigne’s understanding that “savages” were also as flawed, cruel, and barbarous as anyone else.

Among the writers to fall upon Montaigne’s Tupinambá with delight was Denis Diderot, a philosopher who became famous for his contributions to the era’s monumental compilation of knowledge, the

Encyclopédie

, as well as for countless philosophical novels and dialogues.

Diderot read Montaigne early in his career, loved him, and paid him the compliment of quoting the

Essays

in his own writings—usually, but not always, with due credit. In his short

Supplément au voyage de Bougainville

, of 1796, Diderot wrote excitedly about the peoples of the South Pacific, recently encountered by Europeans, and thus his century’s equivalent to native Americans in Montaigne’s time. Like the Tupinambá, Pacific islanders seemed to lead a simple life, almost in a state of grace. Less palatable aspects of their culture were easy to ignore, because Europe knew little about them. This left plenty of room to make things up, notably the idea that the islanders enjoyed hedonistic sex with anyone they liked at any time. In the

Supplément

, Diderot had one of his Tahitian characters advise Europeans that they need only follow nature to be happy, for no other law applied. This was what his compatriots wanted to hear.

The noble savage was raised to a more exalted level by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, another writer influenced by Montaigne—his annotated copy of the

Essays

survives.

Unlike Diderot, Rousseau took primitive society to be something so perfect that it could not actually exist in any real part of the world, not even the Pacific. It functioned only as an ideal contrast to the mess that real societies had become. By definition, all existing civilization was corrupt.

In his

Discourse on the Origin of Inequality

, Rousseau imagines what man might have been like without the chains of civilization. “I see an animal … eating his fill under an oak tree, quenching his thirst at the first stream, making his bed at the base of the same tree that supplied his meal.” The earth gives this natural man everything he needs. It does not pamper him, but he needs no pampering. Harsh conditions from infancy have made him resistant to illness, and he is strong enough to fight off wild beasts unarmed. He has no axes, but he uses his muscles to break thick branches unaided. He has no slingshots or guns, but he can throw a stone powerfully enough to bring down any prey. He needs no horses, for he can run as fast as one. Only when civilization makes man “sociable and a slave” does he lose his manliness, learning to be weak and to fear everything around him. He also learns despair: no one ever heard of a “free savage” killing himself, says Rousseau. He even loses his natural tendency to be compassionate. If someone slits a person’s throat under a philosopher’s window, the philosopher is likely to put his hands over his ears and pretend not to hear; a savage would never do this. A natural man could not fail to heed the voice within that makes him identify with his fellows—a voice that sounds very much like the one which calls Montaigne to feel sympathy for all suffering fellow beings.

If one reverses chronology and imagines Montaigne settling down in his armchair to read Rousseau, it is intriguing to wonder how far he would have followed this before tossing the book from him. In the early stages of this passage, he might have felt enchanted; here was a writer with whom he was in perfect harmony. A few paragraphs later, one imagines him faltering and frowning. “Though I don’t know …” he might murmur, as the wave of Rousseau’s rhetoric keeps swelling. Montaigne would want to pause and examine it all from alternative angles. Does society really make us callous? he would ask. Are we not better in company? Is man really born free; is he

not filled with weaknesses and imperfections from the start? Do sociability and slavery go together? And by the way, could anyone really throw a stone powerfully enough to kill something at a distance without a slingshot?

Rousseau never stops or reverses direction.

He sweeps along, and sweeps many readers with him too: he became the most popular author of his day. Reading a few pages of Rousseau makes one realize just how different he is from Montaigne, even when the latter seems to have been a source for his ideas. Montaigne is saved from flights of primitivist fantasy by his tendency to step aside from whatever he says even as he is saying it. His “though I don’t know” always intervenes. Moreover, his overall purpose is different from Rousseau’s. He does not want to show that modern civilization is corrupt, but that all human

perspectives

on the world are corrupt and partial by nature. This applies to the Tupinambá visitors, gazing at the French in Rouen, just as much as to Léry or Thevet in Brazil. The only hope of emerging from the fog of misinterpretation is to remain alert to its existence: that is, to become wise at one’s own expense. But even this only provides an imperfect solution. We can never escape our limitations altogether.