Henry V: The Background, Strategies, Tactics and Battlefield Experiences of the Greatest Commanders of History Paperback (11 page)

Authors: Marcus Cowper

Tags: #Military History - Medieval

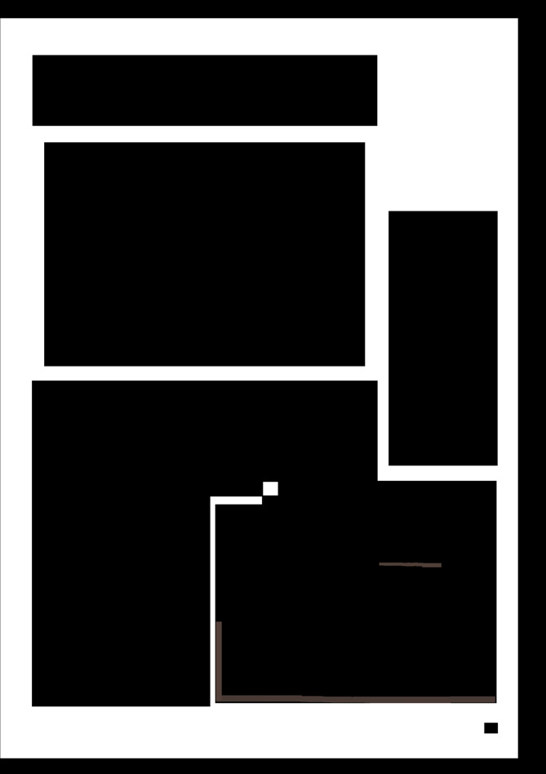

The battle of Agincourt, 25 October 1415

French Camp .

w W f> W.^v

kiS&fjfc&XffiiS

m&mkm

. English Camp

English Forces

1. Dismounted men-at-arms under King Henry

2. Dismounted men-at-arms under Thomas Lord Camoys

Maisoncelle ^ ^

3. Dismounted men-at-arms under the Duke of York

4. Archers on the flanks

French Forces

A. Dismounted men-at-arms under Charles d'Albret

B. Cavalry commanded by the Count of Vendome

C. Cavalry commanded by Clignet de Brebant

D. Second line of dismounted men-at-arms along with archers

and crossbowmen, commanded by the Dukes of Bar and Alengon

E. French calvary

as opposed to men-at-arms, while the French forces were much more

traditionally based upon the heavily armoured men-at-arms as the centre

point of their fighting force.

The French system of command and control was by no means as clear cut

as that of the English, with the advance guard commanded by Constable

d'Albret and Marshal Boucicaut along with the Dukes of Orleans and Bourbon,

as well as the Counts of Eu and Richemont. The main body was under the

Dukes of Bar and Alengon and the Counts of Nevers, Vaudemont, Blaumont,

Salines Grand-pre and Roussy, the rearguard under the Counts of Dammartin

and Fauquembergue, while the forces on the flanks were led by the Count of

Vendome and Clignet de Brebant. This complexity of the command structure

led to French commentators blaming it for the defeat that followed, as

described by the anonymous monk of Saint-Denis:

In the absence of the king of France and the dukes of Guienne, Brittany and

Burgundy, the other princes had taken charge of the conduct of the war. There is

no doubt that they would have brought it to a happy conclusion if they had not

shown so much disdain for the small number of the enemy and if they had not

engaged in the battle so impetuously, despite the advice of knights who were

worth listening to because of their age and experience... When it came to putting

the army into battle formation (as is always the usage before coming to blows)

each of the leaders claimed for himself the honour of leading the vanguard. This

led to considerable debate and so that there could be some agreement, they came

to the rather unfortunate conclusion that they should all place themselves in the

front line.

With the armies arranged, both sides stayed in their positions - the French

between the villages of Agincourt and Tramecourt while the English line of

battle was situated just outside of their camp at Maisoncelle. When it came

to a stand off, however, the English had much more to lose and Henry

decided to advance his men towards the French line, moving from around

1,000m (3,280ft) away to within around 300m (1,000ft), as the

St Albans

Chronicle

written by Thomas Walsingham relates:

Because of the muddiness of the place, however, the French did not wish to

proceed too far into the field. They waited about to see what our men, whom

This view of the Agincourt

they held cheap, intended to do. Between each of the two armies the field lay,

battlefield is taken from

scarcely 1,000 paces in extent... Because the French were holding their position

the Agincourt-Tramecourt

without moving it was necessary for the English, if they wished to come to grips

road looking towards

with the enemy, to traverse the middle ground on foot, burdened with their arms.

the English camp at

Maisoncelle. It is over

Somewhat surprisingly, this advance appears to have been largely uncontested this ground that the

by the French, and the English were able to take up their second position English army advanced

unmolested, which put them within range of bowshot of the French line and to take up their second

also gave them thick woods to both protect the archers on the flanks and position and launch

narrow the frontage available for any French advance.

the missile attack that

Once they had taken up this new position, Sir Thomas Erpingham, steward would start the battle.

of the Royal household and one of the most experienced officers in Henry's (Author's collection)

army, gave the archers the order to fire

and the 5,000 men, positioned on

both flanks, complied. This appears to

have provoked the French cavalry into

launching a charge at the archers'

positions. However, a combination of

the heavy going over ploughed fields,

the incessant arrow fire and the fact

they couldn't get round the flanks of

the archers because of the woods

meant that the French cavalry were

driven back. The charge was also not

31

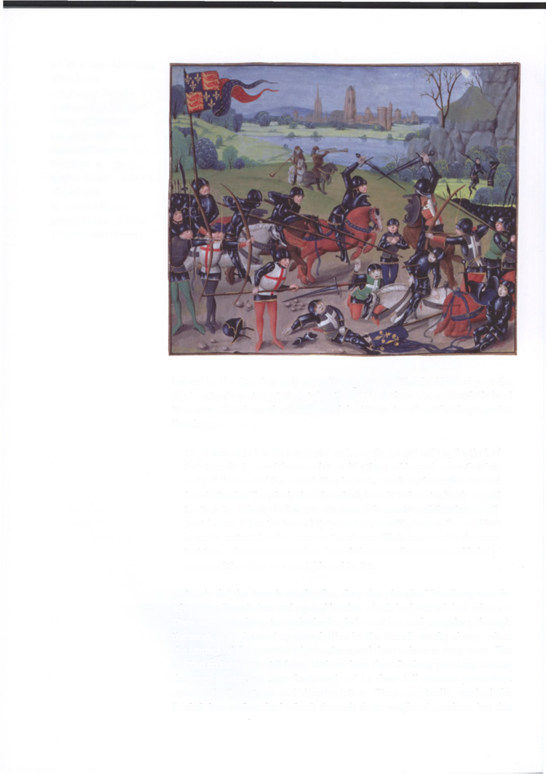

A 15th-century illustration

of the battle

of Agincourt from the

StAtbans Chronide

(Ms 6

f.243). This chronicle

was written by the mon k

Thomas Walsingham and

it contains an accurate,

if somewhat thin, account

of the battle.

(© Lambeth Palace

Library, London, UK/The

Bridgeman Art Library)

helped by the fact that only a small proportion of the 2,400 cavalry on the

flanks actually participated in it, less than 500, so there was no weight behind

the move. The chronicler Jean Juvenal des Ursins describes what happened to

the charge:

The French were heavily armed and sank into the ground right to the thick of

their legs, which caused them much travail for they could scarcely move their legs

and pull them out of the ground. They began to march until arrowfire occurred

from both sides. Then the lords on horseback, bravely and most valiantly wanted

to attack the archers who began to aim against the cavalry and their horses with

great fervour. When the horses felt themselves pierced by arrows, they could no

longer be controlled by their riders in the advance. The horses turned and it seems

that those who were mounted on them fled, or so is the opinion and belief of

some, and they were very much blamed for this.

Not only did the French cavalry flee, they also ploughed headlong into the

advancing French first and second battles, which had started their advance.

They were marching towards the English position and struggling through

the mud, now churned up even further by the French cavalry charge, when

the impact of the retreating horse disrupted their cohesion even more. The

English archers were still firing at them from their flanking positions, forcing

the men-at-arms to stay 'buttoned up' in their full armour protection,

causing further stress and disorientation. They eventually reached the

English line and pushed it back through sheer weight of numbers, but this

32

same numerical superiority was also causing the French lines to pile up on

each other and restricted their freedom of movement, while the archers still

tormented them from the flanks and, when they ran out of arrows,

intervened more directly on the battlefield, as the Burgundian chronicler

Enguerran Monstrelet relates:

Because of the strength of the arrow fire and their fear of it, most of the others

doubled back into the French vanguard, causing great disarray and breaking

the line in many places, making them fall back onto the ground which had

been newly sown. The horses had been so troubled by the arrow shot of the

English archers that they could not hold or control them. As a result the

vanguard fell into disorder and countless numbers of men-at-arms began to

A highly stylized

fall. Those on horseback were so afraid of death that they put themselves into