Henry V: The Background, Strategies, Tactics and Battlefield Experiences of the Greatest Commanders of History Paperback (10 page)

Authors: Marcus Cowper

Tags: #Military History - Medieval

The village of

Bethencourt-sur-Somme

lies on the banks of the

river Somme and it was

here, and at Voyennes,

that Henry V and his

army forced a crossing

of the river early on the

morning of 19 October,

thus enabling him to

steal a march on the

French advance guard,

who were forced to follow

the loop of the Somme

via Peronne. (Hektor)

their ranks by such columns of horse, all the archers were to drive in their

stakes... so that the cavalry, when their charge had brought them close and in

sight of the stakes would either withdraw in great fear or, reckless of their own

safety, run the risk of having both horses and riders impaled.

By this point the main French army was probably on the move from Rouen,

reaching Amiens once the English forces had passed further to the south.

Henry had to make a bold decision in order to get his men across the

Somme, and decided to cut off a great loop of the river, heading directly

towards the village of Ham. This would enable him to get ahead of the

French shadowing force, which would be forced to follow the long loop of

the Somme along the north bank. On the 18th they reached the village

of Nesle, and, on the 19th, crossing points were discovered between the

hamlets of Voyennes and Bethencourt-sur-Somme.

The French had damaged the approaches to these crossings, but they were

intact enough to allow the English to cross cautiously, which the vanguard did

on the morning of the 19th under the command of Sir Gilbert Umfraville and

Sir John Cornwall. Although the French attempted to interfere with the

crossing, by the time they had reacted too large a force of English troops had

already crossed and the main army was over the river by late afternoon,

marching on to Athies where they made camp.

Although across the river, they were by no means out of danger and on the

20th heralds came from the French camp offering battle. Henry replied that he

intended to march his army to Calais, and that the Princes of France could find

him in the open fields. From this point on the army marched as if they might

27

encounter battle at any moment,

with their armour on and coats of

arms displayed. Setting off on the

21st, the English passed Peronne

to the left and, shortly afterwards,

crossed over the tracks left by a

large host - this was certainly the

main French army which, having

arrived at Amiens, was now

moving on towards Bapaume.

From this point on the French

could cut the English army off at

any point they wanted, blocking

the main road to Calais with ease.

The English pressed on, spending

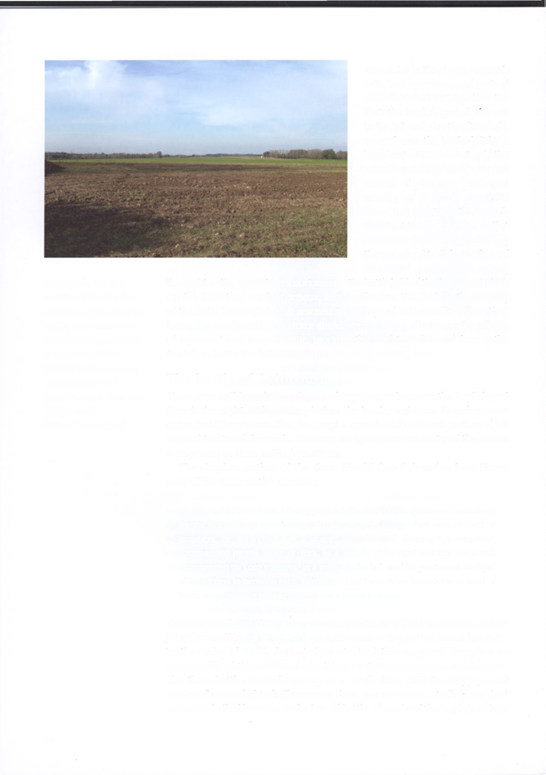

Maisoncelle was the

the night in the Mametz-Fricourt area on the battlefield of the Somme of 1916.

location of the English

On the 22nd they reached Acheux, and Doullens on the 23rd. By the evening

camp the night before the

of the 24th the English had reached the village of Maisoncelle, where they

battle, and it was from

found the combined French force ahead of them camped between the villages

here that they advanced

of Agincourt and Rousseauville, blocking the road to Calais and forcing the

to take up their first

English to battle the following day.

position on the morning

of 25 October 1415.

The battle of Agincourt

The view here is from the

There may well have been a degree of negotiation between the English and

village itself.

French the night and morning before the battle, and some French sources

(Author's collection)

claim that Henry was willing to accept a considerably reduced portion of his

original territorial demands. However, no agreement was met and the armies

were placed in their battle formations.

The chaplain author of the

Gesta Henrici Quinti

describes how Henry

arrayed his army in the morning:

And meanwhile our king, offering praises to God and hearing masses, made ready

for the field, which was at no great distance from his quarters, and, in want of

numbers, he drew up only a single line of battle, placing his vanguard,

commanded by the Duke of York, as a wing on the right and the rearguard,

commanded by Lord Camoys, as a wing on the left; and he positioned 'wedges'

of his archers in between each 'battle' and had them drive their stakes in front of

them, as previously arranged in case of a cavalry charge.

This was in effect a change in command, with Sir Gilbert Umfraville and Sir

John Cornwall being removed from command owing, as the chroniclers state,

to the Duke of York's fervent desire to lead the vanguard. His place as

commander of the rearguard was taken by the experienced Lord Camoys.

The three battles were drawn up in a single line, with the baggage and

non-combatants behind. This meant there was no reserve at all; Henry had

committed all of his men to the line of battle. The role of the English archers

28

in the battle has caused some

controversy over the years. The

chronicle written by the chaplain

quoted above states that they were

deployed as wedges between the

three divisions of men-at-arms.

However, some historians, notably

Jim Bradbury (

The Medieval Archer

Boydell & Brewer: Woodbridge,

1985), have claimed that this

would have been a most unusual

deployment for the era, and

would have weakened the line of

men-at-arms considerably. Instead

they suggest that the archers were

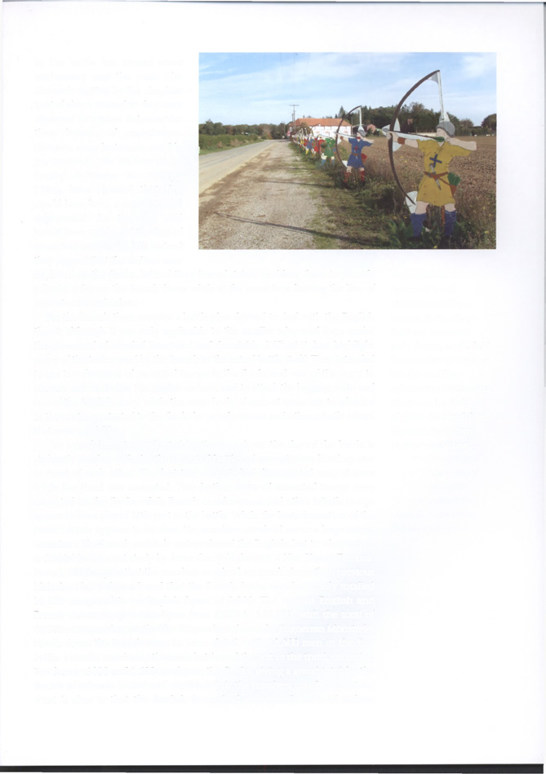

deployed on the flanks, behind their line of stakes, enabling them to provide The battlefield at

a flanking fire on the French forces while at the same time leaving the line of Agincourt is well

men-at-arms unbroken.

commemorated by a

For the French there survives a battle plan devised to deal with the English museum in the village threat; although it was only applicable to the smaller advanced force under itself and memorials

the command of Marshal Boucicaut and Constable d'Albret it does highlight and a Calvary on the field.

many of the tactics used by the French in the actual battle itself. They intended These models of archers to use two divisions of mounted troops to the flanks and rear of the army to line the road from

encircle and neutralize the English archers, and to attack the baggage train and Agincourt to Tramecourt, rear of the English army, while the main body of men-at-arms was to advance which runs just in front in the centre, protected to the flanks by crossbowmen and other missile troops of where the French front that were available.

line would have been.

The actual formation adopted by the French on the day of the battle is (Author's collection)

strikingly similar, with the three central battles of men-at-arms lined up one

in front of each other. The first two consisted of dismounted men-at-arms

while the third was mounted. Two further units of mounted troops were

mounted on the flanks, while French crossbowmen and other missile troops

appear to have played little part in the battle. While the basic formation of the

French forces appears to be clear, the numbers involved are to a large extent

uncertain. The French certainly outnumbered the English, but to what extent

is debatable. A recent study by Anne Curry (

Agincourt: A New History

Tempus:

Stroud, 2006) argues that the numbers involved are much closer than previous

historians have claimed, and that the French forces may have only totalled

12,000 compared to an English figure of 9,000. The various English and

French chronicles give any figure from 8,000 to 150,000, with the total of

60,000 occurring frequently. The Burgundian chronicler Enguerran Monstrelet

breaks down the French army in some detail, with 13,500 men in the first

battle, a similar number in the main battle and the rest in the third, excepting

two forces of 800 and 1,600 cavalry on the flanks, giving a grand total for the

French of between 35,000 and 40,000. While the numbers may be uncertain,

what is clear is that the English forces had a preponderance of archers

29