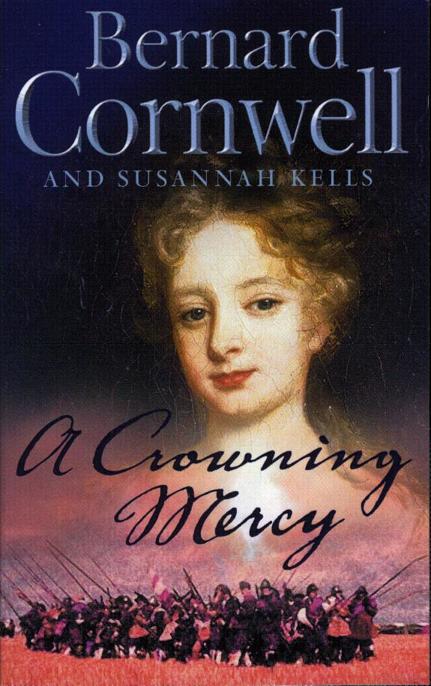

A Crowning Mercy

Authors: Bernard Cornwell

Tags: #Dorset (England), #Historical, #Great Britain, #Action & Adventure, #Fiction

| A Crowning Mercy | |

| Bernard Cornwell; Susannah Kells | |

| Harper Perennial (2003) | |

| Tags: | Fiction, Action & Adventure, Historical, Great Britain, Dorset (England) |

A highly entertaining, wonderfully colourful story, now revealed to be written by one of our favourite historical novelists.In mid seventeenth-century England, the nation was in upheaval. In the Dorset countryside, one sunlit afternoon, a young girl – illicitly bathing in a stream – first fell in love with a passing stranger. Her parents called her Dorcas, but he called her Campion and that's what she longed to be, then and forever.She had one gift left for her by her unknown father – a pendant made of gold, banded by tiny glowing stones and at its base was a seal engraved with an axe and the words: St Matthew. So when she flees before the unbearable, worthy suitor who is forced upon her after her forbidden meeting, she takes this and the delicate lace gloves with her, and hopes to find her father, and her lover.There are four of these intricately wrought seals – each owned by a stranger, each holding a secret within. And when all four seals are united, then the holder will have access to great wealth and power. That is Campion's inheritance.But to claim this and find again her summer love, she must follow the course her father's legacy charts for her. It is a road full of both peril and enchantment.A Crowning Mercy was first published in 1983 under the name Susannah Kells. It has been out of print for 10 years. HarperCollins are delighted to be able to re-publish it.

Synopsis:

One sunlit afternoon, a young girl -- illicitly bathing in a stream -- first fell in love with a passing stranger. Her parents call her Dorcas, but he called her Campion and that's what she longed to be, then and forever.

So when an unbearable suitor is forced on her, she flees to seek her lover, taking with her the one gift left to her by her unknown father -- a pendant of gold.

There are four of these jewels, each key to a secret, each owned by a stranger. When one person has them all, the holder will have access to great wealth and power. This is Campion's inheritance, one of peril and enchantment.

Bernard Cornwell was born in London, raised in Essex and now mostly lives in the USA. He is the author of the Sharpe series; the Arthurian series, the Warlord Chronicles; the Starbuck Chronicles, on the American Civil War;

Stonehenge;

and the Grail Quest series, the third of which,

Heretic,

has just been published in hardback. Susannah Kells is a pseudonym, now revealed to be Judy Cornwell.

A CROWNING MERCY

By

BERNARD CORNWELL and SUSANNAH KELLS

Version 1.0

Copyright (c) Bernard Cornwell 1983

ISBN 0 00 716823 3

Matthew, Mark, Luke and John,

The bed be blest that I lie on,

Four angels to my bed,

Four angels round my head,

One to watch, and one to pray,

And two to bear my soul away.

Thomas Ady

For Michael, Todd and Jill

PROLOGUE

1633

The boat slammed into a wave. Wind howled in the rigging and brought water stinging down the treacherous deck, driving the shuddering timbers into the next roller.

'Cap'n! You'll take the bloody masts out of her!'

The captain ignored his helmsman.

'You're mad, Cap'n!'

Of course he was mad! He was proud of it, laughing at it, loving it. His crew shook their heads; some crossed themselves, others, Protestants, just prayed. The captain had been a poet once, before all the troubles, and all poets were touched in the head.

He shortened sail an hour later, letting the ship go into irons so that it jerked and rolled on the waves as he walked to the stern rail. He stared through the rain and windspray, stared for a long while at a low, black land. His crew said nothing, though each man knew the sea room they would need to weather the low, dark headland. They watched their captain.

Finally he walked back to the helmsman. His face was quieter now, sadder. 'Weather her now.'

'Cap'n.'

They passed close enough to see the iron basket atop the pole that was the Lizard's beacon. The Lizard. For many this was their last sight of England, for too many it was their last sight of any land before their ships were crushed by the great Atlantic.

This was the captain's farewell. He watched the Lizard till it was hidden in the storm and still he watched as though it might suddenly reappear between the squalls. He was leaving.

He was leaving a child he had never seen.

He was leaving her a fortune she might never see.

He was leaving her, as all parents must leave their children, but this child he had abandoned before birth, and all that wealth he had left her did not assuage his shame. He had abandoned her, as he now abandoned all the lives that he had touched and stained. He was going to a place where he promised himself he could start again, where the sadness he was leaving could be forgotten. He took only one thing of his shame. Beneath his sea-clothes, hung about his neck, was a golden chain.

He had been the enemy of one king and the friend of another. He had been called the handsomest man in Europe and still, despite prison, despite wars, he was impressive.

He took one last, backward look and then England was gone. His daughter was left behind to life.

PART ONE

The Seal of St Matthew

1

She first met Toby Lazender on a day that seemed a foretaste of heaven. England slumbered under the summer heat. The air was heavy with the scent of wild basil and marjoram, and she sat where purple loosestrife grew at the stream's edge.

She thought she was alone. She looked about her like an animal searching for enemies, nervous because she was about to sin.

She was sure she was alone. She looked left where the path came from the house through the hedge of Top Meadow, but no one was there. She stared at the great ridge across the stream, but nothing moved among the trunks of heavy beeches or in the water meadows beneath them. The land was hers.

Three years before, when she had been seventeen and her mother dead one year, this sin had seemed monstrous beyond imagination. She had feared then that this might be the mysterious sin against the Holy Ghost, a sin so terrible that the Bible could not describe it except to say it could not be forgiven, yet still she had been driven to commit it. Now, three summers later, familiarity had taken away some of her fear, yet she still knew that she sinned.

She took off her bonnet and laid it carefully in the wide, wooden basket in which she would carry back the rushes from the pool. Her father, a wealthy man, insisted that she worked. St Paul, he said, had been a tentmaker and every Christian must have a trade. Since the age of eight she had worked in the dairy but then she had volunteered to fetch the rushes that were needed for floor-coverings and rushlights. There was a reason. Here, by the deep pool of the stream, she could be alone.

She unpinned her hair, placing the pins in the basket where they could not get lost. She looked about her again, but nothing moved in the landscape. She felt as solitary as if this was the sixth day of creation. Her hair, pale as the palest gold, fell about her face.

Above her, she knew, the Recording Angel was turning the massive pages of the Lamb's Book of Life. Her father had told her about the angel and his book when she was six years old, and it had seemed an odd name for a book. Now she knew that the Lamb was Jesus and the Book of Life was truly the Book of Death. She imagined it as vast, with great clasps of brass, thick leather ridges on its spine and pages huge enough to record every sin ever committed by every person on God's earth. The angel was looking for her name, running his finger down the ledger, poised with his quill dipped in the ink.

On the Day of Judgment, her father said, the Book of Life would be brought to God. Every person would go, one by one, to stand before His awful throne as the great voice read out the sins listed in the book. She feared that day. She feared standing on the floor of crystal beneath the emerald and jasper throne, but her fear could not stop her sinning, nor could all her prayers.

A tiny breath of wind stirred the hair about her face, touched silver on the ripples of the stream and then the air was still again. It was hot. The linen collar of her black dress was tight, its bodice sticky, the skirts heavy on her. The air seemed burdened by summer.

She put her hands beneath her skirts and unlaced her stocking tops just above her knees. The excitement was thick in her as she looked about, but she was sure she was alone. Her father was not expected back from the lawyer in Dorchester till early evening, her brother was in the village with the vicar, and none of the servants came to the stream. She pulled her heavy stockings down and placed them in her big leather shoes.

Goodwife Baggerlie, her father's housekeeper, had said she should not dally by the stream because the soldiers might come. They never had.

The war had started the year before in 1642 and it had filled her father with a rare, exalted excitement. He had helped to hang a Roman Catholic priest in the old Roman amphitheatre in Dorchester and this had been a sign from God to Matthew Slythe that the rule of the Saints was at hand. Matthew Slythe, like his household and the village, was a Puritan. He prayed nightly for the King's defeat and the victory of Parliament, yet the war was like some far-off thunderstorm that rumbled beyond the horizon. It had hardly touched Werlatton Hall or the village from which the Hall took its name.

She looked about her. A corncrake flew above the hayfield across the stream, above the poppies, meadowsweet and rue. The stream surged past the pool's opening where the rushes grew tallest. She took off her starched white apron and folded it carefully on top of the basket. Coming through the hedged bank of Top Meadow, she had picked some red campion flowers, and these she put safely at the basket's edge where her clothes could not crush the delicate five-petalled blossoms.

She moved close to the water and was utterly still. She listened to the stream, to the bees working the clover, but there was no other sound in the hot, heavy air. It was the perfect summer's day; a day devoted to the ripening of wheat, barley and rye; to the weighing down of orchard branches; a day of heat hazing the land with sweet smells. She was crouching at the very edge of the pool, where the grass fell away to the gravel beneath the still, lucid water. From here she could see only the rushes and the tops of the great beeches on the far ridge.

A fish jumped upstream and she froze, listening, but there was no other sound. Her instinct told her she was alone, but she listened for a few seconds more, her heart loud, and then with swift hands she tugged at her petticoat and the heavy, black dress, pulled them up over her head, and she was white and naked in the sun.

She moved swiftly, crouching low, and the water closed about her cold and clean. She gasped with the shock and the pleasure of it as she pushed herself into the deep place at the pool's centre, giving herself up to the water, letting it carry her, feeling the joy of fresh cleanness on every part of her. Her eyes were shut and the sun was hot and pink on them -- for a few seconds she was in heaven itself. Then she stood on the gravel, knees bent so that only her head was above the water, and opened her eyes to look for enemies. This pleasure of swimming in a summer stream was a pleasure she must steal, for she knew it to be a sin.

She had found she could swim, an awkward paddling stroke that could take her across the pool to where the stream's swift current tugged at her, turned her, and drove her back to the pool's safety. This was her sin, her pleasure, and her shame. The quill scratched in the great book of heaven.

Three years ago this had been something indescribably wicked, a childish dare against God. It was still that, but there was more. She could think of nothing, nothing at least that bore thinking about, that would enrage her father more than her nakedness. This was her gesture of anger against Matthew Slythe, yet she knew it to be futile for he would defeat her.

She was twenty, just three months from her twenty-first birthday, and she knew that her father's thoughts had at last turned to her future. She saw him watching her with a brooding mixture of anger and distaste. These days of slipping like a sleek, pale otter into the pool must come to an end. She had stayed unmarried far too long, three or four years too long, and now Matthew Slythe was finally thinking of her future. She feared her father. She tried to love him, but he made it hard.