Henry V: The Background, Strategies, Tactics and Battlefield Experiences of the Greatest Commanders of History Paperback (19 page)

Authors: Marcus Cowper

Tags: #Military History - Medieval

Bishop of Winchester and, from 1426, Cardinal.

The split in the council developed into a pro-war

party - led by Gloucester - and those who sought

a more conciliatory line - led by Beaufort.

In France matters were simpler, particularly

when Charles VI died only seven weeks after

Henry on 21 October 1422. This left John, Duke

of Bedford, as regent for Henry VI in France and he

carried out his duties with great ability, securing the

Anglo-Burgundian alliance through his marriage to

Anne of Burgundy in June 1423. He won battlefield

victories over Anglo-Scots forces at Cravant in 1423

and Verneuil in 1424 that opened the way for

further English conquests and advances into Maine

and down to the Loire, leading to the siege of

Orleans in October 1428. However, the French,

inspired by Joan of Arc, raised the siege of Orleans

in 1429 and defeated the English in battle at Patay

in the same year, opening up the road to Reims for

Joan and the Dauphin, with him being crowned

Charles VII there on 17 July 1429. This caused

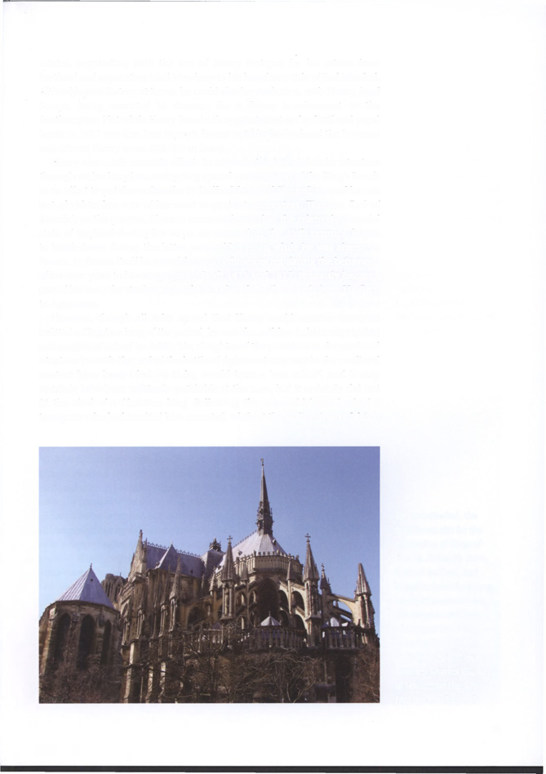

An illustration from a

a crisis in the English possessions in France with Paris itself threatened.

15th-century French

Although Bedford managed to stabilize the situation, momentum had swung

manuscript stored in the

back to the French and, following Bedford's death in 1435, the Duke

Bibliotheque Nationale,

of Burgundy split with the English and allied himself to Charles VII through

Paris (Ms. franqais 2678,

the Treaty of Arras, irrevocably shifting the balance of military power against

fol.35 v. Paris), showing

the English forces, with Paris falling in 1436. Henry VI's assumption of full

the signing of the Treaty

power did little to halt this trend, and by 1440 Harfleur had been reconquered

ofTroyeson 21 May 1420.

by the French before a truce was agreed in May 1444. This lasted for five years

Henry V is shown to the

until Charles VII, having built up his forces, declared war on 17 July 1449.

left with Philip of

In a rapid campaign he swept up the remaining English positions in

Burgundy to the right.

Normandy, with Rouen falling on 29 October and the English decisively

Philip's abandonment of

defeated at Formigny on 15 April 1450; Cherbourg, the last English-held place

his English alliance and

in Normandy, finally surrendered on 12 August. Charles VII then turned to

reconciliation with Charles

Gascony and cleared the English from their last major possession in France,

VII in 1435 proved the

with Bordeaux finally falling on 19 October 1453.

decisive blow for English

The series of defeats in Normandy and Gascony, combined with Henry

hopes in France.

VI's vacillating leadership, led to a series of increasingly bitter disputes

(akg-images/VISIOARS)

between his magnates, with Edward, Duke of York, leading the calls for

reform. These aristocratic disputes would break out into the Wars of the Roses

that would ultimately see the downfall of the Lancastrian kingdom of France

as well as England.

So Henry V's achievements did not prove to be particularly long lasting, but

his battlefield victory at Agincourt was stunning, and his campaign to reduce

the fortifications of Normandy and beyond was impressive in its planning,

organization and intensity, a fact recognized by French commentators as well

56

as more biased English ones. He benefited enormously in both campaigns

from a fatal lack of unity on the French side caused by the state of near civil

war that existed between the Armagnac and Burgundian factions and the

mental incapacity of Charles VI. So much of the solidity of Henry's conquests

was based upon his reputation and authority and, following his early death

and the reconciliation between Burgundy and the Crown, there was little that

the English could do to preserve their territories in France.

I N S I D E T H E M I N D

Henry V has been heralded by many as the perfect medieval king, lauded by

the historian K. B. MacFarlane as 'the greatest man that ever ruled England',

while contemporary commentators, both English and French, praised his

abilities and achievements. These fitted neatly into the medieval paradigm

of kingship, based around the ideal king being militarily brave and successful,

a defender of the faith and Christian orthodoxy and an impartial upholder

of law and order.

In many ways Henry certainly did fill these criteria. That he was personally

brave is undoubted - his severe wounding in the face at Shrewsbury is an early

example of this, with Henry returning to the battle and only seeking medical

aid once the victory was won. During the Agincourt campaign he exposed

himself to danger at the siege of Harfleur and then fought in the front line of

men-at-arms at the battle of Agincourt itself. Various chronicles have him

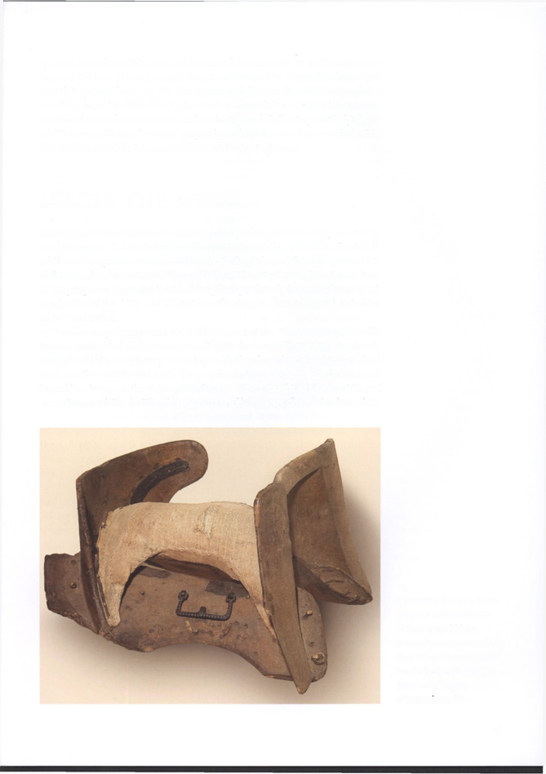

The saddle of Henry V from

his tomb in Westminster

Abbey. It would have

originally been covered in

blue velvet decorated with

fleurs-de-lys. (Copyright

Dean and Chapter

of Westminster)

57

standing over the body of his brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, fighting

off the French, while other sources relate how 18 squires of the Sire de Croy

attempted to kill him, with one managing to strike one of the fleurets off his

crown before they were all killed (other sources attribute this to the Duke of

Alen^on). The chronicler of St Albans, Thomas Walsingham, says of Henry at

the battle: 'He both inflicted and received cruel wounds, offering an example in

his own person to his men by his bravery in scattering the opposing battle lines

with a battle axe', while Tito Livio says he fought Tike an unvanquished lion'

and the

Gesta Henrici Quinti

relates how 'Nor do our older men remember any

prince having commanded his people on the march with more effort, bravery

or consideration, or having, with his own hand, performed greater feats of

strength in the field.' This impression of personal bravery is confirmed in the

later campaigns when he exposed himself to danger at various sieges, including

fighting in the mines beneath the town of Melun during the siege of 1420.

However, his military achievements, particularly in the campaigns from 1417

to 1420, were not based so much upon his personal reputation for bravery, but

upon his organizational and logistic skills in keeping a well-supplied army in the

field year round, enabling him to take town after town, fortress after fortress,

constantly keeping his enemies under pressure and creating a momentum

behind his conquests that led to some towns and fortifications capitulating

merely at the arrival of his army. His success in these various campaigns and

sieges merely confirmed in his eyes, and many of his contemporaries, that he

and his cause were favoured by God.

His personal religious beliefs appear to have been orthodox and deeply

held. Even before his accession to the throne he was involved in the

suppression of the Lollard heresy, being present at the burning of John

Badby in 1409 and supporting Archbishop Thomas Arundel's purge of

Lollards from Oxford University in 1411. After his accession he himself

had to deal with the Lollard-inspired Oldcastle Revolt in 1414, though it

is possible that contemporary chroniclers have over-emphasized the

seriousness of this rebellion.

Despite the dissolute reputation of the 'Hal' of Shakespeare's

Henry IV, Part

I

and

Henry IV, Part II,

there is little evidence of any disorder in his personal

life prior to his gaining the throne, and his personal religious fervour is

further attested to by his interest in and patronage of the austere Carthusian

Order. He was the last English king to found new religious houses, and the

Carthusian house at Sheen and Brigittine house at Syon, both founded in

1415, were the last major foundations prior to the Reformation.

His interest in law and order and impartial justice, key aspects of medieval

kingship, also appear to have been sincerely held and to have applied both in

England and France. Right at the beginning of his reign he offered a general

pardon for offences committed in his father's reign, a policy that was

particularly effective in Wales following the collapse of the Glendower revolt.

He was also particularly conciliatory to the descendants of those who had

fallen foul of his father during the turbulent years of the early 15th century,

restoring men such as John Holland - the future Earl of Huntingdon - to his