Grow a Sustainable Diet: Planning and Growing to Feed Ourselves and the Earth (12 page)

Read Grow a Sustainable Diet: Planning and Growing to Feed Ourselves and the Earth Online

Authors: Cindy Conner

Tags: #Gardening, #Organic, #Techniques, #Technology & Engineering, #Agriculture, #Sustainable Agriculture

The first year I became a market gardener my main crop was lettuce. I had grown lettuce for my family before, but that year it was in a third of my garden. Talk about upsetting the balance! Things were going along fine until a week before my first harvest when the slugs moved in. I discovered that the slugs came out on the leaves just before dusk and were still there in the early morning while the dew was on the plants. I would go out with a spoon and cup to scrape them off. It was only a problem until the hot days of summer set in. I had to be diligent the first year. The second year I was watchful and kept after the slugs for the few weeks they were a problem, but they never were as bad as the first year. After that I don’t remember ever having a problem. We would see slugs when we washed the lettuce for market, but they didn’t do enough damage to think about. Since we had a healthy ecosystem in the garden, I imagine that the birds and toads worked slug harvest into their routine and took care of them for us.

I mentioned that when you mix different crops in the same bed it is called interplanting. In permaculture, planting certain things together like that is referred to as a guild. Sometimes I have interplanted things for convenience, such as lettuce and cabbage. I set the cabbage out at their regular spacing — about 15″ — and the lettuce transplants go in between the cabbage plants. They all grow together in the bed until the leaves begin to touch. That’s when I harvest the lettuce. With lettuce in the bed there is no space for weeds. If you find things that work well together, think of them as a guild that is always planted together. The Three

Sisters — corn, beans, and squash — is an example of interplanting. Sally Jean Cunningham wrote

Great Garden Companions

, a good resource for information on companion planting. She mixes herbs, flowers, and vegetables in her beds. That book has been an inspiration to Brent, one of my friends you meet in my garden planning DVD. He has moved since we filmed for the video, but only to another part of Richmond, Virginia. His front and back yards are filled with gardens and he even has chickens now. Some of his beds look like they could come right out of Cunningham’s book. Once when I was there I saw white cabbage butterflies flitting about his yard, but no holes in the leaves of his brassica plants. I also saw wasps flying along those greens looking under the leaves for a snack. I’m sure they were looking for larvae or eggs. Everything was as it should be. Although I don’t remember all that he had planted with those cabbage family plants, I do remember that hairy vetch was blooming in there.

Developing borders is a great opportunity to put plants together in the garden, while establishing permanent plantings and habitat. Even annuals will do to start. Here’s where you can put the herbs and flowers that add so much to life. You can plant bulbs in your borders as well. This is all part of establishing the ecosystem. Think of it as a mini-hedge. In fact, it is good to learn about hedges. They are useful wherever you have room for them. One side of my large garden has always had a fence, so the honeysuckle, day lilies, and other things that just grow there are permanent plantings. It’s sort of wild. The other three sides are planted on the inside of the fence, but most years grass grows up to the fence on the outside. Big on my to-do list is to establish a perennial border on the outside of the fence on those three sides. On the inside, I have established hazelnuts (filberts) on the north side of the garden and blueberries on the west side. Annual vegetables are on the south side.

One summer I had some great looking marigolds growing on the outside of the garden fence. Marigolds are always good to have in and around your garden. Our son Luke had a team of calves that he was

training as oxen and they had reached the limits of our pasture. For some extra grazing, he put up electric fence to use the grassy area surrounding the garden. We assumed the 4′ garden fence would suffice to keep them from the garden. I thought I would have to sacrifice the marigolds, but the steers didn’t even nibble on them. Since they stayed away from the marigolds, they stayed away from the fence. The following spring, they were let into that area again, but there were no marigolds along the fence. The steers came up to the fence and dropped their heads over, leaning on the fence and eating the collards that I had going to seed. Granted, the animals were bigger now, but that made me think that if I had highly scented perennials there, maybe those plants would keep back the steers and possibly other animals. The marigolds were great for that, but they are seasonal. There are books about plants that wildlife don’t like. Maybe a combination of those plants, along with a fence, would mean the fence doesn’t have to be so high. Luke’s oxen have moved on to other pastures, but now that we’ve considered that area outside the garden as potential extra grazing, I want to establish a border that won’t get eaten. It will be an interesting challenge.

Comfrey is good to have in your garden. A border of comfrey planted eighteen inches apart has kept wire grass from encroaching in one of my gardens. Comfrey dies back in the winter, but pops up in early spring to form a nice green fence. You could harvest comfrey for compost material or to feed small livestock. In that case, their manure goes to the compost. Comfrey won’t do, however, in the border that I don’t want grazed by the steers. They ate it down so thoroughly along one fence that it never came back.

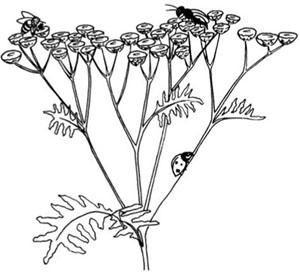

I discovered tansy in my early years here at the farm when I was searching for a solution to the beetle problem with my potatoes. I had read that tansy was a good companion plant for potatoes, so I planted tansy seeds in my potato bed. The tansy grew well, but of course the new plants didn’t do much for the potatoes that year. Since tansy is a perennial, it wouldn’t be good to leave it in the garden bed, so I transplanted it along our porch. It has done great there. It is still close enough to the garden so the beneficial insects it attracts are nearby and, since it tends to spread out, I can dig some at any time to plant another place or give to

friends, redistributing the surplus. Cunningham refers to tansy as “probably the single best attractor for beneficial insects.” The list of insects she’s found on her tansy includes the spined soldier bug, the same one the ATTRA Farmscaping publication said would go after the Colorado potato beetle.

How the paths are handled is a consideration as part of your companion planting/farmscaping plan. Tilling destroys any habitat that might be there for the beneficial insects. In

Chapter 2

I mentioned that I have white clover or leaf mulch in my narrow paths and grass in my wide paths. This provides a nice habitat for beneficials. According to the ATTRA Farmscaping publication, ground beetles like to live in permanent plantings, white clover, and mulch. They may help with the Colorado potato beetle problem, in addition to problems with slugs, snails, cutworms, and cabbage-root maggots. Just imagine if chemicals are sprayed in the paths. Besides the vegetation, all the beneficial life in the paths would perish.

Don’t be too quick to clean up the edges of your property. Eradicating every weed and trimming every blade of grass is considered desirable to some, but at what cost? Weedy fencerows, as well as other shady, moist spots can be homes to spiders. Spiders eat only insects, and live ones at that. All those insects get thirsty, so make sure to provide some water for them. It can be in shallow dishes you set out, a pond in your garden, or even a small wetland. I have only touched the surface of all you could do with companion planting, but I hope I’ve given you an understanding of what is necessary to allow all the benefits of an ecosystem to develop. Diversity is what we are after in a sustainable garden. The more different things we have, the better.

Plan for Food When You Want It

Y

A

G

OTTA

H

AVE A

P

LAN

! That was the working title of our garden plan DVD. The final title is

Develop a Sustainable Vegetable Garden Plan

, which is more descriptive, but I like the working title better. “Ya gotta have a plan” was what I found myself saying to people who would come to me with questions. It would be nice if all you had to do was walk out to your garden and spirit would guide you on what and when to plant, and when and how long your harvest would be — and that might very well work for you. I partner with spirit a lot and know that spirit can’t do it alone. Being in a partnership means we have to do our part, which means do our homework by learning all we can about what we want to eat and what we will be planting. For those of you who discount spirit in your lives, all the more reason to do your homework, since it’s all on you. Have you ever heard that you need to develop clear intentions of what you want to accomplish? A plan is where you lay out your intentions for the garden for the year. Things don’t always go as planned, but that is part of the experience. Everything becomes a learning experience, whether it worked out as you expected or not. Stay flexible and don’t ever stop learning.

There are a lot of steps to planning and growing a sustainable diet. Sometimes you’ll be working on many steps at the same time. No doubt,

by this time you have a list of things you want to grow and are wondering how you will fit it all in your garden. If you’ve made your garden map, you know how much space you have to work with. Fitting everything in has a lot to do with timing.

Unless you’ve been growing for a while, you might not know how long it takes from seed to transplanting in the garden, how long that crop will be in the garden until the beginning of harvest, and how long the harvest might be. Even if you are an experienced grower, it is good to think it out anew once in a while. Having that information in one place is really helpful, which is why I’ve come up with worksheets. In this chapter you will find the Plant/Harvest Times (

Figure 7.1

) and the Plant/Harvest Schedule (

Figure 7.2

) worksheets. One of the great things about teaching all those years at the community college is that every year I went over all the material again, refining it each time. When I grew for my family, and then for the markets, I worked with this crop information without the benefit of worksheets. Having it all in one place facilitates planning and is helpful mid-season when times are busy. You don’t have to stop and think just which catalog you found that seed in to check the days to maturity, or whatever it is you have a question about.

Taking a look at the Plant/Harvest Times worksheet, you will see a place for the dates of the last spring frost and the first fall frost. Of course, you don’t actually know when those dates are until they pass, but you can put the expected dates for your area there. If you don’t know when that is, you could call your county Cooperative Extension Service, ask your gardening neighbors, or find the dates online at

plantmaps.com

. For starters, put the expected dates there, but later on you could go back and add the actual dates. You will have a record specific to your garden. A word of caution — just when you think you know what to expect, things change. (I know I already gave you an example of that in

Chapter 3

with the rainy October, but here is another one.) Our usual last spring frost date is about April 25 here. We live out in the country.

In the city of Richmond, Virginia, just fifteen miles away, it might be a little earlier because of all the concrete soaking up the sun. I would put out my tomato transplants on April 25 and mulch them with leaves so that I wouldn’t have to weed at all. One year the weather was warming up nicely and I put out the tomatoes, as usual. I got busy with family and life in general over the next week and obviously was not paying attention to the weather forecast because we had a killing frost on May 1 and I lost many tomato plants. I realized later that they might have survived if I had not mulched them. The soil was warmer than the air and if the mulch wasn’t there, the soil would have probably warmed those little transplants enough to keep them alive. With the mulch down, the transplants were insulated from the heat of the soil and left to the mercy of whatever temperature the air was.