Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (29 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

By far the worst violence came that same month in the rural Malabar district on the Indian Ocean coast, where a community of Muslims known as Mappilas, also Moplahs, rose in rebellion, crying

jihad and brandishing the Khilafat flag, after a couple of skirmishes with the police in which two British constables had been killed. Tiny Khilafat kingdoms were then proclaimed by the insurgents, and in some of these, Hindu homes and temples were set ablaze, women raped, and children slaughtered. The doctrine of

nonviolence had never reached the Malabar district; political meetings had, in fact, been banned there.

That was hardly an excuse for the gruesomeness or scale of the carnage: six hundred Hindus reported killed, twenty-five hundred forcibly converted to Islam. Gandhi and Muhammad Ali were denounced as infidels when they called on the insurgent leaders to disavow violence. The Raj dealt severely with the rising, blaming the noncooperation movement and hanging some two hundred rebels.

The next month Muhammad Ali was arrested on conspiracy charges at a train station in the Telugu-language region of southeastern India (today’s Andhra Pradesh), including the charge of “conspiracy to commit mischief,” while traveling with the Mahatma from Calcutta to

Madras. The British, who’d been looking for an occasion to re-exert their authority, found it in a series of statements by the maulana arguing that

Islamic law forbade Muslims to enlist or serve in their army. Gandhi’s reaction says a lot about the fecundity of his imagination, the range of his aspirations, and his adaptability as a political tactician. A week after seeing Ali hustled from the station by a police detachment, he appeared in the South Indian town of Madurai bare chested in a loincloth: in the attire, that is, that would be his unvarying guise for the rest of his life. It’s the way he’d been dressing at the ashram on the Sabarmati River, outside Ahmedabad, for several years; in public, he’d continued to wear a kurta, dhoti, and cap. This was the first public outing of his new, very basic costume.

Being Gandhi, he hastened to explain the symbolic meaning of the change. His disrobing could be read in several ways: as a tribute to the imprisoned maulana and the other Khilafat leaders rounded up with him; or as a subtle shift of emphasis, a recognition that the Khilafat movement would soon be played out, at least as far as Hindus were concerned, that the larger national movement needed a new mobilizing tool. Gandhi had already seized on the spinning wheel for that purpose. For the goal of swadeshi to be achieved, he reasoned, there had to be enough hand spinning and hand

weaving across India to replace the manufactured imported cloth being burned and boycotted as his campaign for swadeshi caught on. Without swadeshi and all it entailed, he now argued, there could be no swaraj. And only with swaraj

—

giving India the ability to engage diplomatically with the world—could there be any settlement of the Khilafat problem. Once the highest priority of the noncooperation movement, the preservation of the Khilafat was now to be seen as a potential by-product of its success.

Gandhi was pointing the way to “full swadeshi” by showing the millions who were too poor to cover their whole bodies with newly woven homespun that it really wasn’t necessary. “Let there be no prudery about dress,” he now said. “India has never insisted on full covering of the body for males as a test of culture.”

Later, he would explain the symbolism he invested in the loincloth by saying, “

I wish to be in touch with the life of the poorest of the poor among Indians … It is our duty to dress them first and then dress ourselves, to feed them first and then feed ourselves.”

If they could follow the winding path of his logic, Indian Muslims might see his wearing of the loincloth as proof of his continued devotion to the Khilafat cause. Otherwise there was a good chance they’d perceive

Gandhi to be drifting away from them. Muhammad Ali might have pointed out, were he not by this time in detention in Karachi, that the culture that Gandhi was describing so avidly was distinctly Hindu. “

It is against our scriptures to keep the knees bare in this fashion,”

Maulana Abdul Bari, a leading religious authority who’d been prominent in the Khilafat agitation, subsequently informed the Mahatma.

Gandhi was starting a new variation on the fugue he was forever composing out of his various themes. Recalling perhaps how few South African Muslims were at his side when he marched across the Transvaal border in the 1913 satyagraha, he’d understood from the start of the noncooperation campaign that he could only speak to Muslims through other Muslims: Muhammad Ali, for instance. “

I can wield no influence over the Mussulmans except through a Mussulman,” he said. He’d also understood the improbability of the Khilafat as an Indian national cause.

For him, it was less a cause than an investment: “the opportunity of a lifetime” for Hindus to demonstrate their stalwartness, their trustworthiness, to Muslims who, he kept suggesting, if not quite promising, would be likely to respond in kind by respecting the tender feelings of Hindus for the sacred cow. Ergo, according to this logic, preserving the Khilafat was the surest way to preserve the cow. Nothing like this opportunity would “recur for another hundred years.”

It was a cause for which he was “ready today to sacrifice my sons, my wife and my friends.” In the short run, it was also a way to bind Muslims into the national movement that, thanks in no small measure to their support, he now led. The odds against it working were overwhelming, but who can now say, considering all that has happened since in confrontations between Hindus and Muslims, that Gandhi had his priorities wrong?

Gradually, he disengaged from the Khilafat agitation, which meant disengaging from Muslim politics, but Hindu-Muslim unity remained one of his main themes through to what might be called his tragic last act as Hindus and Muslims slaughtered each other at the time of

partition. In September 1924, Gandhi fasted for the first but not last time against Hindu-Muslim violence following riots in Kohat, a frontier town south of Peshawar in what’s now Pakistan. He said he was fasting for twenty-one days as a personal “penance.” The flash point for this killing spree, which resulted in an official death count of thirty-six and the flight of Kohat’s entire Hindu community, was a grossly blasphemous life of the Prophet written by a Hindu.

While it had nothing to do with Gandhi, he held himself responsible in the sense that he’d been “instrumental in bringing into being the vast energy of the people” that

had now turned “self-destructive.” To demonstrate that the fast was not against Muslims or on behalf of Hindus, the main sufferers on this occasion, he made a point of camping in Muhammad Ali’s Delhi bungalow during his starvation ritual. “

I am striving to become the best cement between the two communities,” he wrote. Twenty-four years later he’d fast again in Delhi with the same purpose. On each occasion, Hindu and Muslim leaders, fearful of losing that “cement,” gathered at his bedside and vowed to work for peace. A shaky armistice would follow and hold until an obscure agitator, somewhere on the subcontinent, threw off the next spark.

Gandhi the politician retained a cool realist’s grip on his own limitations in this highly charged sphere after the

waning of the Khilafat cause. Never was it more clearly and coldly displayed than in 1926, when his second son, Manilal, now resettled in South Africa, realized he was in love with a young Muslim woman in Cape Town whose family had played host to his father in years gone by. Her name was

Fatima Gool, and she was known as Timmie. When word of the interfaith love match reached Gandhi at his ashram in Gujarat, he wrote to his son telling him he was free to do as he wanted. Then, as his great-granddaughter Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie observes in her finely wrought biography of Manilal, “

the rest of the letter in fact closed the doors on free choice.”

Generally speaking, Gandhi deplored marriage as a failure of self-restraint (ever since he unilaterally declared himself a

brahmachari

) and religious conversion as a failure of discipline (since he briefly contemplated it for himself in his Pretoria days). So he was hardly likely to celebrate intermarriage as a realization of Hindu-Muslim unity. His letter reads like a dry lawyer’s brief, or a political consultant’s memo, devoid of any expression of feeling for his son or the Gool family. Of its several arguments, the most forceful and hardest to refute is the politician’s: “Your marriage will have a powerful impact on the Hindu-Muslim question … You cannot forget nor will society forget that you are my son.” Persevering idealist though he was, he was seldom softhearted, least of all when it came to his sons.

Did the revivalist ever really believe that swaraj could come in a year, or that the caliphate could be preserved? The question is little different from asking whether modern political candidates believe the dreamy promises they make at the height of a campaign. For Gandhi, who was introducing modern politics to India, the question is especially fraught

because he was seen by his own people in his own time and place as a religious figure, more saintly than prophetic, more inspiring than infallible. He could thus be expected to lay down unmeetable conditions to achieve unreachable goals. At a certain level of abstraction from what we’re accustomed to calling reality, what he offered in 1920 and 1921 as a vision was obvious and inarguable, even and especially when it defied normal expectations. After all, if 100 million spinning wheels had produced enough yarn in a few months to clothe 300 million Indians, if state schools and courts had all emptied and colonial officials at every level found they had no one to ring for—if Hindu and Muslim India was that united and disciplined—then independence

would

have been within reach. Gandhi was telling his people that their fate was in their own hands; that much he surely believed. It was when these things failed to happen as he said they could that disillusion set in and the movement veered off course and slowed.

Shortly after the Mahatma donned his “symbolic disguise,” as

Robert Payne, one of his legion of biographers, termed his loincloth, he was challenged on the level of reality by

Rabindranath Tagore, the great Bengali poet, a Nobel laureate by the time he met Gandhi in 1915, and, later, the admirer who first conferred on him the title Mahatma. Tagore now wrote that Gandhi had “won the heart of India with his love” but asked how he could justify the bonfires of foreign cloth promoted by his followers in a country where millions were half-clothed. The gist of Tagore’s high-minded argument was that Indians needed to think for themselves and beware of blindly accepting such simplistic would-be solutions as the spinning wheel, even from a Mahatma they rightly revered. “

Consider the burning of cloth, heaped before the very eyes of our motherland shivering and ashamed in her nakedness,” he wrote. Gandhi swiftly replied with what may have been his most stirring prose in English, offering his retort on a less elevated level of reality, that of village India:

To a people famishing and idle, the only acceptable form in which God can dare to appear is work and the promise of food as wages. God created man to work for his food, and said that those who ate without work were thieves. Eighty per cent of India are compulsory thieves half the year. Is it any wonder if India has become one vast prison? Hunger is the argument that is driving India to the spinning wheel … The hungry millions ask for one poem—invigorating food. They cannot be given it. They can only earn it. And they can earn it only by the sweat of their brow.

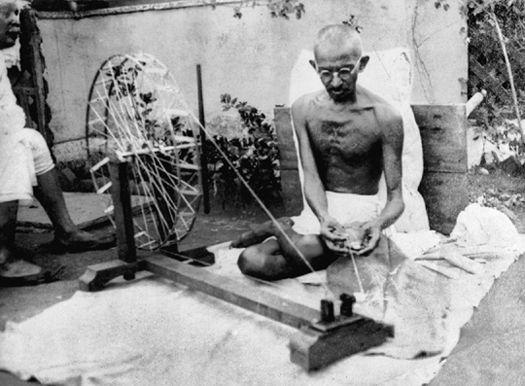

Gandhi at his charkha, 1925

(photo credit i6.2)

As far as the polemical exchange went, Gandhi may have bested Tagore, but soon he had to confront his own doubts. He was under pressure from impatient followers, Khilafat activists in particular, to launch an intensified campaign of mass

civil disobedience that would fill colonial jails. Gandhi tried to defer the campaign or at least limit its scope. Unsure that he had enough disciplined workers under his command, he worried about seeing his nonviolent campaign spill over into mass rioting, as it had in 1919, once demonstrators finally confronted the police. The month after the exchange with Tagore, rioting in Bombay caused him to suspend civil disobedience. Less than three months later, it happened again.

The authorities had banned public meetings. This spelled opportunity for satyagraha; across India, Congress leaders and followers by the thousands defied the ban, got themselves arrested, and went to jail. As the prisons filled, Gandhi fired off congratulatory telegrams to the most prominent inmates, hailing them as one might hail a class of new graduates. Their jailing, his telegrams asserted, was wonderful news. Then a lethal clash at an obscure place in North India called Chauri Chaura

moved Gandhi to order another suspension of his campaign—the third in less than three years—against the advice of close associates.

What happened in Chauri Chaura on February 5, 1922, fulfilled his worst fears. An angry crowd of roughly two thousand surrounded a small rural police station after having been fired on by a police detachment, which had then withdrawn and taken cover inside the building. The frustrated crowd, now a mob, soon set it ablaze. Driven out, policemen were hacked to death or thrown back into the flames; in all, twenty-two of them had been slaughtered with their assailants, so it was later said, shouting noncooperation catch-cries, including “

Mahatma Gandhi ki jai

”—“Glory to Mahatma Gandhi.”