Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (28 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

No one outside India seriously cared about the feelings of Indian Muslims on this issue or granted them any standing to be heard on it. This was true not only of the victorious Allies now dictating the peace

but also of the

Arab world, which was hardly sorry to be relieved of Turkish rule; it was even true of most Turks, who’d wearied of the sultan and his decadent court. To most Hindus as well, the future of the Khilafat would have been a matter of profound indifference had they not been exposed to Gandhi’s tireless and ingenious rationalizations for making its preservation a primary goal of India’s national movement. Even then, few understood what it was all about. Gandhi’s knowledge of Islamic history derived from his reading in South Africa of

Washington Irving’s

Life of Mahomet

and an English translation of the

Koran. He didn’t try to make the case for the Khilafat. He offered a simple syllogism, telling Hindus it was of supreme importance to their Muslim brethren and, therefore, to national unity, and, therefore, to them. Using an Indian measure that stands for ten million, he asked, “

How can twenty-two crore Hindus have peace and happiness if eight crore of their Muslim brethren are torn in anguish?”

Incomparably quixotic as it may appear today, the Indian struggle to preserve the authority of the Ottoman sultan became the preeminent Indian cause among Muslims. It’s easy to say that it was doomed from the start, but that wasn’t evident to them then. The coup de grâce wouldn’t come until 1924, when Mustafa Kemal, known as Atatürk, formally dissolved the caliphate, driving the last sultan into exile. Still the Khilafat movement lingered on in India, channeling the passion and resentments it had aroused into new reformist groupings, some of which had an influence beyond India that played back into the Arab world in significant ways.

One of these was a movement called the Tablighi Jamaat, or Society for the Propagation of the Muslim Faith, usually known as Tabligh, which from its start in India became “the most important element of re-Islamization worldwide,” according to the French expert

Gilles Kepel, “a striking example,” he says, of “a fluid, transnational, informal Islamic movement.” That may sound a little familiar:

a complex religious and ideological lineage could be traced over nearly a century from Muhammad Ali and other Indian proponents of the cause to present-day Islamists, including

Osama bin Laden, who made restoration of the caliphate one of

Al Qaeda’s war aims when he proclaimed his struggle against the United States.

Given that he deplored

terrorism and was no Muslim, it would be simply wrong, not to say grotesque, to set Gandhi up as any kind of precursor to bin Laden. But the remote cause of the Khilafat was equally important in his rise. It was on his mind in 1918 when he wrote to the viceroy, on his mind a year later when he spoke in a Bombay mosque on

the occasion of a national strike he’d called. The day of prayer and fasting was offered in April 1919 as a protest mainly against new legislation giving the colonial regime—in another haunting analogy to our own times—a slew of arbitrary powers it said it needed to combat terrorism. That supposedly nonviolent campaign quickly flared into riots in Bombay and Ahmedabad and

“firings,” confrontations in which the constabulary or military trained their weapons on surging unarmed crowds in the name of order. The first firing was in Delhi, where five were killed; another came two weeks later in the Sikh stronghold of Amritsar. There, on April 13, 1919, in the most notorious massacre of the Indian national struggle, 379 Indians taking part in an unauthorized but peaceful gathering were gunned down by Gurkha and Baluchi troops under British command in an enclosed square called Jallianwala Bagh for defying a ban on protests. By then, Gandhi was on the verge of calling off the national strike; he’d made a “Himalayan miscalculation,” he said, in allowing himself to believe the masses were ready for

satyagraha. To Swami Shraddhanand, an important Hindu spiritual leader in Delhi who questioned his bumpy, seemingly impulsive start-and-stop tactics, the Mahatma dismissively replied: “

Bhai sahib! You will acknowledge that I’m an expert in the satyagraha business. I know what I’m about.”

It took only six months for Gandhi to start paving the way to a resumed campaign. He had come up with a new tactic, which he named “non-cooperation.” He outlined it first to Muslims involved in the gathering Khilafat campaign, then in Delhi to a joint conference of Hindus and Muslims, also on the Khilafat. The concept, which can be found in embryo in

Hind Swaraj

, was initially sketchy, but Gandhi soon filled it in. Noncooperation came to mean withdrawing participation, in stages, from colonial institutions, rendering them hollow and useless. Lawyers and judges would be asked to boycott the courts; would-be legislators would not take part in existing councils and provincial assemblies the British were promising; students would gradually abandon state schools, attending instead new ones to be improvised along Gandhian lines, with instruction, of course, in Indian languages instead of English; officials would surrender the status and security of their jobs; and, ultimately, Indians would learn to turn their backs on service in the armed forces, especially in Mesopotamia—soon to be known as Iraq—which the British had snatched from the sultan; those who’d received medals from the Raj would be called on to return them; honorary titles would be renounced. It was an exhilarating vision. One by one the props under British rule would be removed. The vision changed the lives of hundreds,

maybe thousands, of Indians who joined the movement on a full-time basis. It inspired millions more.

Muslims didn’t become unconditional converts to satyagraha as a doctrine. The

Koran, after all, sanctions

jihad in a just cause and doesn’t rule out violence. But for the better part of two years, the Hindu Mahatma won acceptance as their campaign’s chief tactician, the author of noncooperation. And with their support, he stepped to the fore for the first time in the national movement, on a unity platform embracing all his causes, among which the literally outlandish cause of preserving the caliphate in Constantinople for the Muslims of India regularly now emerged as first among equals. Gandhi had formed an ad hoc committee called the Satyagraha Sabha for his earlier agitation against the antiterrorism laws. Now, in December 1919,

the month after the first Khilafat conference, he made what he later called “my real entry into Congress politics” at the movement’s annual session in Amritsar.

There he was joined by the Ali brothers, Muhammad and Shaukat, just released from confinement. The Alis created a greater stir in Amritsar even than Gandhi. They were greeted, one scholar records, with “

cheers, tears, embraces, and a veritable mountain of garlands.” A rising tide of Hindu-Muslim unity was now in the offing, hard to imagine in an era in which predominantly Hindu India and predominantly Muslim Pakistan confront each other as nuclear powers. By design, three conferences were taking place simultaneously: in addition to the Indian National Congress, the

Muslim League and the

Khilafat Committee were meeting.

In June the Central Khilafat Committee named an eight-man panel, including the Ali brothers, “to give practical effect” to a program of noncooperation. Gandhi, the only Hindu among the eight, was listed first.

The following September, Muslim votes ensured the adoption of Gandhi’s noncooperation program by a narrow margin at a special Congress session in Calcutta, with the preservation of the caliphate now underscored as a primary goal of the national movement. “

It is the duty of every non-Moslem Indian in every legitimate manner to assist his Mussulman brother, in his attempt to remove the religious calamity that has overtaken him,” declared the resolution, written by Gandhi. Without Muslim votes, Gandhi’s first challenge to the Congress to adopt satyagraha would almost certainly have foundered. The Mahatma hadn’t won over the political elite; with the backing of the Alis, he’d swamped it. It was at Calcutta that he first held up the prospect of “swaraj within a year.”

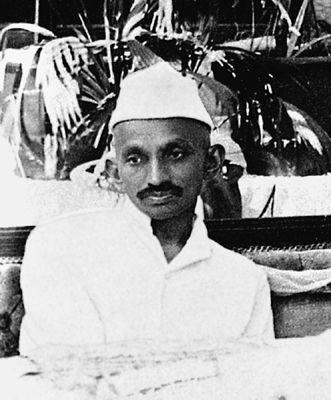

Soon-to-be Congress leader, 1920

(photo credit i6.1)

Three months later, in December 1920,

Shaukat Ali took the precaution of rounding up a flying force of burly “volunteers,” Muslims uncommitted to nonviolence, to face down any anti-Gandhi demonstrators at the annual Congress meeting, held that year in the Marathi-speaking city of Nagpur in central India. The so-called volunteers weren’t needed. Skepticism about noncooperation was still being voiced, but political opposition to Gandhi had melted away. His own example and relentlessness in argument, his mounting hold on the broader population and solid support from Muslims, all combined to make his leadership unassailable. The Nagpur Congress dutifully adopted Gandhi’s draft of a new constitution, extending the movement’s reach down to the villages for the first time, at least on paper. In another first engineered by him, it adopted the abolition of untouchability as a national goal. Swaraj would be impossible without it, Gandhi repeatedly said, but in fact the noncooperation campaign targeted two “wrongs” specifically attributed to the British—the threat to the Khilafat and their failure to punish those responsible for the Amritsar massacre. Untouchability might be, in Gandhi’s words, a “putrid custom,” but it was a Hindu wrong, an

urgent issue, no doubt, but one without any obvious place on an agenda designed to rouse as many Indians as possible to nonviolent resistance to the colonial power.

There was one conspicuous dissenter.

Mohammed Ali Jinnah was heckled when he referred drily in a speech to “Mister” rather than “Mahatma” Gandhi.

He left the Congress after Nagpur, never to return, predicting that Gandhi’s mass politics would lead to “complete disorganization and chaos.” His departure, scarcely noted at the time, opened a tiny fissure in the nationalist ranks. It would become a gaping cleavage after orthodox Muslim elements drifted away from the movement with the

waning of the Khilafat agitation. At this stage, it was not the nationalist goals of the Congress that had disillusioned Jinnah; he was still a convinced nationalist, an earnest believer in Hindu-Muslim reconciliation. Yet he was more a skeptic than a supporter of the Khilafat agitation. The readiness of Hindus—notably Gandhi—to exploit it was part of what alienated him.

At the start of 1921, the sway that the Anglicized Bombay lawyer Jinnah would come to have over India’s Muslims could hardly have been foreseen, even by him. It was Muhammad Ali who then captured their imaginations, and Ali was still bound to the Mahatma. Understatement wasn’t Ali’s style. “

After the Prophet, on whom be peace, I consider it my duty to carry out the commands of Gandhiji,” he declared. (The one-syllable suffix, as we’ve noted, is a common Indian way of showing respect for an elder or sage. Even today, in conversation, Gandhi is commonly referred to as “Mahatmaji” or “Gandhiji.”) For a time Muhammad Ali gave up eating beef as a gesture to Gandhi and all Hindus. Then, campaigning side by side with Gandhi across India, he took to wearing

khadi

, the homespun cloth the Mahatma embraced as a cottage industry, a means to

swadeshi

, or self-reliance, and, in the expanding Gandhian vision, as a mass self-employment scheme for village India and, therefore, its salvation. The

weaving and wearing of khadi (sometimes called

khaddar

) would not only feed spinners, handloom operators, and their families; it would enable India to boycott imported cloth from British mills and thus stand as another form of noncooperation. The bearded

maulana

—an honorific given to a man learned in Islamic law—not only wore khadi; he became an evangelist for the

charkha

, or spinning wheel, in front of Muslim audiences. “

We laid the foundation of our slavery by selling off the spinning wheel,” Muhammad Ali preached. “If you want to do away with slavery, take up the wheel again.” His support for such Gandhian tenets inevitably aroused criticism from

fellow Muslims.

Ultimately, the maulana had to defend himself against charges of “being a worshipper of Hindus and a Gandhi-worshipper.”

The preservation of the caliphate remained Muhammad Ali’s most urgent cause, but his readiness to stand with Gandhi on issues that meant little to Muslims—spinning and even cow protection—became a kind of validation of the Mahatma’s rhetorical leaps, his constant juggling and merging of seemingly unconnected campaigns in an attempt to establish a stable common ground for Hindus and Muslims. Noncooperation was the most serious challenge the Raj had faced, and Gandhi was the movement’s undisputed leader. But then the big tent of Hindu-Muslim unity he’d erected began to sag and, here and there, collapse as violence between the two communities, an endemic phenomenon on the subcontinent, appeared to give the lie to all the vows and pledges that had been offered up in India on behalf of the soon-to-exit caliph in Constantinople. The impressive coalition Gandhi had built and inspired was proving to be jerry-built.

By August 1921, a still hopeful Gandhi had to acknowledge that some Hindus were “apathetic to the Khilafat cause” and that it was “not yet possible to induce Mussulmans to take interest in swaraj except in terms of the Khilafat.”