Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (24 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

Soon he was having to amend, if not swallow, such high-flown words as dissenters like P. S. Aiyar pointed out how far short of the legal equality for which Gandhi had once struggled his “final settlement” now fell. What had been true before the last campaign remained true afterward: not only would Indians still be without political rights, but they’d still require permits to travel from one South African province to another; still not be allowed to settle in the

Orange Free State or expand their numbers in the Transvaal, where they’d still have to register under what Gandhi once decried as the “Black Act”; and they would still be subject to a tangle of local laws and regulations saying where they could own land or set up businesses. Nothing in the Indian Relief Act relieved the situation of indentured laborers still under contract who’d been the main body of strikers and marchers.

Nevertheless, the indenture system itself was clearly on its last legs. Natal had stopped importing contract laborers from India as early as 1911. The only way to keep the system going, then, was to persuade those still working off their indentures to sign new contracts when their

five-year commitments were up. Now the head tax no longer figured in such deals, no longer hung over the heads of the indentured. It may be said that Gandhi deserved a measure of credit for India’s eventual decision in 1917 to shut the system down altogether by halting the shipment of indentured laborers to island colonies like

Fiji and

Mauritius, which had continued recruiting them after South Africa stopped, that his campaigns in South Africa had helped force the Raj’s hand by arousing indignation among Indians. But the end of the indenture system hadn’t ever been one of the declared aims of those campaigns.

In a farewell letter to South African Indians, Gandhi conceded there were unmet goals, which he listed as the right to trade, travel, or own land anywhere in the country.

These could be achieved, he said, within fifteen years if Indians “cultivated” white public opinion. On political rights, his farewell letter looked to no distant horizon. This was a subject to be shelved. “

We need not fight for votes or for freedom of entry for fresh immigrants from India,” it advised. “My firm conviction is that passive resistance is infinitely superior to the vote,” he told the

Transvaal Leader

. Speaking here was the Gandhi of

Hind Swaraj

who frankly scorned the parliamentary institutions for which most Indian nationalists thought they were fighting.

Finally, he had to concede that the “final settlement” was not really final. While “it was final in the sense that it closed the great struggle,” he rephrased himself, awkwardly blurring the operative adjective, “it was not final in the sense that it gave to Indians all that they were entitled to.”

Smuts, who’d allowed himself to hope that he’d shelved the “Indian question” for the foreseeable future, considered Gandhi’s reformulation a betrayal of their understanding. Gandhi couldn’t express himself with his usual plainness on the question of how final the “final settlement” was because his “truth,” in this instance, wasn’t simple: the struggle had to end because he was leaving; he’d gotten all he could get. No one said it in so many words, but his departure was part of the deal.

White public opinion continued to harden, and Gandhi’s rosy forecasts proved far off the mark. The situation of Indians in South Africa got worse, not better, after he turned his attention to India. They were no better than second-class citizens and often less than that. Under apartheid, Indians were more relentlessly ghettoized and segregated than ever before, though never as severely oppressed and discriminated against as Africans. It took sixty years before they could travel freely in the only country nearly all of them had ever known, more than seventy

years before the last restriction on Indian landholding had been repealed. Equal political rights came eventually—a full century after Gandhi first sought them. In the years immediately following his departure, the white government dangled promises of free passage and bonuses to induce Indians to follow him home.

Between 1914 and 1940, nearly forty thousand took the bait. Immigration had been halted, but the number of Indians continued to rise by natural increase. And naturally, then, the vast majority had only faint hand-me-down memories of the mother country. In 1990, as the apartheid system was collapsing, the Indian population of South Africa was estimated to have passed one million. In

Nelson Mandela’s first cabinet, four of the ministers were Indian.

Though the future for the next several generations of South African Indians would prove bleak, the leader himself was almost free. His very tentative plan had been to sail directly to India with an entourage of about twenty and settle in Poona (now spelled Pune) in western India so as to be near the ailing Gopal Krishna Gokhale.

They had an understanding that Gandhi would keep a perfect silence on Indian issues for an entire year (as Gandhi put it, “keep his ears open and his mouth shut”). Gandhi now offered to nurse Gokhale and serve him as secretary. But Gokhale headed for Europe, specifically Vichy, in hopes that the waters there might be good for his failing heart. He asked Gandhi to meet him in London.

All he had to do before sailing for Southampton was complete a round of farewells. In Johannesburg, Mrs. Thambi Naidoo, who’d had the courage to go to the mines in Natal to appeal to the indentured mine workers to strike before Gandhi arrived on the scene, was said to have fallen over in a faint when her husband rose at a dinner and asked his old comrade-not-in-arms to adopt the four Naidoo sons and take them with him to India.

She’d not been consulted.

Gandhi thanked the “old jailbirds” for their “precious gift.” As his departure day neared, the indentured laborers with whom he’d marched became a preoccupation. He ended his farewell letter to the Indians of South Africa by penning these words above his signature: “

I am, as ever, the community’s indentured laborer.” In

Durban, he addressed indentured laborers as “brothers and sisters,” then pledged: “

I am under indenture with you for all the rest of my life.”

Speaking for the last time to his most loyal supporters, the

Tamils of Johannesburg, Gandhi concluded by dwelling on matters of caste. The Tamils had “shown so much pluck, so much faith, so much devotion to duty and such noble simplicity,” he said. They’d “sustained the struggle for the last eight years.” But after all that had been acknowledged, there was “one thing more.” He knew that they had carried over caste distinctions from India. If they “drew those distinctions and called one another high and low and so on, those things would be their ruin. They should remember that they were not high caste and low caste but all Indians, all Tamils.”

It’s impossible at this distance to know what had prompted this admonition on that occasion in that setting, this hauling into the open of a question even Gandhi had mostly allowed to recede for much of his time in South Africa. Had some Tamils on the great march, or even at this farewell gathering, shown their fear of ritual pollution? Or was he thinking ahead to what he would face in India? The exact connections are hard to pin down, but in a more general sense they seem obvious. For Gandhi, the phenomenon of indentured labor, a system of semi-slavery, as he branded it, had fused in his South African years with that of

caste discrimination. Whatever the underlying demographic facts showing the proportions of high caste, low caste, and untouchable among the indentured, these were no longer two things in his mind but one, a hydra-headed social monster that still needed to be taken on.

Finally, on the dock in Cape Town, as he was about to board the SS

Kinfauns Castle

on July 18, 1914, he put a hand on Hermann Kallenbach’s shoulder and told his well-wishers: “I carry away with me not my blood brother, but my European brother. Is that not sufficient earnest of what South Africa has given me, and is it possible for me to forget South Africa for a single moment?” They traveled third-class. Kallenbach brought with him two pairs of binoculars to use on deck. Gandhi, seizing on them as a gross self-indulgence, a backsliding into luxury by his friend, tossed them overboard. “

The Atlantic,” Rajmohan Gandhi, his grandson, writes, “was enriched.” Fatefully, the

Kinfauns Castle

docked the day after the outbreak of a world war. Kallenbach moved with the Gandhis into a boardinghouse for Indian students and, in preparation for a new life with Gandhi in India, tried to concentrate on his Hindi and Gujarati studies. Gandhi sent off letters to Pretoria, New Delhi, and Whitehall, searching for a chink in a bureaucratic wall that threatened to keep him from realizing his dream of having the Jewish architect at his side in India. No one was willing or able to authorize a German passport

holder to take up residence there in wartime. The viceroy wouldn’t run “the risk.” Gandhi delayed his own departure, but still the door stayed slammed. Eventually, Kallenbach was detained in a camp for enemy aliens on the Isle of Man, only to be returned to East Prussia in a prisoner swap in 1917. It was 1937 before the two men met again. “

I have no Kallenbach,” Gandhi lamented in his fifth year back in India.

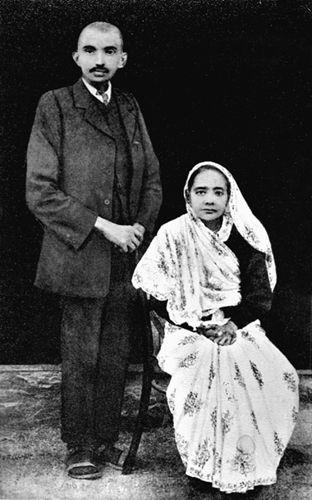

The Gandhis leaving South Africa

(photo credit i5.5)

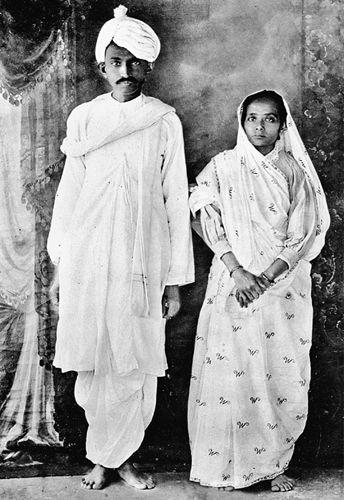

Six months later arriving in Bombay

(photo credit i5.6)

INDIA

WAKING INDIA

G

ANDHI HAD TAKEN A VOW

to spend his first year back in India readjusting to the swirl of Indian life. He’d promised his political mentor, Gokhale, that he’d make no political pronouncements in that time, take no sides, plunge into no movements. He’d travel the land, establish contacts, make himself known, listen, and observe. In loftier terms, he could be seen as trying to embrace as much of the illimitable Indian reality as he could. That proved to be quite a lot, more than any other political figure on the Indian scene had ever attempted.

Welcomed at first as an outsider, he became an itinerant guest of honor at civic luncheons and tea parties, hailed wherever he landed for his struggles in South Africa. His standard response was to protest, with becoming but not overly insistent modesty, that the “real heroes” on that other subcontinent had been the indentured laborers, the poorest of the poor, who had continued striking even after he’d been jailed.

He was more “at home” with them, he claimed in the first of these talks, than he was with the audience he was now facing, Bombay’s political elite and smart set. In obvious ways, it was a questionable claim, but it described Gandhi, from his first pronouncements in India, as a figure focused on the masses. It was also about as provocative as he allowed himself to be over the course of 1915, his first year home. He could have taken Gokhale’s death, just five weeks after that speech, as a release from his vow but refrained from advancing anything like a leadership claim of his own. But then, with his vow expiring in the first days of 1916, he made it plain that he had drawn some conclusions. “India needs to wake up,” he told yet another civic reception, this one in the Gujarati town of Surat.

“Without an awakening, there can be no progress. To bring it about in the country, one must place some program before it.”