Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (21 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

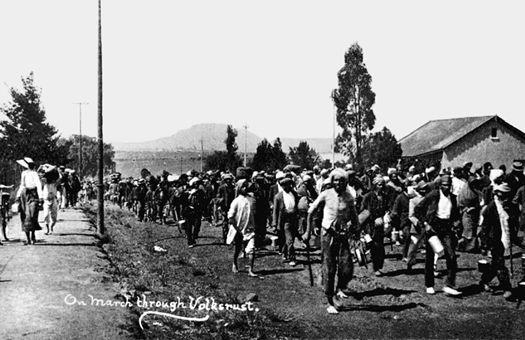

After the strikes, possibly in Durban

(photo credit i5.2)

He was not therefore a prisoner of events when he arrived in Newcastle on October 17, 1913. For the first time in his life, he found himself the leader of a mass movement. In Durban recently,

Hassim Seedat, a lawyer whose avocations include the study of Gandhi’s life and the collection of Gandhi materials, showed me a photograph of Gandhi as he disembarked that day. In it, the advocate turned leader is once again in Indian dress as he’d last been in Zanzibar, ten months earlier, bidding farewell to the homeward-bound Gokhale. The point of the costume change was to stress his identification with the indentured by adopting their garb. Hermann Kallenbach, his architecture practice now on hold, was there to greet him. He’d arrived the day before and had already gone on mine visits with Thambi Naidoo.

Natal’s attorney general reported that “a Jew Kallenbach … appears to be agitating.”

Gandhi immediately called for the walkout to be extended to collieries still in operation. The strikes quickly spread beyond the mines.

GANDHI CAUSES TROUBLE

, a headline over a

Reuters dispatch from Newcastle announced the next morning on the front page of

The Natal Witness

of Pietermaritzburg. “

A peculiar position has arisen here,” the dispatch began. “Hotels are without waiters and the mines are without labor.”

As the message spread beyond the two collieries that had already shut down, the roster of closed mines lengthened: Ballengeich, Fairleigh, Durban Navigation, Hattingspruit, Ramsey, St. George’s, Newcastle, Cambrian, and Glencoe. Within a week, all nine had been at least partly crippled by the walkout of indentured Indian mine workers. Two thousand strikers were believed to be waiting for their leader’s next command.

Most of the strikers were still in mine compounds, still being fed by

their increasingly anxious employers, still refusing to work. The strike next spread to Durban, where most services halted as indentured Indian bellmen, waiters, and sweepers, municipal menials of all sorts, stopped working. Thambi Naidoo was eventually arrested in a railway barracks in the process of enlisting even more indentured workers, threatening the shipment of coal to the gold mines and ports.

For a week, Gandhi himself was a self-propelled whirlwind, in constant motion from meeting to meeting, rally to rally, riding up and down the rail line he’d had his first fateful venture on in 1893. From Newcastle he traveled to Durban, where he faced a meeting on October 19 of restive Indian businessmen who made up the leadership of the Natal Indian Congress, the organization he once spearheaded, whose charter he’d single-handedly drafted, in whose name he’d sent all his early pleadings to colonial and imperial authorities. Frightened by the radical turn in Gandhi’s movement that his call to the indentured seemed to represent, the Congress passed what amounted to a motion of no-confidence, effectively expelling him. (A Gandhian rump soon regrouped as the

Natal Indian Association.) The leader had lost the support of most, though not all, of the Muslim traders who’d been his original backers, but he had little time now to mend fences.

Not surprisingly, it was P. S. Aiyar, the maverick editor of

African Chronicle

, who gave doubts about Gandhi’s new course their most cantankerous expression. “

Any precipitate step we might take in regard to the £3 tax,” he wrote with some foresight, “will not be conducive to improving the lot of these thousands of poor, half-starving people.” Aiyar urged Gandhi to call a national conference of South African Indians and heed any consensus on tactics it reached. Gandhi brushed the suggestion aside, saying he could accept the idea only so long as the result didn’t conflict with his conscience. This was too much for Aiyar. “We are not aware,” he erupted, “of any responsible politician in any part of the globe making such a stupid reply.” In effect, he said, Gandhi was presenting himself as “such a soul of perfection … [that his] superior conscience was pervading everywhere.”

No such sideline mutterings could slow Gandhi now. From Durban he shot back to Newcastle to tour some mine compounds, then scooted off to Johannesburg to rally white supporters, then went back again to Durban to face the owners of the mines. In six days, he spent at least seventy-two hours on trains. Everywhere, in speeches and written statements, he held out hope for an early end to the disruptions, even as his lieutenants worked to draw more indentured laborers into the still

spreading protest. The aims of the strikers, soothing passages in his written statements and speeches seemed to say, couldn’t be more modest; all the government needed to do was honor its pledge to banish the head tax, and fix the marriage law while they were at it. The workers were not striking for improved working conditions, he told the mine owners. The quarrel was not with them. Nor was it political. “

Indians do not fight for equal political rights,” he declared in a communiqué to

Reuters really meant for the authorities. “They recognize that, in view of existing prejudice, fresh immigration from India should be strictly limited.”

Despite all these signals and assurances, some of the mine executives voiced their deepest fear: that in addition to calling out his indentured countrymen, he’d seek, finally, to widen the stoppage by involving African workers. Gandhi denied having any such intention. “

We do not believe in such methods,” he told a reporter from

The Natal Mercury

.

John Dube’s

Ilanga

, reacting to the Indian strikes, slyly took note of white fears that Africans might follow this example. The first of several commentaries ended with a Zulu expression that can be translated, “We wish you the best, Gandhi!” or even, “Go for it, Gandhi!” Later, when it seemed likely that the agitation might gain some privileges denied Africans from a white Parliament simultaneously engaged in passing the egregious Natives Land Act, an undertone of resentment crept in.

By October 26, the leader had landed back in the coalfields.

All the women he’d dispatched to the area to win over the indentured had by then been arrested and sentenced to prison terms of up to three months, including his wife—along with scores of strikers identified by mine supervisors as “ringleaders,” many of whom would eventually be deported back to India—but an unfazed and completely focused leader was now ready to stay put with the strikers, to take over as field commander of what

The Star

, in a small headline, sneeringly mislabeled

MR. GHANDI’S ARMY

. In the next eleven days, until he himself was finally locked up on November 11, Gandhi would have his most prolonged and intense engagement with indentured laborers in his two decades in South Africa.

Within a day of his return to Newcastle, Gandhi hit on a tactic for bringing the conflict to a head. It involved forcing the authorities to contemplate mass arrests, far beyond the capacity of the prisons to hold those it detained. With this end in view, Gandhi urged the miners to leave the compounds and court arrest by marching across the Transvaal border at Volksrust. It was “improper,” he said, for them to be consuming

the rations of the mining companies when they had no intention of working until the head tax had been abolished. Another point probably counted for more but was left unstated: as long as the strikers were at the mines, there was a danger they could be sealed off in the compounds, limiting the possibility of communication and further mass action. On October 28, the first batch of marchers set out from Newcastle in the direction of the provincial border. The next day Gandhi himself led another two hundred from the

Ballengeich mine.

The procession, according to a tabulation he made later, reached five hundred, including sixty women, voicing religious chants as they marched: “Victory to Ramchandra!” “Victory to Dwarkanath!” “Vande Mataram!” Ramchandra and Dwarkanath were other names for the gods Rama and Krishna, heroes of the great Hindu epics. The last cry meant “Hail, Mother!” or, more specifically, Mother India, fusing high-flown religious and political

connotations. “

They struck not as indentured laborers but as servants of India,” Gandhi wrote. “They were taking part in a religious war.”

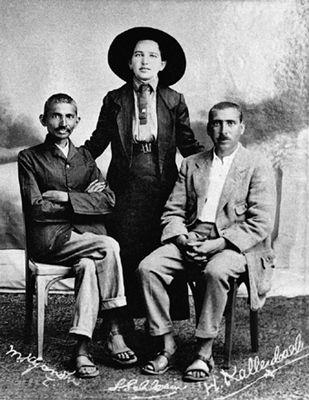

With Kallenbach, during

1913

strikes. Gandhi’s secretary, Sonja Schlesin, center

.

(photo credit i5.3)

By November 2, about two thousand miners and other indentured laborers had assembled at Charlestown, the Natal railway terminus, where the young Gandhi had boarded a stagecoach on his first journey to the Transvaal in 1893. Charlestown is thirty-four miles from Newcastle, mostly uphill, sometimes steeply.

Here a reporter for the

Sunday Times

found Gandhi in shirtsleeves in “the evil-smelling backyard of a tin shanty … sitting on an upturned milk case.” Next to him was a galvanized tub “full of an unsavory concoction which I took to be soup,” also sacks containing hundreds of bread loaves. The future Mahatma, working with “incredible rapidity,” was serving as quartermaster, cutting the loaves into three-inch hunks, then, according to this description, digging with his thumb a small hole into each hunk, which he then filled with coarse sugar as the men filed by in successive batches of a dozen strikers each.

It’s a picture to fix in the mind:

Gandhi, in the thick of his struggle, feeding his followers—described by another reporter on the scene as “consisting mostly of the very lowest castes of Hindus,” plus “the merest smattering of Mohammedans”—with his own hands. That a certain proportion of the strikers (maybe 20 percent, maybe more) were once considered untouchable in the Tamil villages from which they originally hailed is no longer, for Gandhi, something to be remarked upon. In his own mind, feeding them one by one in this way is basic logistics, not a display of sanctity. But for however many hundreds or thousands who received their food directly from his hands, he set a new standard for Indian leadership, for political leadership anywhere.

Later he wrote that he’d made serving food in Charlestown his “sole responsibility” because only he could persuade the strikers that portions had to be tiny if all were to eat. “Bread and sugar constituted our sole ration,” he said.

On November 5, he tried to get through to Smuts in Pretoria by phone in order to give him one last chance to renew his pledge on the tax. By then, Smuts was flatly denying that there had ever been such a pledge. Gandhi was curtly rebuffed by the minister’s private secretary. “

General Smuts will have nothing to do with you,” he was told. Then and now, the provincial border consisted of a little stream on the edge of Volksrust. (Under majority rule, names have changed. What was Natal is now KwaZulu-Natal; that portion of the Transvaal is now Mpumalanga.) The geography of this hinterland was familiar to Gandhi, who’d

been arrested in 1908, at this same point, for crossing the same provincial border without a permit.

On the morning of November 6, shortly after dawn, he set out from Charlestown with 2,037 men, 127 women, and 57 children. Gandhi told them that their destination was Tolstoy Farm, a distance of about 150 miles. A small police detachment was waiting for them at the border, but the “pilgrims,” as Gandhi had taken to calling them, swarmed across. Volksrust’s Afrikaners, who’d threatened to fire on the marchers, looked on passively as the procession passed through the town in regular ranks. Their first encampment was eight miles down the road. There, that night, Gandhi was arrested and taken back to Volksrust to appear before a magistrate who granted the retired barrister’s professionally argued request for bail. The sequence of arrest, arraignment, and bail was repeated the next day, so twice in two days he was able to rejoin the marchers. On November 9, with the procession already past the Transvaal town of Standerton, more than halfway to Tolstoy Farm, their leader was arrested for a third time in four days. Denied bail this time, he was hauled back to Natal where, two days later in Dundee, yet another coal-mining town with a British antecedent, he was found guilty in a small whitewashed courtroom—still in use in the postapartheid era—on three counts relating to his having led indentured laborers out

of their mine compounds and out of the province. As always, Gandhi eagerly pleaded guilty to each charge. The sentence—welcomed by Gandhi, who was never truer to his principles than when he found himself in the dock—was nine months of hard labor.