Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (13 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

There’s another Gandhi who later became a regular visitor at the Ohlange Institute, stopping by now and then on his daily walks. That Gandhi also got to know Isaiah Shembe, called by his followers the Prophet. In 1911 the Prophet founded the Nazareth Church—the largest movement among Zulu Christians, with more than two million adherents today—at Ekuphakameni, which lies between Inanda and Phoenix. (The Nazareth Church was called independent, meaning it was unaffiliated to any white denomination.) Shembe had a bigger impact on South Africa, it can be argued, than the founder of the Phoenix Settlement ever had. The other Gandhi, the one who took the

trouble to cultivate the acquaintance of these two significant African leaders, was Manilal, the mainstay of Phoenix after his father returned to India. When John Dube died in 1946 at seventy-five, the headline on his obituary in

Indian Opinion

read

A GREAT ZULU DEAD

. “

To us at the Phoenix Settlement from the days of Mahatma Gandhi,” the obituary said, “he has been a kindly neighbor.”

Sparse as this record is, the names Gandhi, Dube, and Shembe are hallowed today as a kind of Inanda troika, if not trinity, by the publicists and popular historians responsible for weaving a teachable heritage for the new South Africa out of the disparate movements that struggled into existence under oppressive white rule. The fact that three leaders of such consequence emerged in rural Natal in the same decade, within an area of less than two square miles, is too resonant with possibilities to be overlooked. It has to be more than a coincidence. And so we find the man who became the new South Africa’s third president elected by universal franchise, Jacob Zuma, celebrating “

the solidarity between the Indians and Africans” that came into being in Inanda. “What is also remarkable about the history of the Indo-African community in this area is the link that existed between three great men: Gandhi, John Langalibalele Dube and the prophet Isaiah Shembe of the Nazareth Church.” A tourist brochure urges visitors to follow the “Inanda Heritage Route” from Gandhi’s settlement to the Dube school and finally to Shembe’s church. (“Inanda where there is more history per square centimeter than anywhere in South Africa!” the brochure gushes, making no allusion to the sad, sometimes alarming state of what might otherwise be seen as a hard-pressed rural slum, except for the telltale caution that it not be visited without “a guide who knows the area well.”)

On my last visit to Inanda, banners stamped with Dube’s face were streaming from lampposts on the Kwa Mashu Highway, which cuts through the district, alternating with lampposts bearing Gandhi banners. Such sanctification of their imagined alliance rests on little more than the political convenience of the moment and a wispy oral tradition.

Lulu Dube, the last surviving child of the Zulu patriarch, grew up with the notion that her father kept in touch with Gandhi. “In fact, they were friends, they were neighbors and their mission was one,” she said in a chat on the veranda of Dube’s house, which was declared a national monument at the time of the first democratic election, then left to rot (to the point that eighty-year-old Lulu, fearful of a roof collapse, had moved into a trailer nearby). Born sixteen years after Gandhi left the country, she’s at best a link in a chain, not a witness. Ela Gandhi, keeper

of her grandfather’s flame in Durban as head of the

Gandhi Trust, inherited a similar impression. She was raised at Phoenix but decades after her grandfather departed. She was only eight when he was killed. A member of the African National Congress, she’s aware that, politically and historically, this is treacherous ground, so she chooses her words with care. “They were each concerned with dignity, particularly the dignity of their own people,” she said of the two men on the banners.

What the real history, as opposed to heritage mythmaking, seems to disclose is a deliberate distancing of each other by Gandhi and John Dube, a recognition, on rare occasions, that they might have common interests but a determination to pursue them separately. If there could ever have been a possibility of their making common cause, it may well have been stalled for a generation by Gandhi’s calculated reaction to a spasm of Zulu resistance in 1906—the year after they met—that was instantly characterized as a “rebellion” and brutally suppressed by Natal’s white settlers and colonial authorities.

The immediate provocation for the rising was a new head tax on “natives,” called a poll tax, and the severe penalties imposed on those who failed to pay up promptly. The broader provocation was a sense among Zulus—those still bound by tradition and those adapting to imported ways and faiths—that they were losing what was left of their land and autonomy. Numbers as much as race always had to be factored into these South African conflicts. Altogether the Zulus of Natal outnumbered the whites by about ten to one in that era (outnumbered the whites and Indians combined by about five to one). Gandhi’s instant reflex, as at the time of the Anglo-Boer War seven years earlier, had been to side with English-speaking whites who identified themselves with British authority in their struggle with Afrikaans-speaking whites who resisted it. Here again he offered to raise a corps of stretcher bearers—another gesture of Indian fealty to the empire, which in his view was the ultimate guarantor of Indian rights, however circumscribed they proved in practice. It was a line of reasoning few Zulus were likely to appreciate.

The story isn’t a simple one. Gandhi and Dube, each in his own way, were men of divided loyalties at the time of what came to be known as the Bhambatha Rebellion. Martial law was declared by trigger-happy colonial whites confronting Zulus armed mainly with assegais, or spears, before anything like a rebellion got under way. The spark was a face-off in early February between a group of protesting Zulu artisans from a

small independent church and a police detachment sent to arrest its leaders. One of the policemen pulled a revolver, spears were thrown, and before the smoke cleared, two of the officers had been killed. The protesters were then rounded up and twelve of them sentenced to death. The British cabinet tried at first to have the executions postponed, but the condemned men were lined up at the edge of freshly dug graves and shot on April 2. A few days later, a chief named Bhambatha, who was being sought for refusal to pay the tax, took to the deepest, thorniest bush in the hills of Zululand with some 150 warriors. A thousand troops were sent in hot pursuit, homesteads were raked with machine-gun fire, shelled, and then burned. More warriors took to the hills. Against this background, under the leadership of the man who would one day be called a mahatma, the Indian community offered its support to the governing whites in the fight against the so-called rebels. The least temperate of his many justifications for this stand is worth quoting at length, for it’s revealing on several levels:

For the Indian community, going to the battlefield should be an easy matter; for, whether Muslim or Hindu, we are men with profound faith in God … We are not overcome by fear when hundreds of thousands die of famine or plague in our country. What is more, when we are told our duty, we continue to be indifferent, keep our houses dirty, lie hugging our hoarded wealth. Thus, we live a wretched life, acquiescing in a long, tormented process ending in death. Why then should we fear the death that may overtake us on the battlefield? We have much to learn from what the whites are doing in Natal. There is hardly any family from which someone has not gone to fight the Kaffir rebels.

Obviously, what we have here is a rant. Gandhi’s irony is out of control; his inclination to scold undermines his desire to persuade. He has lost the thread of his argument about duty and citizenship. What comes across is revulsion, barely contained anger over the cultural inertia of his own community, its resistance to the social code he hopes to inculcate. If it offers nothing else, he seems to feel, the battlefield promises discipline.

The war posed a different set of conflicts for John Dube, the Congregational minister seeking to arm young Zulus not with spears but with the Protestant work ethic and basic skills that could win them a foothold in a trading economy. The rebels were, on the other hand, his people, and in the final stages of the conflict it was the chiefdom from which he descended that was attacked. The Christian in Dube, not to mention the pragmatist, could not endorse the rising, but the mercilessness of the

repression shook his faith in the chances for racial peace. Cautiously, in the columns of his newspaper, he questioned the heavy-handedness of the whites. Soon he was summoned to appear before the governor and warned that the martial law regulations applied to him and his paper. Somewhat chastened, he later wrote that the grievances of the rebels were real but “at a time like this we should all refrain from discussing them.”

What was said to be the severed head of

Chief Bhambatha had been displayed and the rebellion all but crushed by June 22, when Gandhi finally left

Durban for the struggle for which he’d been beating the drums in the columns of

Indian Opinion

for two months. This time the community had managed to restrain its enthusiasm for what he proposed as a patriotic duty and opportunity.

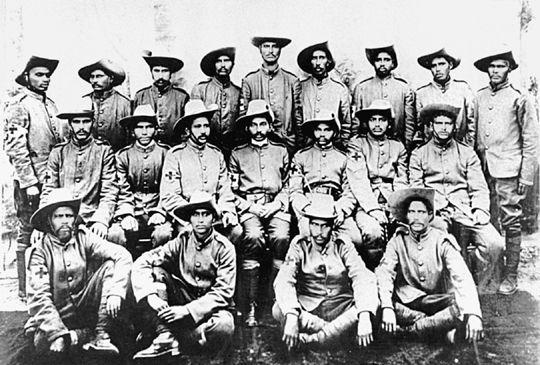

Gandhi had the rank of sergeant major but a much smaller band of stretcher bearers under his nominal command than he’d had at the start of the Anglo-Boer War: nineteen as opposed to eleven hundred in the earlier conflict; of the nineteen, thirteen were former indentured laborers; this time just four of twenty, counting Gandhi himself, could be classed as “educated.”

In the next few weeks, in the sporadic final clashes of the conflict, the colonial troops were told to take no prisoners. What Gandhi and his men got to witness were the consequences of the mopping up, the worst part of

the repression. At this stage of the conflict, there were few white wounded. Mostly the Indians ended up treating Zulu prisoners with terrible suppurating lacerations, not warriors with bullet wounds, but villagers who’d been flogged beyond submission.

Sergeant Major Gandhi with stretcher bearers, 1906

(photo credit i3.2)

Gandhi later wrote that the suffering Zulus, many of whom had been untreated for days, were grateful for the ministrations of the Indians, and maybe that was so. White medics wouldn’t touch them. But back at Phoenix, roughly forty miles from these scenes, Gandhi’s relatives and followers were seized by the fear that the Zulus in their neighborhood would rise against them in retaliation for the choice he’d made. He’d deposited Kasturba and two of his four sons there before leaving for the so-called front. “

I do not remember other things but that atmosphere of fear is very vivid in my mind,” Prabhudas Gandhi, a cousin who was a youngster at the time, would later write. “Today when I read about the Zulu people’s rebellion, the anxious face of Kasturba comes before my eyes.” No reprisals materialized, but signs of Zulu resentment over Gandhi’s decision to side with the whites were not lacking. Africans would not forget, said an article reprinted in another Zulu newspaper,

Izwi Labantu

, “that Indians had volunteered to serve with the English savages in Natal who massacred thousands of Zulus in order to steal their land.” That article was by an American.

Izwi

offered no comment of its own.

But it did say: “The countrymen of Gandhi … are extremely self-centered, selfish and alien in feeling and outlook.”

In London, an exile Indian publication called

The Indian Sociologist

, which tacitly supported terrorist violence in the struggle for Indian freedom, found Gandhi’s readiness to join up with the whites at the time of the Zulu uprising “disgusting.”

As the Zulu paper implied, Gandhi’s own outlook may have initially been alien and, in that sense, self-centered. But he was profoundly moved by the evidence of white brutality and Zulu suffering that he witnessed. Here again is

Joseph Doke, his Baptist hagiographer: “

Mr. Gandhi speaks with great reserve of this experience. What he saw he will never divulge … It was almost intolerable for him to be so closely in touch with this expedition. At times, he doubted whether his position was right.” The biographer seems to hint unwittingly at taboos of untouchability that Sergeant Major Gandhi’s small band had to overcome. “

It was no trifle,” he writes, for these Indians “to become voluntary nurses to men not yet emerged from the most degraded state.” Eventually, Gandhi did divulge what he saw—in his

Autobiography

, composed two decades after the event, and in conversations in his last

years with his inner circle. “

My heart was with the Zulus,” he then said.

As late as 1943, during his final imprisonment,

Sushila Nayar tells us, he was still recounting “the atrocities committed on the Zulus.”

“What has Hitler done worse than that?” he asked Nayar, a physician who was attending his dying wife and himself. Gandhi, who’d tried writing to Hitler on the eve of world war in an attempt to soften his heart, never quite realized, or at least acknowledged, that the führer represented a destructive force beyond anything he’d experienced.