God's Battalions (2 page)

Authors: Rodney Stark,David Drummond

Many superb historians have devoted their careers to studying aspects of the Crusades.27 I am not one of them. What I have done is synthesize the work of these specialists into a more comprehensive perspective, written in prose that is accessible to the general reader. However, I have been careful to fully acknowledge the contributions of the many experts on whom I have depended, some in the text and the rest in the endnotes.

The history of the Crusades really began in the seventh century when armies of Arabs, newly converted to Islam, seized huge areas that had been Christian.

©

Werner Forman / Art Resource, NY

I

N WHAT CAME TO BE KNOWN

as his farewell address, Muhammad is said to have told his followers: “I was ordered to fight all men until they say ‘There is no god but Allah.’”

1

This is entirely consistent with the Qur’an (9:5) : “[S]lay the idolaters wherever ye find them, and take them [captive], and besiege them, and prepare for them each ambush.” In this spirit, Muhammad’s heirs set out to conquer the world.

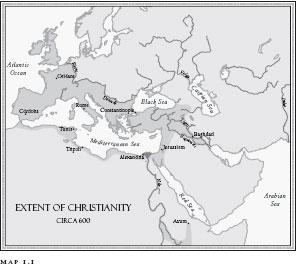

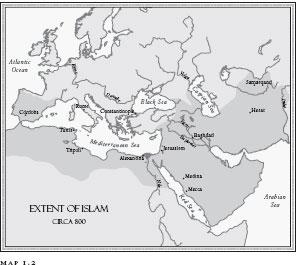

In 570, when Muhammad was born, Christendom stretched from the Middle East all along North Africa, and embraced much of Europe (see map 1.1). But only eighty years after Muhammad’s death in 632, a new Muslim empire had displaced Christians from most of the Middle East, all of North Africa, Cyprus, and most of Spain (see map 1.2).

In another century Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Crete, and southern Italy also came under Muslim rule. How was this accomplished? How were the conquered societies ruled? What happened to the millions of Christians and Jews?

THE CONQUESTS

Before he died, Muhammad had gathered a military force sufficient for him to contemplate expansion beyond Arabia. Foreign incursions had become increasingly attractive because Muhammad’s uniting the desert Bedouin tribes into an Arab state eliminated their long tradition of imposing protection payments on the Arab towns and villages as well as ending their freedom to rob caravans. So, attention turned to the north and east, where “rich spoils were to be won, and warriors could find glory and profit without risk to the peace and internal security of Arabia.”

2

Raids by Muhammad’s forces into Byzantine Syria and Persia began during the last several years of the Prophet’s life, and serious efforts ensued soon after his death.

In typical fashion, many historians have urged entirely material, secular explanations for the early Muslim conquests. Thus, the prominent Carl Heinrich Becker (1876–1933) explained that the “bursting of the Arabs beyond their native peninsula was…[entirely] due to economic necessities.”

3

Specifically, it is said that a population explosion in Arabia and a sudden decline in caravan trade were the principal forces that drove the Arabs to suddenly begin a series of invasions and conquests at this time. But the population explosion never happened; it was invented by authors who assumed that it would have taken barbarian “Arab hordes”

4

to overwhelm the civilized Byzantines and Persians. The truth is quite the contrary. As will be seen, the Muslim invasions were accomplished by remarkably small, very well led and well organized Arab armies. As for the caravan trade, if anything it increased in the early days of the Arab state, probably because the caravans were now far more secure.

A fundamental reason that the Arabs attacked their neighbors at this particular time was that they finally had the power to do so. For one thing, both Byzantium and Persia were exhausted by many decades of fighting one another, during which each side had suffered many bloody defeats. Equally important is that, having become a unified state rather than a collection of uncooperative tribes, the Arabs now had the ability to sustain military campaigns rather than the hit-and-run raids they had conducted for centuries. As for more specific motivations, Muhammad had seen expansion as a means to sustain Arab unity by providing new opportunities, in the form of booty and tributes, for the desert tribes. But most important of all, the Arab invasions were planned and led by those committed to the spread of Islam. As Hugh Kennedy summed up, Muslims “fought for their religion, the prospect of booty and because their friends and fellow tribesmen were doing it.”

5

All attempts to reconstruct the Muslim invasions are limited by the unreliability of the sources. As the authoritative Fred Donner explained, early Muslim chroniclers “assembled fragmentary accounts in different ways, resulting in several contradictory sequential schemes,” and it is impossible to determine which, if any, is more accurate.

6

Furthermore, both Christian and Muslim chronicles often make absurdly exaggerated claims about the size of armies—often inflating the numbers involved by a factor of ten or more. Fortunately, generations of resourceful scholars have provided more plausible statistics and an adequate overall view of the major campaigns. The following survey of Muslim conquests is, of course, limited to those prior to the First Crusade.

Syria

The first conquest was Syria, then a province of the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire). Syria presented many attractions. Not only was it close; it was the most familiar foreign land. Arab merchants had regularly dealt with Syrian merchants, some of whom came to the regular trade fairs that had been held in Mecca for generations. Then, too, Syria was a far more fertile region than Arabia and had larger, more impressive cities, including Damascus. Syria also presented a target of opportunity because of its unsettled political situation and the presence of many somewhat disaffected groups. After centuries of Byzantine rule, Syria had fallen to the Persians in about 611, only to be retaken by Byzantium in about 630 (two years before Muhammad’s death). During their rule the Persians destroyed the institutional basis of Byzantine rule, and when they were driven out a leadership vacuum developed. Moreover, Arabs had been migrating into Syria for centuries and had long been a primary source of recruits for the Byzantine forces. In addition, some Arab border tribes had long served as mercenaries to guard against their raiding kinsmen from the south. However, when Byzantium regained control of Syria, the emperor Heraclius, burdened with enormous debts, refused to reinstate the subsidies paid to these border tribes—an action that alienated them at this strategic moment.

7

The many Arab residents of Syria had little love for their Roman rulers, either. Hence, when the Islamic Arab invaders came, many Arab defenders switched sides during the fighting. Worse yet, even among the non-Arabs in Syria, “the Byzantine rule was so deeply hated that the Arabs were welcomed as deliverers.”

8

And no one hated and feared the Greeks more than the many large Christian groups such as the Nestorians, who had long been persecuted as heretics by the Orthodox bishops of Byzantium.

The first Muslim forces entered Syria in 633 and took an area in the south without a major encounter with Byzantine forces. A second phase began the next year and met more determined resistance, but the Muslims won a series of battles, taking Damascus and some other cities in 635. This set the stage for the epic Battle of Yarm k, which took place in August 636 and lasted for six days. The two sides seem to have possessed about equal numbers, which favored the Muslim forces since they were drawn up in a defensive position, forcing the Greeks to attack. Eventually the Byzantine heavy cavalry did manage to breach the Arab front line, but they were unable to exploit their advantage because the Muslims withdrew behind barriers composed of hobbled camels. When the Byzantines attacked this new line of defense they left their flanks exposed to a lethal attack by Muslim cavalry. At this point, instead of holding fast, the Greek infantry mutinied and then panicked and fled toward a ravine, whereupon thousands fell to their deaths below. Shortly thereafter, the shattered Byzantine army abandoned Syria.9 Soon the Muslim caliph established Damascus as the capital of the growing Islamic empire (the word

k, which took place in August 636 and lasted for six days. The two sides seem to have possessed about equal numbers, which favored the Muslim forces since they were drawn up in a defensive position, forcing the Greeks to attack. Eventually the Byzantine heavy cavalry did manage to breach the Arab front line, but they were unable to exploit their advantage because the Muslims withdrew behind barriers composed of hobbled camels. When the Byzantines attacked this new line of defense they left their flanks exposed to a lethal attack by Muslim cavalry. At this point, instead of holding fast, the Greek infantry mutinied and then panicked and fled toward a ravine, whereupon thousands fell to their deaths below. Shortly thereafter, the shattered Byzantine army abandoned Syria.9 Soon the Muslim caliph established Damascus as the capital of the growing Islamic empire (the word

caliph

means “successor,” and the title

caliph

meant “successor to Muhammad”).

Persia

Meanwhile, other Arab forces had moved against the Persian area of Mesopotamia, known today as Iraq. The problem of unreliable Arab troops also beset the Persians just as it had the Byzantines: in several key battles whole units of Persian cavalry, which consisted exclusively of Arab mercenaries, joined the Muslim side, leading to an overwhelming defeat of the Persians in the Battle of al-Q disyyah in 636.

disyyah in 636.

The Persians had assembled an army of perhaps thirty thousand, including a number of war elephants. The Muslim force was smaller and not as well armed but had a distinct positional advantage: a branch of the Euphrates River across their front, a swamp on their right, and a lake on their left. Behind them was the desert. The fighting on the first day was quite exploratory, although a probing advance by the war elephants was repulsed by Arab archers. The second day was more of the same. But on the third day the Persians mounted an all-out offensive behind their elephant combat teams. Again they were met with a shower of arrows, and the two leading elephants were wounded. As a result, they stampeded back through the other elephants, which followed suit, and the whole herd stomped their way back through the Persian ranks. As chaos broke out, the Arab cavalry charged and the battle was won—with immense Persian losses.

10