God's Battalions (22 page)

Authors: Rodney Stark,David Drummond

Clearly, the military orders needed huge European incomes in order to sustain their commitments in the East. So long as that mission was sustained, their immense wealth and power in Europe went unchallenged. But in 1291, with the fall of the last Christian foothold in Palestine and the massacres that ensued, the Templars no longer had an unquestionable mandate and soon became vulnerable to those who coveted their wealth and resented their power—most particularly King Phillip of France, who had Grand Master Jacques de Molay and other leading Templars burned as heretics on March 18, 1314.

KNIGHTS HOSPITALLERS

It all began with a hospital founded around 1070 to nurse wounded and sick pilgrims in Jerusalem. Initially, those staffing the hospital were not members of a recognized religious order, although they may have worn distinctive clothing and might have taken “some sort of religious vows.”

51

At some point they began referring to theirs as the Hospital of St. John, but there is very little known of its early days—although elaborate myths were later generated to help with fund-raising. Following the crusader conquest of Jerusalem, reliable references to the hospital begin to appear. It was an enormous undertaking, open to everyone, and able to accommodate about two thousand patients. Not only that; it accommodated its patients, including the desperately poor, in luxury that not even many of the rich enjoyed: a separate feather bed for everyone, and lavish meals.

52

Soon those in charge became as concerned about escorting pilgrims safely on the way from the coast to Jerusalem as they were with treating the wounded who made it to the city. Another military order was born.

How the transformation took place “remains a mystery.”

53

All we know is that they began to take over castles and provide them with garrisons, to wear black robes with a white cross on their breasts, and to otherwise appear as rivals to the Templars during the 1120s. Their participation in the major battles of the era also was noted, and it is estimated that they soon had as many knights in the Holy Land as did the Templars, albeit this amounted to only about three hundred men.

54

Officially known as the Order of St. John, the Knights Hospitallers also equaled the Templars in terms of their fighting abilities and the casualties they suffered. But when driven from the Holy Land, the Hospitallers did not withdraw to Europe, but only to Rhodes, whence they continued to fight the Muslims. And when driven from Rhodes, they took over Malta and there repelled repeated Muslim attacks—despite being outnumbered by as much as forty thousand to six hundred.

Also like the Templars, the Hospitallers assembled a vast amount of property in Europe and thereby became involved in financial affairs and money lending, although on a far smaller scale than the Templars. That they continued to be engaged in military resistance to Islam gave them a protective legitimacy that prevented the political conspiracy that overwhelmed the Templars. Indeed, now known as the Knights of Malta, the Hospitallers still exist.

55

CONCLUSION

The raison d’être of the military orders was the defense of the kingdom of Jerusalem, and they played a leading role in that task. That part of their stories is best told as a facet of the more general effort to protect the kingdom—an effort that also involved the secular knights of the kingdom and the periodic arrival of new crusading armies from Europe.

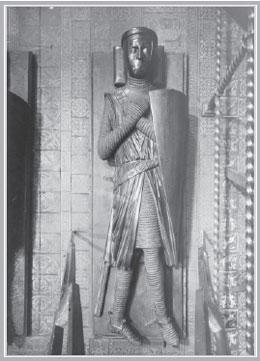

Although Europe continued to send additional crusading armies to the Holy Land, the burden of defense fell mainly on the knightly orders as commemorated in the marble tomb of a Knight Templar in London. His large shield indicates that he fought as an infantryman.

©

Foto Marburg / Art Resource, NY

T

HE CRUSADER KINGDOMS

were never at peace, nor could they have been. As Jonathan Riley-Smith explained, “for ideological reasons, peace with the Muslim world was unattainable.”

1

Temporary treaties were possible, but, given the doctrine of jihad (holy war), no lasting peace could be achieved except by surrender.

In keeping with jihad, at all times there were raids from Muslim-garrisoned cities within the crusader kingdoms and frequent probing attacks from the Muslim rulers across their borders. For more than forty years these threats were successfully repelled with the help of the military orders and the constant flow of knightly pilgrims, many of whom stayed on to fight for a time—sometimes for as long as several years. But this standoff was too good to last.

In the autumn of 1144, Count Joscelin II, ruler of the county of Edessa, formed an alliance with the Ortoqid Turks and led his army east to campaign against the Seljuk Turks led by Imad al-Din Zengi. But Zengi outmaneuvered them and attacked the city of Edessa, now poorly defended. On Christmas Eve, Zengi’s troops broke into the city, and those inhabitants who were not slain were sold into slavery. In the wake of this disaster, Count Joscelin fled to Turbessel, from where he was able initially to hold that portion of his realm west of the Euphrates. In 1150, on a journey to Antioch, Joscelin got separated from his escort and fell into Muslim hands. Zengi had Joscelin’s eyes put out and locked him in a dungeon, where he died nine years later.

THE SECOND CRUSADE

News of the fall of Edessa reached the West in early 1145 via returning pilgrims and came “as a terrible shock” to Christians in Europe. “For the first time they realized that things were not well in the East.”

2

Consequently, Pope Eugene III issued a bull,

Quantum praesecessores

, calling for a new Crusade. The pope’s message aroused little interest. However, the pope soon had the wisdom to recruit Bernard of Clairvaux to his cause, and when the most powerful, persuasive, and revered man in Europe began to preach a Second Crusade, things began to happen.

One thing that happened was that Bernard convened a gathering of the French nobility at Vézelay in Burgundy. “The news that Saint Bernard was going to preach brought visitors from all over France…Very soon the audience was under his spell. Men began to cry for Crosses” to sew on their chests.

3

Bernard was prepared for this and had brought many woolen crosses. The decisions to take the cross were not spontaneous; the people “knew why they were there.”

4

Even so, Bernard ran out of crosses and tore up his cloak to make more.

Among those who volunteered that day was King Louis VII of France. He had long been planning a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, but Bernard convinced him he should lead an army of crusaders. Consequently, Louis, together with his queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and a select group of princes and nobles, prostrated themselves at Bernard’s feet and accepted the cross. Louis was twenty-five at this time and was only beginning his “long career of energetic ineffectiveness,” as Christopher Tyerman so aptly put it.

5

Next, Bernard went to Germany, where he convinced King Conrad III and his nephew Frederick Barbarossa to take the cross. Unlike Louis, Conrad was in his early fifties and had considerable military experience. In fact, he had twice previously campaigned in the Holy Land. As in France, the German nobility flocked to hear Bernard, and again there was a public show of taking the cross by men who already had agreed to go.

Just as the First Crusaders were drawn from a closely knit network of family ties, the same was true of those who took the cross this time as well—especially among the French. Not only were most of the volunteers related to many other volunteers, but there were dense family ties to those who had gone on the First Crusade; the majority of the nobles who went had “crusading forefathers.”

6

Unfortunately, as enthusiasm for a new Crusade spread across Germany, it reignited the same anti-Semitism that had caused a rash of attacks on the Rhineland Jews at the start of the First Crusade. As pointed out in chapter 6, these attacks had been the work of a few, but they had set a pattern by directing attention to the issue of continuing to permit Jews to reject Jesus in a context where religious conformity was of growing concern. Even a few churchmen succumbed to this temptation. Abbé Pierre of the French monastery at Cluny pointed out, “What good is the good of going to the end of the world at great loss of men and money, to fight Saracens, when we permit among us other infidels who are a thousand times more guilty toward Christ than are the Mohammedans?”

7

Nevertheless, it was not in France, but only in the Rhine Valley, that massacres of Jews took place—once again in Cologne, Mainz, Metz, Worms, and Speyer.

8

In this instance, a Monk named Radulph helped stir up the anti-Semitic outbursts. But the death toll would have been far higher had it not been for the intervention of Bernard of Clairvaux. When word reached him about the attacks on Jews, Bernard rode as rapidly as he could to the Rhine Valley and ordered an end to the killings—and they ceased! His intervention was reported by Ephraim of Bonn, a Jewish chronicler:

Then the Lord heard our sigh…He sent after the evil priest a decent priest, a great man…His name was Abbot Bernard, from the city of Clairvaux…[who] said to them[,] “It is fitting that you go forth against Muslims. However, anyone who attacks a Jew and tries to kill him it is as though he attacks Jesus himself. My pupil Radulph who advised destroying them did not advise properly. For in the book of Psalms is written concerning the Jews, “Kill them not, lest my people forget.’” Everyone esteemed this priest as one of their saints…Were it not for the mercies of our Creator Who sent the aforesaid abbot…there would not have been a remnant or survivor among the Jews.

9

Historians have tended to skip the Second Crusade.

10

Jonathan Phillips’s 2007 book is the first “full treatment”

11

since Bernhard Kugler’s monograph, published in 1866. This neglect is nothing new. Otto of Freising, the respected historian who commanded a major German contingent that was annihilated during the Second Crusade, wrote that “since the outcome of the expedition, because of our sins, is known to all, we…leave this to be related by others elsewhere.”

12

Consequently, while all of the general histories of the Crusades give extensive coverage to the Battle of Dorylaeum in 1097, the second Battle of Dorylaeum in 1147 receives only a few sentences despite the fact that it was a far bloodier and much more decisive engagement.

It is a mistake to neglect the Second Crusade, because of two very important consequences: It gave a serious and long-lasting blow to the crusading movement in the West, undermining both confidence and commitment. And it restored Muslim confidence; after decades of defeats, usually by far smaller Christian forces, they now believed they could measure up.

The brief account that follows ignores the various “sideshows” to the Second Crusade involving the campaign against the Slavs and the conquest of Lisbon.

As a result of Bernard’s effective efforts, it had been agreed that the two most powerful monarchs of Europe would lead two great armies to the Holy Land, setting forth at about Easter 1147. As would be expected, the departures were delayed, and the Germans left in May, the French following in June. As might not have been expected, the two monarchs chose to follow the same route to Constantinople, going overland across Hungary and Bulgaria. Having been in the lead, the Germans reached the Byzantine capital on September 10. That arrival date reflected an army so burdened with camp followers and “substantial contingents of unarmed pilgrims taking advantage of the protection afforded by the military expedition” that it had traveled at less than ten miles a day—far slower than the armies of the First Crusade.

13

When the Germans reached Constantinople, they found they were not very welcome; had it been up to the Byzantines, there would not have been a Second Crusade. Indeed, just prior to the departure of the crusaders from Europe, the Byzantine emperor Manuel Comnenus had concluded a twelve-year treaty with the Seljuk sultan of Konya (Iconium), who would soon be at war with the crusaders. When the Europeans learned of this arrangement, it added to their already deep suspicions and antagonism towards the “perfidious Greeks.”

14

For his part, Manuel was deeply disturbed at having such a large and potentially unruly force camped near his capital. So, just as the emperor Alexius had pressured the First Crusaders to cross into Asia Minor, so, too, the emperor Manuel pressed the Germans to cross the Bosporus—adding substantially to the distrust and dislike the Europeans felt toward the Byzantines. Having crossed over, Conrad decided not to wait for the French but to push on to recover Edessa.

Given the size of his army—perhaps as many as thirty thousand bearing arms

15

—this was not a rash decision. Moreover, Conrad probably hoped that, once free to plunder the countryside, he could somewhat overcome his dire shortages of food and fodder; Emperor Manuel had promised supplies but failed to deliver them. So Conrad marched his army and a huge contingent of noncombatants to Nicaea. There he split his expedition, placing most of the noncombatants under the leadership of Otto, bishop of Freising, who followed the more westerly road through Philadelphia and on to the port of Adalia (whence they sailed to Tyre). Swarms of noncombatants—many of them elderly, most of them poor—were always a stressful drain and hindrance to the crusaders. Despite strenuous efforts to persuade them not to come, large numbers always showed up and had to be fed and protected, while greatly slowing the pace of the advance.

16

Meanwhile, moving along the same route followed by the First Crusaders, Conrad’s army marched down the road to Dorylaeum (see map 7.1, Chapter 7). Although the emperor had not sent any supplies, he did provide Conrad with a group of experienced Byzantine guides, whose purpose may have been to lead the crusaders to their destruction. Some modern historians doubt the claims by the crusaders that they had been betrayed by their guides, but no one challenges that the Byzantine guides did disappear during the night just prior to the Muslim ambush of the Germans.

In desperate need of provisions and especially short of water, the German crusaders reached the small Bathys River near Dorylaeum on October 25. The weary and thirsty troops broke ranks and scattered along the river to drink, and the knights dismounted and led their horses to the stream. At that moment “the whole Seldjuk army fell upon them…It was a massacre rather than a battle.”

17

Most of the German crusaders were killed, and Conrad was wounded. The king did manage to rally a remnant of perhaps two thousand troops and retreat to Nicaea, where the Greeks confronted them with “exorbitant prices for food.”

18

Then the French arrived and Conrad merged his small force with theirs, but he soon fell ill and was evacuated back to Constantinople.

The French had been greeted with an even more hostile reception from the Byzantines than had the Germans—so much so that they briefly entertained the idea of an attack on Constantinople. To avoid the dreadful route south that had helped defeat the Germans, Louis led his French army west toward the port of Ephesus with expectations that by remaining within Byzantine territory he would find the locals cooperative and receive supplies by sea from Emperor Manuel. But the locals were of no help, and no supplies came. Not surprisingly, the army became increasingly disorderly. To restore discipline to the march, Louis placed a Knight Templar in command of each unit of fifty. This paid big dividends when, despite the crusaders’ being in Byzantine territory, the Seljuk Turks, allied though they were to the emperor, attacked just beyond Ephesus. Some historians suggest that the emperor had conspired with the Turks;

19

in any event, the Muslims were routed by the French.

At this point Louis turned his forces eastward and headed for the port of Adalia, where he had been promised they would be met by a Byzantine fleet that would ferry them to a landing just west of Antioch. Of course, the fleet sent by the emperor was much too small to accommodate more than a fraction of the army. Some recent historians take this as additional evidence that Manuel “connived at their [the crusaders’] destruction.”

20

After making the best preparations he could, Louis sent the bulk of his army overland to Antioch while he, his court, and as many troops as could be accommodated boarded the ships. The overland march was hopeless. When it began, the horses already were dying by the hundreds and everyone faced starvation. Muslims harassed them along the way, killing all stragglers and foragers. Only a handful of those who set out reached Antioch.

Having sailed safely to Antioch, Louis went to Jerusalem to fulfill his vow for a pilgrimage. Conrad had recovered from his wounds and illness and was already in the Holy City, as were leaders of forces newly arrived from the West. A council of war was held in Acre during which the visiting Europeans and Baldwin III, king of the crusader kingdom of Jerusalem, agreed to attack Damascus. (No representatives of Antioch, Edessa, or Tripoli attended.) The plan had an excellent strategic basis but was tactically ill advised. After an abortive attempt at a siege, and having suffered substantial losses, the Christian forces gave up the attempt.

The Second Crusade was over. Boarding ships provided by the Normans from Sicily, the French king and his entourage headed for home—only to suffer a narrow escape when attacked by a Byzantine fleet. (The Normans and the Byzantines still were fighting over possession of southern Italy.) Of course, this further inflamed Western antagonism toward the Byzantines.