God's Battalions (7 page)

Authors: Rodney Stark,David Drummond

Meanwhile, the Normans had not lost interest in Muslim Sicily. In 1059, after Robert Guiscard, duke of southern Italy, had designated himself in a letter to Pope Nicholas II as “future [lord] of Sicily,”

49

the Norman plans for an invasion began to take shape. Guiscard was a remarkable man. The Byzantine princess Anna Comnena described him as “overbearing,” “brave,” and “cunning,” and as having a “thoroughly villainous mind.” She continued: “He was a man of immense stature, surpassing even the biggest men; he had a ruddy complexion, fair hair, [and] broad shoulders,” but was remarkably “graceful.”

50

In 1061 Guiscard, his brother Roger, and a select company of Normans made a night landing at Messina and in the morning found the city abandoned. Guiscard immediately had the city fortified and then formed an alliance with Ibn at-Tinnah, one of the feuding Sicilian emirs, and took most of Sicily before having to return to Italy to see after affairs there. He made several minor gestures toward expanding his control of part of Sicily but concentrated on overwhelming the remaining Byzantine strongholds in southern Italy, finally driving the Greeks out of southern Italy in 1071. The next year he returned to Sicily, captured Palermo, and soon took command of the entire island. In 1098 Robert Guiscard’s eldest son, Bohemond, led the crusader forces that took the city of Antioch and became the ruler of the princedom of Antioch. Then, in 1130, Guiscard’s nephew Robert II established the Norman kingdom of Sicily (which included southern Italy).

51

It lasted for only about a century, but Muslim rule never resumed.

CONTROL OF THE SEA

During the 1920s, the Belgian historian Henri Pirenne (1862–1935) gained international fame by claiming that the “Dark Ages” descended on Europe not because of the fall of Rome or the invasion of northern “barbarians,” but because Muslim control of the Mediterranean isolated Europe. He wrote: “The Mediterranean had been a Roman lake; it now became, for the most part, a Moslem lake,”

52

and, cut off from trade with the East, Europe declined into a backward collection of rural economies.

To support this claim Pirenne cited fragmentary evidence that overseas trade had declined sharply late in the seventh century and remained low until early in the tenth. Although Pirenne’s thesis was very influential for many years, eventually it lost plausibility as scholars discovered convincing evidence that the alleged decline in trade on which it rested had been greatly overstated. Perhaps there had been some interruptions of seaborne trade with the East during the first fifty years of Muslim expansion, but there is evidence that extremely active Mediterranean trade quickly resumed, even between western Europe and Islamic countries.

53

Oddly enough, historians have failed to pay much attention to the most fundamental and easily assessed of Pirenne’s assumptions: that Muslim sea power ruled the Mediterranean.

54

It is difficult to know how Pirenne came to this view. Perhaps he simply believed Ibn Khald n (1332–1406), who wrote that “the Muslims gained control over the whole Mediterranean. Their power and domination over it was vast. The Christian nations could do nothing against the Muslim fleets, anywhere in the Mediterranean. All the time the Muslims rode its waves for conquest.”

n (1332–1406), who wrote that “the Muslims gained control over the whole Mediterranean. Their power and domination over it was vast. The Christian nations could do nothing against the Muslim fleets, anywhere in the Mediterranean. All the time the Muslims rode its waves for conquest.”

55

Nevertheless, even with the advantages provided by possession of some strategically placed island bases, the Muslim fleet never ruled the waves.

Granted, soon after the conquest of Egypt the Muslims acquired a powerful fleet, and in 655 they defeated a Byzantine fleet off the Anatolian coast. But only twenty years later the Byzantines used Greek fire to destroy a huge Muslim fleet, and in 717 they did so again. Then, in 747 “a tremendous Arab armada consisting of 1,000 donens [galleys] representing the flower of the Syrian and Egyptian naval strength” encountered a far smaller Byzantine fleet off Cyprus, and only three Arab ships survived this engagement.

56

Muslim naval forces never fully recovered, in part because they suffered from chronic shortages “of ship timber, naval stores, and iron,” all of which the Byzantines had in abundance.

57

Hence, rather than the Mediterranean becoming a Muslim lake, the truth is that the eastern Mediterranean was a Byzantine lake, the Byzantine navy having become “the most efficient and highly trained that the world had ever seen, patrolling the coasts, policing the high seas and attacking the Saracen raiding parties whenever and wherever they might be found.”

58

It is true that the Muslims were able to sustain some invasions by sea in the western Mediterranean in the eighth and ninth centuries, far from the Byzantine naval bases, but by the tenth century they were driven to shelter by Western fleets as well as those of a renewed Byzantium.

Muslim naval weakness should always have been obvious. For one thing, the Muslims quickly realized that they must withdraw their fleets from open harbors, where they risked destruction from surprise attacks. Thus, for example, Carthage was abandoned, and the fleet stationed there was moved inland to Tunis and a canal dug to provide access to the sea. Being so narrow as to accommodate only one galley at a time, the canal was easily defended against any opposing fleet.

59

In similar fashion, the Egyptian fleet was removed from Alexandria and rebased up the Nile. While these were sensible moves, they also revealed weakness.

That the Muslims lacked control of the seas also was obvious in the ability of Byzantium to transport armies by sea with impunity—for example, their landing and supplying of the troops that drove Islam from southern Italy. Nor could the Muslim navies impede the very extensive overseas trade of the Italian city-states such as Genoa, Pisa, and Venice.

60

Indeed, in the eleventh century, well before the First Crusade, Italian fleets not only preyed on Muslim shipping but successfully and repeatedly raided Muslim naval bases along the North African coast.

61

Hence, during the Crusades, Italian, English, Frankish, and even Norse fleets sailed to and from the Holy Land at will, transporting thousands of crusaders and their supplies. Finally, as will be demonstrated in the next chapter, contrary to Pirenne’s thesis, Muslim sea barriers to trade could not have caused Europe to enter the “Dark Ages,” because the “Dark Ages” never took place.

CONCLUSION

All of these Christian victories preceded the First Crusade. Consequently, when the knights of western Europe marched or sailed to the Holy Land, they knew a lot about their Muslim opponents. Most of all, they knew they could beat them.

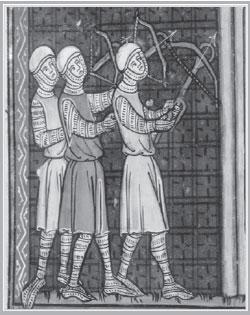

Contrary to frequent claims, Muslim technology lagged far behind that of the West. The knights shown here are armed with crossbows that were far more accurate and deadly than Muslim bows—Muslim arrows could seldom penetrate the chain-mail armor worn by these and most other crusaders, but very few Muslims had such armor.

©

British Library / HIP / Art Resource, NY

I

T HAS LONG BEEN

the received wisdom that while Europe slumbered through the Dark Ages, science and learning flourished in Islam. As the well-known Bernard Lewis put it in his recent study, Islam “had achieved the highest level so far in human history in the arts and sciences of civilization…[intellectually] medieval Europe was a pupil and in a sense dependent on the Islamic world.”

1

But then, Lewis pointed out, Europeans suddenly began to advance “by leaps and bounds, leaving the scientific and technological and eventually the cultural heritage of the Islamic world far behind them.”

2

Hence, the question Lewis posed in the title of his book:

What Went Wrong?

This chapter documents my answer to Lewis’s question:

nothing

went wrong. The belief that once upon a time Muslim culture was superior to that of Europe is at best an illusion.

DHIMMI

CULTURE

To the extent that Arab elites acquired a sophisticated culture, they learned it from their subject peoples. As Bernard Lewis put it, without seeming to fully appreciate the implications, Arabs inherited “the knowledge and skills of the ancient Middle east, of Greece, of Persia and of India.”

3

That is, the sophisticated culture so often attributed to Muslims (more often referred to as “Arabic” culture) was actually the culture of the conquered people—the Judeo-Christian-Greek culture of Byzantium, the remarkable learning of heretical Christian groups such as the Copts and the Nestorians, extensive knowledge from Zoroastrian (Mazdean) Persia, and the great mathematical achievements of the Hindus (keep in mind the early and extensive Muslim conquests in India). This legacy of learning, including much that had originated with the ancient Greeks, was translated into Arabic, and portions of it were somewhat assimilated into Arab culture, but even after having been translated, this “learning” continued to be sustained primarily by the

dhimmi

populations living under Arab regimes. For example, the “earliest scientific book in the language of Islam” was a “treatise on medicine by a Syrian Christian priest in Alexandria, translated into Arabic by a Persian Jewish physician.”

4

As in this example, not only did most “Arab” science and learning originate with the

dhimmis;

they even did most of the translating into Arabic.

5

But that did not transform this body of knowledge into Arab culture. Rather, as Marshall Hodgson noted, “those who pursued natural science tended to retain their older religious allegiances as

dhimmis,

even when doing their work in Arabic.”

6

That being the case, as the

dhimmis

slowly assimilated, much of what was claimed to be the sophisticated Arab culture disappeared.

Although not a matter of intellectual culture, Muslim fleets provide an excellent example. The problems posed for their armies by the ability of Byzantium to attack them from the sea led the early Arab conquerors to acquire fleets of their own. Subsequently, these fleets sometimes gave good account of themselves in battles against Byzantine and Western navies, and this easily can be used as evidence of Islamic sophistication. But when we look more closely, we discover that these were not really “Muslim” fleets.

Being men of the desert, the Arabs knew nothing of shipbuilding, so they turned to their newly acquired and still-functioning shipyards of Egypt

7

and the port cities of coastal Syria (including Tyre, Acre, and Beirut) and commissioned the construction of a substantial fleet. The Arabs also knew nothing of sailing or navigation, so they manned their Egyptian fleet with Coptic sailors

8

and their Persian fleet with mercenaries having Byzantine naval backgrounds. A bit later, when in need of a fleet at Carthage, the Muslim “governor of Egypt sent 1,000 Coptic shipwrights…to construct a fleet of 100 warships.”

9

While very little has been written about Muslim navies (itself suggestive that Muslim writers had little contact with them),

10

there is every reason to assume that Muslims never took over the construction or command of “their” fleets but that they continued to be designed, built, and sailed by

dhimmis.

Thus in 717, when the Arabs made their last effort against Constantinople by sea, a contributing factor in their defeat was “the defection to the Byzantine side of many of the Christian crews of Arab vessels.”

11

Finally, when an enormous Muslim fleet was sunk by Europeans off the coast of Lepanto in 1571, “the leading captains of both fleets were European. The sultan himself preferred renegade Italian admirals.”

12

Moreover, not only were the Arab ships copies of European designs; “[t]hey were built for the sultan by highly paid runaways,”

13

by “shipwrights from Naples and Venice.”

14

The highly acclaimed Arab architecture also turns out to have been mainly a

dhimmi

achievement, adapted from Persian and Byzantine origins. When Caliph Abd el-Malik had the great Dome of the Rock built in Jerusalem, and which became one of the great masterpieces attributed to Islamic art, he employed Byzantine architects and craftsmen,

15

which is why it so closely resembled the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

16

Similarly, in 762, when the caliph al-Mans r founded Baghdad, he entrusted the design of the city to a Zoroastrian and a Jew.

r founded Baghdad, he entrusted the design of the city to a Zoroastrian and a Jew.

17

In fact, many famous Muslim mosques were originally built as Christian churches and converted by merely adding external minarets and redecorating the interiors. As an acknowledged authority on Islamic art and architecture put it, “the Dome of the Rock truly represents a work of what we understand today as Islamic art, that is, art not necessarily made by Muslims…but rather art made in societies where most people—or the most important people—were Muslims.”

18

Similar examples abound in the intellectual areas that have inspired so much admiration for Arab learning. Thus, in his much-admired book written to acknowledge the “enormous” contributions of the Arabs to science and engineering, Donald R. Hill noted that very little could be traced to Arab origins and admitted that most of these contributions originated with conquered populations. For example, Avicenna, whom the

Encyclopaedia Britannica

ranks as “the most influential of all Muslim philosopher-scientists,” was a Persian. So were the famous scholars Omar Khayyám, al-Biruni, and Razi, all of whom are ranked with Avicenna. Another Persian, al-Khwarizmi, is credited as the father of algebra. Al-Uqlidisi, who introduced fractions, was a Syrian. Bakht-Ish ’ and ibn Ishaq, leading figures in “Muslim” medical knowledge, were Nestorian Christians. Masha’allah ibn Athar

’ and ibn Ishaq, leading figures in “Muslim” medical knowledge, were Nestorian Christians. Masha’allah ibn Athar , the famous astronomer and astrologer, was a Jew. This list could be extended for several pages. What may have misled so many historians is that most contributors to “Arabic science” were given Arabic names and their works were published in Arabic—that being the “official” language of the land.

, the famous astronomer and astrologer, was a Jew. This list could be extended for several pages. What may have misled so many historians is that most contributors to “Arabic science” were given Arabic names and their works were published in Arabic—that being the “official” language of the land.

Consider mathematics. The so-called Arabic numerals were entirely of Hindu origin. Moreover, even after the splendid Hindu numbering system based on the concept of zero was published in Arabic, it was adopted only by mathematicians while other Muslims continued to use their cumbersome traditional system. Many other contributions to mathematics also have been erroneously attributed to “Arabs.” For example, Thabit ibn Qurra, noted for his many contributions to geometry and to number theory, is usually identified as an “Arab mathematician,” but he was a member of the pagan Sabian sect. Of course, there were some fine Muslim mathematicians, perhaps because it is a subject so abstract as to insulate its practitioners from any possible religious criticism. The same might be said for astronomy, although here, too, most of the credit should go not to Arabs, but to Hindus and Persians. The “discovery” that the earth turns on its axis is often attributed to the Persian al-Biruni, but he acknowledged having learned of it from Brahmagupta and other Indian astronomers.

19

Nor was al-Biruni certain about the matter, remarking in his

Canon Masudicus

that “it is the same whether you take it that the Earth is in motion or the sky. For, in both cases, it does not affect the Astronomical Science.”

20

Another famous “Arab” astronomer was al-Battani, but like Thabit ibn Qurra, he, too, was a member of the pagan Sabian sect (who were star worshippers, which explains their particular interest in astronomy).

The many claims that the Arabs achieved far more sophisticated medicine than had previous cultures

21

are as mistaken as those regarding “Arabic” numerals. “Muslim” or “Arab” medicine was in fact Nestorian Christian medicine; even the leading Muslim and Arab physicians were trained at the enormous Nestorian medical center at Nisibus in Syria. Not only medicine but the full range of advanced education was offered at Nisibus and at the other institutions of learning established by the Nestorians, including the one at Jundishapur in Persia, which the distinguished historian of science George Sarton (1884–1956) called “the greatest intellectual center of the time.”

22

Hence, the Nestorians “soon acquired a reputation with the Arabs for being excellent accountants, architects, astrologers, bankers, doctors, merchants, philosophers, scientists, scribes and teachers. In fact, prior to the ninth century, nearly all the learned scholars in the [Islamic area] were Nestorian Christians.”

23

It was primarily the Nestorian Christian Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-‘Ibadi (known in Latin as Johannitius) who “collected, translated, revised, and supervised the translation of Greek manuscripts, especially those of Hippocrates, Galen, Plato, and Aristotle[,] into Syriac and Arabic.”

24

Indeed, as late as the middle of the eleventh century, the Muslim writer Nasir-i Khrusau reported, “Truly, the scribes here in Syria, as is the case of Egypt, are all Christians…[and] it is most usual for the physicians…to be Christians.”

25

In Palestine under Muslim rule, according to the monumental history by Moshe Gil, “the Christians had immense influence and positions of power, chiefly because of the gifted administrators among them who occupied government posts despite the ban in Muslim law against employing Christians [in such positions] or who were part of the intelligentsia of the period owing to the fact that they were outstanding scientists, mathematicians, physicians and so on.”

26

The prominence of Christian officials was also acknowledged by Abd al-Jabb r, who wrote in about 995 that “kings in Egypt, al-Sh

r, who wrote in about 995 that “kings in Egypt, al-Sh m, Iraq, Jaz

m, Iraq, Jaz ra, F

ra, F ris, and in all their surroundings, rely on Christians in matters of officialdom, the central administration and the handling of funds.”

ris, and in all their surroundings, rely on Christians in matters of officialdom, the central administration and the handling of funds.”

27