Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires (17 page)

Authors: Selwyn Raab

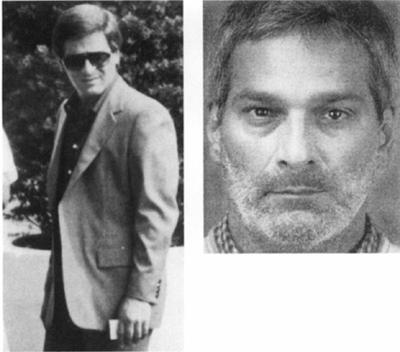

Ralph Scopo’s bugged conversations alerted the FBI to evidence for the Commission Case. A Colombo soldier, and laborers’ union president, Scopo was the bagman for shaking down concrete contractors at major construction projects.

(FBI Surveillance Photo)

Alphonse Persico, Carmine’s eldest son, talked about becoming a lawyer but became a Colombo capo. Carmine’s attempt to install “Little Allie Boy” as boss ignited an internal mob war. Allie Boy grew a beard while imprisoned for racketeering in the early 1990s and was indicted in 2004 for ordering the murder of a Colombo rival.

(Photos courtesy of the Federal Bureau of Investigation)

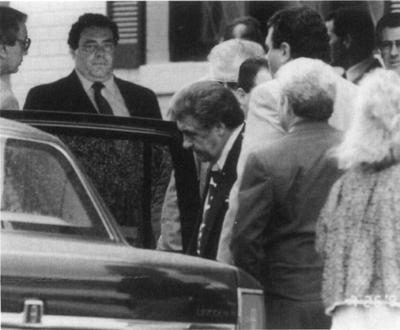

Surrounded by bodyguards and loyal followers, Victor “Little Vic” Orena enters his car during the Colombo War. Orena’s plan to seize power crumbled when he was convicted on RICO and murder charges and sentenced to life imprisonment.

(Photos courtesy of the Federal Bureau of Investigation)

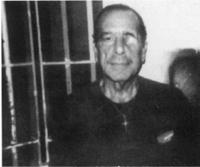

A warlord for the Persico faction, Gregory Scarpa was shot in the eye during the Colombo War when a narcotics deal went awry. After Scarpa died in prison of AIDS, the government disclosed that he had committed crimes while secretly a high-level FBI informer for thirty years.

(Photo courtesy of NYC Department of Correction)

Luciano sailed into exile on a cargo ship from a navy yard in Brooklyn on February 10, 1946. The night before, Frank Costello and several other mafiosi, using their ILA connections, slipped past guards to board the ship for a farewell dinner of lobster, pasta, and wine with their erstwhile boss. Lucky was shipped back to his native Sicilian village of Lercara Friddi, where he was given a royal welcome as a poor boy who had come back fantastically wealthy. Hundreds of villagers, unconcerned about his Mafia ties, cheered and waved American flags as he was driven to the town square in a police car. But Luciano had no nostalgic or pleasant memories of the primitive village; he soon left for Palermo and then Naples.

Luciano’s release created a damaging legacy for Dewey. Soon after the mobster’s departure, news stories were published exaggerating his wartime assistance to the government. The syndicated columnist and radio broadcaster Walter Winchell reported in 1947 that Luciano would receive the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award, for his secret services. Winchell was suspected of getting that hot tip from an acquaintance and neighbor in his apartment building—none other than Frank Costello.

Almost from the start, press allegations circulated that Dewey had sold Luciano his pardon. Finally, in 1953, while still governor, Dewey ordered a confidential inquiry by the state’s commissioner of investigation. In 1954 a 2,600-page report documented Luciano’s involvement with the navy without finding any wrongdoing by Dewey or the parole board in granting clemency.

Naval officials in Washington reviewed the report and once again were chagrined that their reliance on the Mafia would be exposed. Offering feeble excuses that the report would be a public-relations disaster for the navy and might damage similar intelligence operations in the future, the navy brass pleaded with Dewey to suppress the findings. Despite the harm to his reputation, Dewey complied with the navy’s request and buried the report in his personal papers. The essential facts about the Luciano episode remained confidential until they were made public by Dewey’s estate in 1977.

Before his death, Dewey confided to friends that Luciano’s thirty-year minimum sentence was excessive and that ten years—exactly what he served before clemency was granted—would have been sufficient for the crime of aiding and abetting prostitution. The former prosecutor was confident that Luciano had been an organized-crime mastermind. But Dewey’s odd comment about the harshness of the sentence buttressed the view of many independent observers that the trial evidence against Luciano had been flimsy, and that the main

witnesses against him, who later recanted, had been cajoled and pressured by Dewey’s insistent investigators.

Perhaps, in commuting the sentence, there was a tinge of a troubled conscience in Dewey’s concession that the sentence was overly severe. Was the former prosecutor acknowledging that he got the right man for the wrong crime?

Serene Times

Serene TimesW

hen it came to using World War II for personal benefit, Vito Genovese was a master. Moreover, before the fighting ended, he managed the tricky feat of aiding both the Axis and the Allied sides and enriching himself immensely.

Forced to flee the United States in 1937 to escape an impending indictment on an old Brooklyn murder case, Genovese, still an Italian citizen, planted himself in Naples. To keep in the good graces of Mussolini’s regime, he became an avid supporter of II Duce and, as a demonstration of his loyalty, contributed $250,000 for the construction of a Fascist Party headquarters near Naples. He further aided the dictator in wartime by using his American Mob connections to arrange a contract in New York: the assassination in January 1943 of Mussolini’s old foe Carlo Tresca, the antifascist refugee editor of

II Martello

(the Hammer).

For service rendered, Mussolini, the intransigent enemy of the Sicilian Mafia, awarded the American-trained gangster the title

Commendatore del Re

, a high civilian honor, an Italian Knighthood.

When the tide of war turned and the Allies invaded Italy in the summer of 1943, Genovese disavowed his fascist sympathies. Capitalizing on his literacy in English and his knowledge of American customs, he became an interpreter and adviser to the U.S. army’s military government in the Naples area. Don Vito

quickly resorted to doing what he knew best: conceiving criminal opportunities in any environment. Working out deals with corrupt military officers, Genovese became a black market innovator in southern Italy. Officers supplied him at military depots with sugar, flour, and other scarce items, which he transported in U.S. army trucks to his distribution centers. It was later learned that he laundered large sums of money through confidential Swiss bank accounts that he had established when he returned to Italy before the war.

In war-wracked and starving Italy, Don Vito was living in high style when Army Intelligence investigators dismantled the black market ring and arrested him in August 1944. Genovese tried to bribe his way out of trouble by dangling $250,000 in cash before an intelligence agent, Orange C. Dickey. The upright agent rejected the offer and in a background check learned of the Brooklyn warrant for Genovese’s arrest on a homicide indictment.

Genovese was extradited in June 1945. By the time he arrived in the United States, however, the homicide case against him had collapsed because of the strange death of a material witness in protective custody in Brooklyn. Prosecutors were counting on eyewitness evidence from an innocent cigar salesman named Peter LaTempa to corroborate the murder accusations against Genovese. Understandably worried about LaTempa’s safety on the streets before the trial, the DA’s office had him locked up in the Raymond Street jail. While behind bars, presumably for his own safety, LaTempa suffered a gallstone attack and was given what should have been prescription painkilling tablets. Several hours later, he was dead. The city medical examiner reported that the pills LaTempa swallowed were not the prescribed drugs and contained enough poison “to kill eight horses.” Although a witness in protective custody was murdered inside a city prison, no one was arrested for the crime or for involvement in an obvious conspiracy to silence the cigar salesman.

Burton Turkus, the lead prosecutor in the Murder Inc. cases, expressed the frustration of trying to solve Mob-ordered slayings and overcoming

omertà.

“There is only one way organized crime can be cracked,” he said. “Unless someone on the inside talks, you can investigate forever and get nowhere.”

A free man as a result of LaTempa’s death, Genovese was back in the top rung of the Mafia, ostentatiously flashing the wealth acquired in the New York rackets and the Italian black market. To signal his importance, he built an elaborately furnished mansion on the New Jersey shore in Atlantic Highlands, where he and his wife, Anna, dined on gold and platinum dishes.

Genovese’s return in 1946 was an unsettling event for Frank Costello.

Lucky Luciano was quarantined in Italy, and apparently had abdicated the title of boss of the borgata that he had founded. Now, after a decade of running the crime family, Costello faced a dangerous challenge from Genovese, who had considered himself the gang’s underboss and heir apparent to the throne when he abruptly hightailed it out of the country.

Like other members of his family, Costello was familiar with Genovese’s Machiavellian intrigues and savage inclinations. “If you went to Vito,” Joe Valachi noted, “and told him about some guy who was doing wrong, he would have this guy killed, and then he would have you killed for telling on this guy.”

Genovese spread the word that during his temporary exile, his crew had not been treated favorably by Costello and had not prospered as much as the rest of the family. Ever the diplomat, Costello arranged a truce with Genovese and his revived faction that left Costello as boss of the family. “Costello treated him with great respect,” recalled Ralph Salerno, the New York organized-crime expert. “Genovese was resentful because he had been ahead of Costello when he left the country and believed he should have been the boss. Instead Costello remained on top and he was just a capo.”