Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires (15 page)

Authors: Selwyn Raab

Following up on Lanza’s tip, Murray I. Gurfein, a top aide to Hogan, relayed the Navy’s request for Luciano’s cooperation to his lawyer, Moses Polakoff, and to Meyer Lansky, Luciano’s Jewish confederate. Through government intervention, Luciano was transferred from Dannemora to Great Meadow Prison in Comstock, New York, sixty miles north of Albany, a more convenient site for visits by Polakoff and Lansky. To convince Luciano of their good intentions and his importance to their plan, the government also allowed Frank Costello and Socks Lanza to meet with him in prison.

Before his conviction on prostitution charges, Luciano had few racketeering interests in the harbor. But members of his crime family and other Mafia borgatas, and Irish hoodlums who operated on the waterfront, owed him favors. He instructed Meyer Lansky to act as his middleman and to spread the message that he wanted everyone to cooperate and comply with Naval Intelligence requests. Because of Lansky’s long relationship with Luciano, none of the Mob controllers of the unions and other activities on the docks questioned the authenticity of his instructions.

Luciano had been in prison for six years and was ineligible for parole for another twenty-four years when the navy request came. He made it clear to his lawyer that he expected his aid to the government to lead to a sentence reduction.

But there was another thought in the back of his mind, and he stressed to Polakoff and Lansky that he wanted his cooperation kept secret. Never naturalized as a citizen, Lucky realized that he could be deported and feared that Mussolini loyalists in Italy might kill or assault him if his wartime assistance to the Allies was disclosed and the Fascists were still in power.

Before the July 1943 Allied invasion of Sicily, Luciano’s Mob helpers found several Sicilians who aided Naval Intelligence in preparing maps of Sicilian harbors, and digging up old snapshots of the island’s coastline. Press reports after the war that Luciano had managed to contact and instruct Sicilian Mafia leaders to assist in the invasion were absurd fabrications. Luciano was out of touch with the Sicilian Mafia, and neither they nor the American Cosa Nostra made any significant contributions to the Allied victory in Italy. Luciano’s influence provided limited help to the war effort. Mobsters obtained ILA union cards that allowed intelligence agents to work and mingle on the waterfront, and none of the unions called strikes or work stoppages that would have crippled the port. There were no acts of sabotage—but there had been none before Luciano’s intervention, and there is no evidence that any were ever planned by German agents or Nazi sympathizers.

Even before the war ended, Luciano tried to capitalize on his cooperation with Naval Intelligence. His 1943 appeal for a sentence reduction was rejected, but in the summer of 1945, as the war was ending, he again petitioned the governor for executive clemency, this time citing his assistance to the navy. Naval authorities, belatedly embarrassed that they needed and had recruited organized-crime assistance, refused to confirm Luciano’s claim. But the Manhattan DA’s office authenticated the facts, and the state parole board unanimously recommended to the governor that Luciano be released and immediately deported. That governor was Thomas E. Dewey, the former prosecutor who had sent Luciano to prison for a minimum of thirty years. In January 1946, Dewey granted Luciano executive clemency, with provisions that he be deported, and—if he reentered the country—that he be treated as an escaped prisoner and forced to complete his maximum sentence of fifty years.

“Upon the entry of the United States into the war,” Dewey said in a brief explanation for the release, “Luciano’s aid was sought by the Armed Services in inducing others to provide information concerning possible enemy attack. It appears that he cooperated in such effort, although the actual value of the information procured is not clear.”

Charles “Lucky” Luciano (center), the visionary godfather and designer of the modern Mafia, escorted by two detectives at a New York City court on June 18, 1936, where he was sentenced on compulsory-prostitution charges. Some experts believe Lucky was framed on the prostitution counts. Deported to Italy when his prison sentence was commuted, Lucky helped mastermind the Mafia’s flooding of heroin into America’s big cities.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

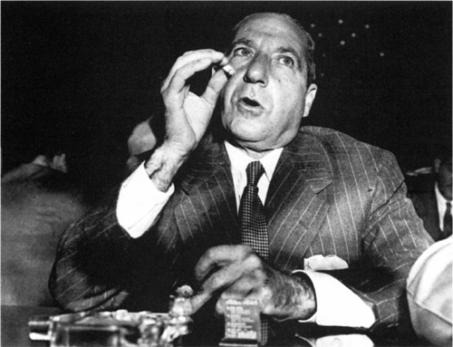

Debonair Mafia kingpin Frank Costello, who strived to pass as a legitimate businessman and liked to match wits with Congressional interrogators, smokes a cigarette while testifying before a Senate committee in 1950. Asked about his illegal gambling empire, Costello shrugged: “Maybe I don’t know about it.” He retired abruptly in 1957 as the boss of a major Mafia family after feared rival Vito Genovese put a contract out on his life.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

A rare photo of a smiling Vito Genovese taken shortly after he usurped the crown in 1957 from Frank Costello and became boss of a crime family that still bears his name. Vito had a reputation for treachery, including whacking his wife’s first husband to clear the way to marry the widow, and for escaping prison sentences. He was finally convicted in 1959 of narcotics trafficking and died in prison a decade later.

(Photo courtesy of Frederick Martens archive)

One of the original five godfathers, Joe Profaci, appears displeased at having his picture taken after being detained by state troopers at the Mafia’s aborted 1957 summit meeting in Apalachin, New York. Celebrated as the “Olive Oil King,” he was the largest importer of olive oil and tomato paste in the country and founded the Mafia gang in 1931 known today as the Colombo family. A mob boss for thirty years, Profaci never spent a day in an American jail, amassing a fortune from bootlegging, prostitution, and the numbers and loansharking rackets.

(Photo courtesy of Frederick Martens archive)

A dour Paul Castellano, then forty-five, also was picked up in the police raid at the Apalachin convention, along with more than fifty Mafia leaders from throughout the country. Nicknamed “Big Paul” when he became boss of the Gambino family, Castellano was at the 1957 conclave as an aide to his godfather and brother-in-law, Carlo Gambino.

(Photo courtesy of Frederick Martens archive)

One of the biggest catches at Apalachin was Carlo Gambino, shown in a 1934 Rogues’ Gallery photo. After engineering the 1957 barbershop assassination of an incumbent boss, Albert “Lord High Executioner” Anastasia, Don Carlo created the nation’s most powerful borgata, which still bears his name—the Gambino family.

(Photo courtesy of the New York City Police Department)

A ramrod-straight Big Paul Castellano, aka “the Pope,’ appears unperturbed after his arrest by the FBI in February 1985 as lead defendant in the watershed Commission Case. He was accused of being the boss of the Gambino family and a major figure on the Mafia’s Commission, or national board of directors.

(Photo courtesy of the Federal Bureau of Investigation)