Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (3 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

In the end, most shareholders suffered staggering losses as Enron’s stock price in 2000 plunged from over $80 per share (with a market capitalization exceeding $60 billion) to $0.25 nine short but painful months later. Some insiders, however, sold large parts of their holdings

before

the collapse. Enron’s chairman and former CEO, Ken Lay, and other top officials sold hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of stock in the months leading up to the crisis.

Legal Justice for Enron Executives—a Minor Consolation for Shareholders

On May 25, 2006, a jury returned guilty verdicts against Enron’s chairman, Ken Lay, and CEO, Jeffrey Skilling. Skilling was convicted on 19 of 28 counts of securities and wire fraud and sentenced to over 24 years in prison. Lay was tried and convicted on 6 counts of securities and wire fraud, but he died two months later while awaiting sentencing that could have locked him up for 45 years.

Investors should also have questioned how, despite sales growing tenfold over this period, profits failed to even double. The sales figures and their unprecedented annual rise year after year should have raised alarms for investors. Chapters 3 and 4 of this book will share some of Enron’s darkest secrets in how it inflated revenue without detection for all those years by using a little-understood method known as mark-to-market accounting and by improperly “grossing up” sales to give the illusion of being a much larger company.

Key Lesson:

When reported sales growth far exceeds any normal patterns, revenue recognition shenanigans may likely have fueled the increase.

ENRON: FINANCIAL SHENANIGANS IDENTIFIED

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigans

•

Recording Revenue Too Soon

•

Recording Bogus Revenue

•

Boosting Income Using One-Time or Unsustainable Activities

•

Employing Other Techniques to Hide Expenses or Losses

Cash Flow Shenanigans

•

Shifting Financing Cash Inflows to the Operating Section

•

Shifting Normal Operating Cash Outflows to the Investing Section

•

Inflating Operating Cash Flow Using Acquisitions or Disposals

•

Boosting Operating Cash Flow Using Unsustainable Activities

Key Metrics Shenanigans

•

Showcasing Misleading Metrics That Overstate Performance

•

Distorting Balance Sheet Metrics to Avoid Showing Deterioration

WorldCom: Most Brazen Creation of Fictitious Profit and Cash Flow

WorldCom Inc. began life in 1983 as the American telecommunications company Long Distance Discount Services (LDDS). In 1989, LDDS merged into a shell company called Advantage Companies in order to become publicly traded, and in 1995, LDDS changed its name to LDDSWorldCom.

Throughout WorldCom’s history, its growth came largely from making acquisitions. (As we will explain later, acquisition-driven companies offer investors some of the greatest challenges and risks.) The largest of these occurred in 1998 with the $40 billion acquisition of MCI Communications. Accordingly, the name was again changed, this time to MCI WorldCom. A few years later, the name was finally shortened to WorldCom.

The Accounting Games at WorldCom

Almost from the beginning, WorldCom used aggressive accounting practices to inflate its earnings and operating cash flows. One of its principal shenanigans involved making acquisitions, writing off much of the costs immediately, creating reserves, and then releasing those reserves into income as needed. With more than 70 deals over the company’s short life, WorldCom continued to “reload” its reserves so that they were available for future release into earnings.

This shenanigan would probably have been able to continue had WorldCom been allowed to acquire the much larger Sprint in a $129 billion deal announced in October 1999. Antitrust lawyers and regulators at the U.S. Department of Justice and their counterparts at the European Union disapproved of the merger, citing monopoly concerns. Without the acquisition, WorldCom “lost” the expected infusion of new reserves that it needed, as its prior ones had rapidly been depleted by being released into income.

Key Warning:

Acquisitive Companies

—Financial shenanigans often lurk at companies that grow predominantly by making acquisitions. Moreover, acquisition-driven companies often lack internal engines of growth, such as product development, sales, and marketing.

By early 2000, with its stock price declining and intense pressure from Wall Street to “make its numbers,” WorldCom embarked on a new and far more aggressive shenanigan—moving ordinary business expenses from its Statement of Income to its Balance Sheet. One of WorldCom’s major operating expenses was its so-called line costs. These costs represented fees that WorldCom paid to third-party telecommunication network providers for the right to lease their networks. Accounting rules clearly require that such fees be expensed and

not be capitalized

. Nevertheless, WorldCom removed hundreds of millions of dollars of its line costs from its Statement of Income in order to please Wall Street. In so doing, WorldCom dramatically understated its expenses and inflated its earnings, while duping investors. This trick continued quarter after quarter from mid-2000 through early 2002 until it was uncovered by internal auditors at WorldCom.

CEO Bernie Ebbers Spends Like a Drunken Sailor

With WorldCom regularly meeting Wall Street’s earnings targets, its stock price rose dramatically. CEO Bernie Ebbers sold large blocks of his stock to support other business ventures (timber) and his lavish lifestyle (yachting). As the stock declined in 2001 during the technology meltdown, Ebbers found some extra cash that he needed by borrowing against (i.e., margining) his stock holdings. As margin calls from brokers increased, Ebbers convinced the board of directors to give him corporate loans and guarantees in excess of $400 million. Ebbers had probably hoped that these loans would prevent the need for him to sell a substantial portion of his WorldCom stock, which would have further hurt the company’s share price. However, this strategy to prevent the stock price from collapsing ultimately failed, and Ebbers was ousted as CEO in April 2002, just months before the fraud was revealed.

The Collapse of WorldCom

Meanwhile, in early 2002, a small team of internal auditors at WorldCom, working on a hunch, were secretly investigating what they thought could be fraud. After finding $3.8 billion in inappropriate accounting entries, they immediately notified the company’s board of directors, and events progressed swiftly. The CFO was fired, the controller resigned, Arthur Andersen withdrew its audit opinion for 2001, and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) launched an investigation.

WorldCom’s days were numbered. On July 21, 2002, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the largest such filing in U.S. history at the time (a record that has since been overtaken by the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008). Under the bankruptcy reorganization agreement, the company paid a $750 million fine to the SEC and restated its earnings in an amount that defies belief. In total, the company reported an accounting restatement that exceeded $70 billion, including adjusting the 2000 and 2001 numbers from the originally reported gain of nearly $10 billion to an astounding loss of over $64 billion. The directors also felt the pain, having to pay almost $25 million to settle class-action litigation.

Postbankruptcy and the Fate of Bernie Ebbers

The company emerged from bankruptcy in 2004. Previous bondholders were paid 36 cents on the dollar, in bonds and stock in the new company, while the previous stockholders were wiped out completely. In early 2005, Verizon Communications agreed to acquire MCI for about $7 billion. Two months later, Ebbers was found guilty of all charges and convicted of fraud, conspiracy, and filing false documents. He was later sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Warning for WorldCom Investors—Evaluate Free Cash Flow

Investors would have found some clear warning signs in evaluating WorldCom’s Statement of Cash Flows (SCF), specifically, its rapidly deteriorating free cash flow. WorldCom manipulated both its net earnings and its operating cash flow. By treating line costs as an asset instead of an expense, WorldCom improperly inflated its profits. In addition, since it improperly placed those expenditures in the Investing rather than the Operating section of the SCF, WorldCom similarly inflated operating cash flow. While reported operating cash flow appeared consistent with reported earnings, the company’s free cash flow told the story.

Reported Cash Flow from Operations Looked Solid

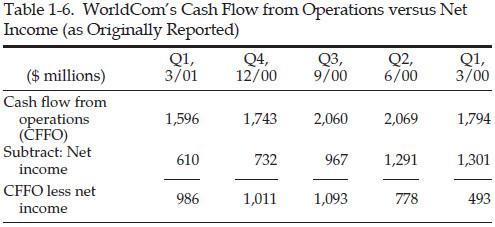

As shown in Table 1-6, WorldCom cleverly hid its problems from investors, as the cash flow from operations (CFFO) regularly exceeded net income. (Part 3 of this book shows how investors could have known that WorldCom’s CFFO was artificially inflated.)

Accounting Capsule: Free Cash Flow

Free cash flow measures the cash generated by a company, including the impact of cash paid to maintain or expand its asset base (i.e., purchases of capital equipment). Free cash flow typically would be calculated as follows:

Cash flow from operations

minus

capital expenditures

equals

free cash flow

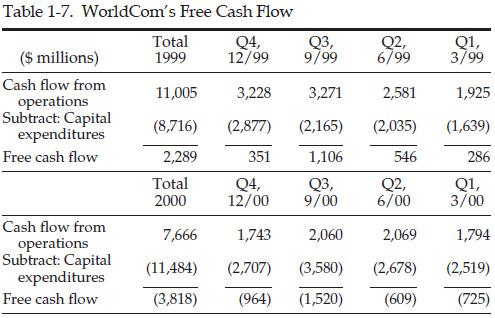

Free Cash Flow Told the Real Story

A key to uncovering WorldCom’s shenanigans required taking the analysis of cash flow a step further—computing its “free cash flow.” This metric removes line costs from cash flow, regardless of whether they are presented in the Investing or the Operating section of the SCF. Let’s examine Table 1-7, which gives free cash flow. During 1999, the period just before the company began capitalizing line costs, WorldCom generated almost $2.3 billion in free cash flow. Let’s contrast that to the following year, when World- Com experienced a $3.8 billion decline in free cash flow—a staggering deterioration of over $6.1 billion. Noting this dramatic and troubling turnabout, WorldCom investors should have concluded that the business was in deep trouble, fraud or no fraud.

Key Lesson:

When free cash flow suddenly plummets, expect big problems.

WORLDCOM: FINANCIAL SHENANIGANS IDENTIFIED

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigans

• Recording Bogus Revenue

• Shifting Current Expenses to a Later Period

• Employing Other Techniques to Hide Expenses or Losses

• Shifting Future Expenses to an Earlier Period

Cash Flow Shenanigans

• Shifting Normal Operating Cash Outflows to the Investing Section

• Inflating Operating Cash Flow Using Acquisitions or Disposals