Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (6 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

Be Particularly Alert When a Single Family Dominates Management and the Board

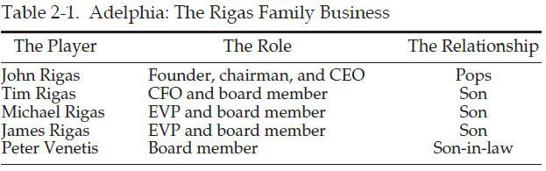

. You would have to search long and hard to find a public company with weaker checks and balances than Adelphia Communications. Members of founder John Rigas’s family made up a majority of the executive office and the board of directors, and they held a large percentage of the voting shares. Table 2-1 shows the family players, their roles, and the incestuous nature of the management team and the board.

Not surprisingly, this family management team was at the helm as a massive fraud that looted Adelphia and its investors of hundreds of millions of dollars was perpetrated. Today, John Rigas, leader of the clan, and his dutiful CFO son Tim are behind bars and will remain so for many years.

Tip:

An incestuous family-dominated company with weak checks and balances may be acting entirely properly, but don’t count on it. Without independent checks and balances within the management ranks and on the board of directors, the risk for investors grows materially.

Watch for Senior Executives Who Push for Winning at All Costs.

HealthSouth CEO Richard Scrushy was renowned for pushing hard to meet or beat Wall Street estimates. Such a “win at all costs” culture can lead to aggressive accounting practices and, in some cases, fraudulent reporting. The Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) description of what went on behind closed doors at HealthSouth (HRC) reveals much about the culture of fear and intimidation:

If HRC’s actual results fell short of expectations,

Scrushy would tell HRC’s management to “fix it” by recording false earnings on HRC’s accounting records to make up the shortfall

. HRC’s senior accounting personnel then convened a meeting to “fix” the earnings shortfall. By 1997, the attendees referred to these meetings as “family meetings” and referred to themselves as “family members.”

At these meetings, HRC’s senior accounting personnel discussed what false accounting entries could be made and recorded to inflate reported earnings to match Wall Street analysts’ expectations.

[Italics added for emphasis.]

Be Skeptical of Boastful or Promotional Management.

Investors should be particularly careful when a management publicly boasts about its long consecutive streak of meeting or exceeding Wall Street’s expectations. Invariably, tough times or speed bumps emerge, and such a management may feel pressured to use accounting gimmicks and perhaps fraud to keep the streak alive, rather than announcing that its run of success has ended. This was certainly the case at Symbol Technologies and its 32-consecutivequarter “winning streak” that we discussed in the previous chapter. Companies engaged in many other blockbuster frauds had similar winning streaks, including supermarket giant Royal Ahold, auto parts maker Delphi Corporation, industrial conglomerate General Electric Company, and doughnut shop Krispy Kreme Doughnuts Inc. Royal Ahold, one of Europe’s largest frauds, enjoyed boasting about its streak on its earnings calls with investors:

This is

the thirteenth consecutive year

in which our net earnings have grown significantly. Ahold has always met or exceeded expectations during this 13-year period

and we intend to continue to do so.

[Italics added for emphasis.]

Warning Sign

: An extended streak of meeting or beating Wall Street expectations.

Boards Lacking Competence or Independence

It may be the best part-time job in the world. Sitting as an outside director on a corporate board brings prestige, perks, and a nice paycheck, with cash and noncash compensation often exceeding $200,000 per year.

While we know that this situation works out just fine for the lucky directors, often it is less clear whether investors receive the necessary and expected protection from these fiduciaries. Investors must evaluate board members on two levels:

(1)

do they belong on the board, and are they qualified for the committees on which they sit (e.g., audit or compensation), and

(2)

are they appropriately performing their duties to protect investors?

Inappropriate or Inadequately Prepared Board Members

Baseball fans surely remember longtime Los Angeles Dodgers manager and later corporate pitchman Tommy Lasorda. For sure, Tommy possessed talent on the baseball diamond and a personality and charisma that helped companies hawk their products. But as a board member for publicly traded Lone Star Steakhouse, Tommy may have been out of his league. While his seven decades in baseball are quite impressive, they probably did not provide him with strong financial analysis skills. Worse yet, former Heisman Award–winning running back and National Football League gridiron great (and later convicted felon) O. J. Simpson was assigned the duty of faithfully protecting investors’ interests by serving on the

audit committee

of Infinity Broadcasting in the 1990s. It’s difficult to imagine O. J. navigating his way through the intricacies of a Balance Sheet, let alone overseeing financial reporting and disclosure. Investors should ensure that outside board members have the essential skills and serve only on appropriate committees that suit their technical skills.

Failure to Challenge Management on Related-Party Transactions

Management at India’s information technology giant Satyam decided to make an acquisition in 2008 that needed board approval. The board met and acquiesced to management’s request, despite the fact that the CEO’s sons controlled the target company. Specifically, Satyam’s board approved the recommendation to invest $1.6 billion for 100 percent of Maytas Properties and 51 percent of Maytas Infrastructure. (The word

Maytas

is

Satyam

spelled backward— another clue for all you Sherlock Holmeses about the related-party nature of the deal.)

The board should have raised objections not only because of the related-party nature of the acquisition, but also because it made little sense. Any Satyam director should have been puzzled that the company was proposing to invest $1.6 billion in related-party real estate ventures at a time when its core business was under pressure and additional investments should have been poured into staving off the competition.

While the board agreed to the acquisition, it was aborted the next day after an investor uproar. Satyam’s CEO later told authorities that the deal was the last attempt to replace Satyam’s fictitious assets with real ones. A sign of a healthy and effective board is when a dissenting view overturns a management-driven consensus. That clearly did not happen at Satyam.

THE “SPORTS ILLUSTRATED JINX” EQUIVALENT FOR INVESTORS

The

Sports Illustrated

Jinx is a myth that states that individuals or teams that appear on the cover of

Sports Illustrated

magazine are tempting fate and will soon experience bad luck.

It seems that there are similar “indicators of doom” in the corporate world for accolades given to public companies and their executives. Exhibit A: Ernst & Young’s prestigious Entrepreneur of the Year award for 2007 was given to Satyam’s CEO, Ramalinga Raju (currently in jail). Exhibit B: Recipients of CFO magazine’s respected Excellence Awards include the 1998 winner, WorldCom’s Scott Sullivan (currently in jail); the 1999 winner, Enron’s Andrew Fastow (currently in jail); and the 2000 winner, Tyco’s Mark Swartz (currently in jail).

Failure to Challenge Management on Inappropriate Compensation Plans

Setting appropriate compensation falls squarely on the shoulders of outside directors, specifically those who serve on the compensation committee. Management may propose some outlandish scheme that inappropriately rewards executives far beyond reason. For example, in the mid-1990s, Computer Associates instituted a plan that later paid senior executives more than $1 billion in additional stock as a reward for keeping the stock price above a designated threshold for a 30-day period. Shockingly, the board went along with this excessive compensation plan.

Even more outrageous than the Computer Associates scheme was another compensation-related swindle that ripped off millions of investors in many different companies: the options backdating scandal. Hundreds of companies played this game, which was actually quite simple: the companies would grant stock options to executives and other employees, and “backdate” the options to reflect a price that was much lower than the one on the date the options were granted. As a result, employees received substantial unrecorded and undisclosed compensation in the form of bogus stock price gains. (We discuss the audacious option backdating scandal more completely in Chapter 7.)

When evaluating outside directors, investors must always ask whose interests they are favoring—management’s or investors’. Investors should also always question compensation plans that could easily be abused to improperly inflate executives’ wallets.

Need for Outside Directors to Avoid Inappropriate Actions That Lessen Their Independence

In addition to being engaged and challenging management over acquisition decisions, outside directors should refrain from any conflicting activities. For example, receiving loans or being permitted to purchase products from the company for less than the market price would be inappropriate. Moreover, even receiving remuneration for providing professional services to the company would cloud an outside director’s objectivity and appearance of independence.

Consider the relationship between Satyam and one of its independent directors, Professor Krishna Palepu of Harvard University. Palepu, a Satyam director since 2003, is considered a leading authority on corporate governance. Among the executive education programs he has taught is Audit Committees in a New Era of Governance. He also co-led Harvard’s Corporate Governance, Leadership, and Values initiative, launched in response to the recent wave of corporate scandals and governance failures.

Professor Palepu seemed to have had a lapse in good governance judgment. While serving on Satyam’s board, he also accepted “special remuneration” of nearly $200,000 in 2007 for providing professional services. While we are not questioning either the quality of the professor’s services or the fairness of the amount of remuneration received, it is hard to see how Palepu can be considered “independent.” We believe that independent directors should not be involved in such related-party arrangements, as they may impair their objectivity and the appearance of independence on important decisions.

In December 2008, Satyam’s board approved the related-party Maytas acquisition described earlier. Shortly thereafter, Palepu resigned as a director along with several other board members. Just nine days later, Satyam’s massive fraud was publicly revealed. Palepu stated that he learned about the fraud only after resigning from the board.

Auditor Lacking Objectivity and the Appearance of Independence

The independent auditor plays a crucial role in protecting investors from dishonest management and an indifferent and ineffective board of directors. Chaos would ensue if investors ever came to question the competence or integrity of the independent auditors. That is indeed exactly what happened in 2002 after Enron and WorldCom collapsed, Arthur Andersen disbanded, and the financial markets nosedived.

The auditor, however, can be either a friend or a foe of investors: a friend if the auditor is competent, independent, and fastidious in sniffing out problems; a foe if he is incompetent, lazy, or a rubber stamp for management. Sometimes the very high fees and close personal relationships built up over years lead to botched audits and big losses for investors. Here are the key factors to consider when evaluating in which camp the auditor actually falls—friend or foe.

Astronomical Fees Lead to a Conflicted Independent Auditor

Arthur Andersen, with its 85,000 employees in 84 countries, generated $9 billion in revenue in 2001, the year Enron collapsed and declared bankruptcy. Arthur Andersen had served as Enron’s sole auditor for 16 years, also performing internal audits and providing consulting services. According to Enron’s SEC filings, Arthur Andersen earned a whopping $52 million ($25 million for audit and $27 million for nonaudit services) in 2000.