Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine (28 page)

Read Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine Online

Authors: Julie Summers

Tags: #Mountains, #Mount (China and Nepal), #Description and Travel, #Nature, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Andrew, #Mountaineering, #Mountaineers, #Great Britain, #Ecosystems & Habitats, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Irvine, #Everest

With all arrangements in place Sandy told Lilian that the trek was due to start in earnest: ‘We are splitting into 2 parties from Kalimpong to Phari as there are huts that will accommodate 6 Sahibs; each a days march apart, between the two places; which will be comfier than tents.’ From Darjeeling to Kalimpong it would be ‘7000 ft down & 4000 ft up – quite a good start for the 1st days work’. To his father he wrote ‘I believe its Sunday today. Do tell Grandfather that we have a Medical Missionary as well as a Doctor with us. We start about 6 a.m. tomorrow morning.’

From the top of the pass for the first time the whole of the Everest system enters into close view. The fine highest mountains in the world are there in one grand coup d’oeil, west to east, Cho Oyu, Gyachungkang, Everest, Makalu and Kanchenjunga. Everest has pride of place in the centre immediately opposite, and is already displaying the great cloud pennon on its peak.

E. F. Norton, published 17 May 1924 in the

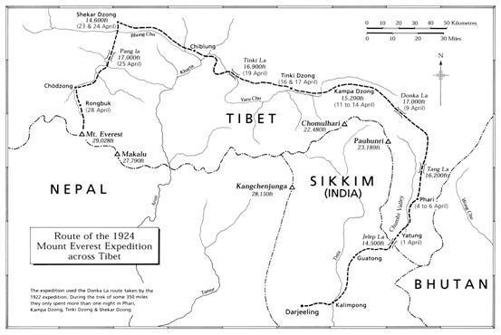

Times

In the 1920s the only way to get to Mount Everest was to trek from Darjeeling. The Nepalese border being closed to foreigners the only possible approach to the mountain was across the Tibetan plain, a march of some 350 miles. There were no proper roads so that the assistance of motorized vehicles was out of the question. Everything the expedition would need for the march in the way of equipment and, for the great part, food had to be carried by pack animal. Norton had laid on a few luxuries for the party such as tins of quail in foie gras and four cases of Montebello Champagne. The route took the expedition from Darjeeling to Kalimpong, a hill station and the last town encountered before entering Sikkim; through the steaming valleys of Sikkim to the Jelap La pass 14,500 feet which is the border between India and Tibet. From there the route leads down into the beautiful Chumbi Valley to Phari and thence onto the Tibetan plain, at a constant altitude of about 14,000 feet, with passes to be crossed at regular intervals, often three in a day at over 17,000 feet.

It was an enormous organizational feat and the experiences of the 1922 trek had lead them somewhat to modify the march, allowing for more time to cross the plain, but in the main the 1924 expedition took the same route as that of 1922. The expedition had some 3000 lb of food, tents and equipment which had to be transported on mules and ponies and the two transport officers Geoffrey Bruce and Shebbeare took charge of the luggage train. It was they who had to negotiate the frequent changes of transport required en route. General Bruce was concerned that he should get all his men to the foot of Everest in the best health possible. He described this responsibility as almost like dealing with ‘the crew of a university boat. They must be brought up to scratch without having suffered in any way from the arduous 300 mile journey across Tibet, or from degeneration in any form from the effects of a somewhat elevated route at a very early season of the year.’

With their porters employed and all their personal packing complete, the expedition was ready to leave Darjeeling on 26 March. They drove to 6th Mile Stone in Willis, or buses, from where they proceeded on foot to Tista Bridge. Sandy was absorbing the new sights and impressions that he encountered: ‘Coming down from Darjeeling’, he wrote in his diary that evening, ‘we saw some most beautiful butterflies and got some wonderful wafts of perfume on a very hot breeze. At one point … we came across a fine lizard sitting on a rock with its tail stuck straight up in the air.’ From Tista they proceeded on foot and pony to Kalimpong. Sandy was amused that his pony did not even start at the sound of a huge tree being felled above them: ‘a most impressive sight and a tremendous noise but curiously enough none of our ponies showed any sign of alarm.’

As far as I know Sandy had not had a great deal of experience of horse riding and it took him a while to get used to this mode of transport. There were several occasions when he was lucky to escape with nothing more serious than a scraped knee. As he was so tall and the ponies so small he found that the most expeditious way to stop them when they ran away with him was to put his feet onto the ground and, in effect, lift the animal into the air. This slightly unorthodox approach to horsemanship was evidently of amusement to him and the other expedition members and he related the story of such an incident in a letter to Geoffrey Milling: ‘All our ponies work on the rocket principle – that’s how they get along up the hills so well! They are tough little brutes, mine ran away with me up hill today, I had to put my feet down & lifted it off the ground to stop it.’ To his mother he was rather more honest about the discomforts he faced when riding. It would appear that, like his father, he had somewhat delicate insides. He wrote to Lilian, ‘the pony shakes my bladder up rather & tends to give me the old trouble but I think I ought to get hardened to that soon. For that reason I have been walking most of the way so far.’ In fact, for a variety of reasons, he ended up walking a good two thirds of the entire march on foot. He eventually got the hang of his pony and had some lovely rides with Mallory and Hazard during the trek.

Sandy was keen to give Lilian the richest picture he could of the scenery and the sights he was encountering. He wrote to her whenever he could find a moment, which was not often and frequently under less than ideal circumstances and sometimes had to break off mid-sentence: ‘- sorry if this writing has been rather shaky but my lad Tsutrum would insist that I had sweated in my stockings & they must be dried before the sun goes down so he has been taking off my shoes & stockings while I’ve been writing – well to continue …’ He went into great detail about all the arrangements for their overnight stays and was clearly impressed by the dak bungalows which were ‘very well looked after … this one has a lovely balcony with a superb view (if clear) & flower pots full of flowers all round & the whole place is most awfully clean’. He drew sketches in his diary and letters of many of the daks they stayed in, always making a note of the location of his own bedroom. His photography however he reserved for the scenery and the Tibetan people he met. He wrote to Lilian early on that he had kept a diary ‘so far which is pretty good work for me! Please keep my letters to fill out my diary when I get home.’ When he was in Spitsbergen he had kept a notebook and then written up his diary when he got back to Bergen after the expedition. He was clearly planning to do the same thing with the Everest expedition but had determined to write a somewhat fuller account on his return, hence the request to Lilian to keep his letters. His letters are fluent, descriptive and give a very clear picture of his state of mind as well as of the sights he saw and the experiences he enjoyed.

The expedition arrived in Kalimpong in the early afternoon and Sandy at once set to work on checking the oxygen stores, the stoves and the ladder bridge, all of which had arrived in advance of the party. Others were equally busy checking stores and adjusting to the thought of a five-week march where they normally would spend only a single night in one any location. Bruce had explained to the team that they would be split into two parties, walking one day apart, because the bungalows that they had arranged en route for Phari would not accommodate the whole expedition. After Phari they would all join up and continue together, sleeping in tents as they made their way over the Tibetan plateau. Sandy was in the second party, which as he had informed Lilian, comprised Mallory, Hingston, Shebbeare, Odell and Norton.

In keeping with the tradition he had established in 1922, General Bruce and the other members of the expedition visited Dr Graham’s Home in Kalimpong where he instructed Nepalese children in the tradition of the Boy Scouts. Bruce bore a message from Sir R. S. Baden-Powell and made an inspection of the ranks of children, who were beautifully turned out in their scout uniforms, complete with badges but bare feet. This was one of Bruce’s most pleasant duties as he reported with great pride and delight in his next Times dispatch: ‘A parade of the Boy Scouts and Girl Guides at the Kalimpong Homes was extremely attractive, and we were all immensely struck with their very remarkable appearance and the general enthusiasm and happiness of everyone. We had a charming meeting with them all and a great send-off.’ Duties thus dispensed the first party set off from Kalimpong and over the border into Sikkim. On the frontier they encountered a border guard who clearly tickled Bruce’s sense of humour: ‘When we had finished the necessary official documents, “Right hand salute” roared the guard at himself and duly saluted with the right hand; “left turn” he bellowed, and turned to the left; “quick march” he shrieked, and straightway took himself off. He was a Gurkha, and all Gurkhas love drilling themselves if they cannot get anyone else to drill them.’

After the first party left for Pedong the second party was obliged to spend a further day in Kalimpong. From the outset, whenever there was a break, Sandy would turn his attention to the oxygen apparatus and anything else that required his engineering skills and ingenuity. I have a sense that this first day of forced inactivity was something of a burden to him, for as Norton and others socialized with the MacDonalds, Perries and Waights, all local worthies, he hid himself away in his room with the excuse that he had things to fix, such as his watch. He was not yet feeling confident in the company and he preferred to keep away from events which would bring him into contact with yet more strangers. He wrote three long letters to friends in England, including his old rowing partner Geoffrey Milling, and Audrey Pim, Evelyn’s close friend from school.

Once he was on the march the next day Sandy’s spirits improved and the irritation of his broken wrist watch, which he’d only made worse the previous afternoon, paled. The road from Kalimpong to Pedong was one of outstanding scenery although the views were somewhat obscured that year owing to the mist which appeared to be as a direct result of an unduly dry season and thus a great number of forest fires. Kanchenjunga, the great mountain that dominates Sikkim and whose name means ‘Five Treasures of the Great Snows’ was only dimly visible through the mist. ‘It’s perfectly wonderful being able to go about in a bush shirt & shorts all day’, he wrote to Milling:

& get every damn thing done for you & be able to ride when ever you get tired of walking & through the most pricelessly wonderful glades in the jungle. We are under 6,000 ft here so the forest is pretty thick still; the only pity is that the visibility has not been good just lately – not for distances over 2 miles or so, otherwise the scenery would be wonderful. This is a remarkable place: it’s pitch dark now & it was bright sunlight when I started this letter – at least very nearly! … I say old Man Odell is just the same as ever! He longs to have you here the other members are getting quite fed up with our side illusions to you & Spits. They get such a lot of them.

But Odell was not the only person Sandy was talking to. He had gained confidence in Mallory’s presence and right from the beginning I sense that Sandy took considerable pride and delight in the fact that Mallory often chose to ride or walk with him. He invariably notes this in his diary and even mentions it on a couple of occasions in his letters home. I know from the photographs of the trek that he and Odell frequently road and walked together as well, but apart from a reference to Odell in this letter to Milling and the occasional reference to him in his diary, usually in connection with his health, the focus of his attention was Mallory. It is clear that if he were going to have any chance at getting himself onto a summit party Sandy would have consistently to impress Mallory and this he set out to do from the word go. If Odell had been a role model for him in Spitsbergen, how much greater a role model was Mallory on this expedition. With his knowledge of the mountain and his reputation as the best climber of his day and the man with the greatest chance to reach the summit it is hardly surprising that Sandy switched his allegiance. Odell was never going to be in contention as a lead climber in the present company, and Sandy realized this immediately. Sandy had set his sights no lower than the summit of Everest before he even left England and he was going to make sure that he got his chance at the top when the time came. Some ambition for a twenty-two year old. Whether or not this was hurtful to Odell is difficult to say but he did observe that Sandy ‘could not readily be drawn out to say much unless the environment was sympathetic. The high altitudes of Tibet perhaps a little emphasised this’. If there was a little friction it was never noticeable to the others and Odell and Sandy worked together for hours on end in respect of the oxygen apparatus and later, on the mountain, where they became a formidable relief team to climbers coming down from higher camps. Norton even referred to them as the well-known firm of ‘Odell and Irvine’.

One of the particular delights on the first few days of the march through Sikkim were the bathes Mallory, Odell and Sandy took in the rivers along the route. ‘I had 3 most delightful bathes yesterday & 2 today’, he wrote to Lilian, adding that unfortunately he had still not succeeded in acquiring the swim suit he had hoped to buy in Port Said, ‘though I manufactured quite a good one out of a belt & 2 handkerchiefs. It is a very bad thing indeed to be seen naked by any one in the country – just the opposite to what I expected.’ The water was deliciously warm and they even succeeded in finding a pool deep enough for a shallow dive. Later they found a spot where the river ran fast over rocks in small rapids and they spent a happy hour or so sliding over the warm rocks and small waterfalls, although Sandy did this once too often and scratched his bottom. Mallory was enjoying the bathes as much as Sandy. All the anxiety and impatience he had felt up to this point seemed to have dissipated. He was on the way to Everest in good company and he was quite relaxed. He wrote to Ruth extolling the virtues of the bathing and added: ‘We couldn’t be a nicer party – at least I hope the others would say the same; we go along our untroubled way in the happiest fashion.’ Everyone did indeed seem to be very happy. Shebbeare spent a great deal of time chasing and catching butterflies, Norton sketched and painted the scenery, Mallory read and planned with Norton the assault on the mountain, Odell was fully occupied with matters geological and Sandy was having a delightful time, watching and observing closely everything he saw in the villages they passed through, swimming whenever the occasion permitted and, in any spare time at the end of a march, fiddling with the oxygen apparatus. Despite his real enjoyment of the trek the apparatus was causing him some anxiety. He was appalled by how badly the cylinders leaked and how fragile they were. In the letter to Geoffrey Milling from Pedong he concluded: ‘The oxygen has been already boggled! They unfortunately haven’t taken my design but what they’ve sent is hopeless – breaks if you touch it – leaks & is ridiculously clumsy & heavy. Out of 90 cylinders 15 were empty & 24 badly leaked by the time they arrived at Calcutta even – Ye Gods! I broke one taking it out of its packing case!!’ The anguish over the oxygen apparatus is a recurring theme in Sandy’s diary and by the time he got to Base Camp he had completely lost his sense of humour. At this stage, however, he was still examining what Siebe Gorman had sent and discovering to his increasing disquiet the extent of the task that lay ahead of him.