Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine (40 page)

Read Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine Online

Authors: Julie Summers

Tags: #Mountains, #Mount (China and Nepal), #Description and Travel, #Nature, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Andrew, #Mountaineering, #Mountaineers, #Great Britain, #Ecosystems & Habitats, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Irvine, #Everest

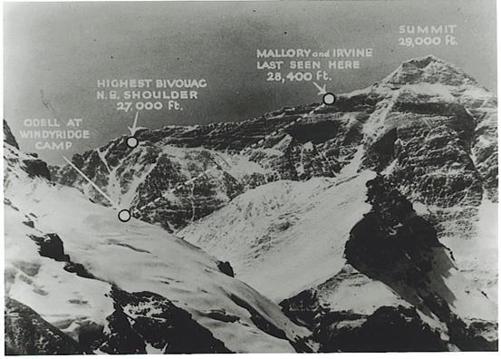

Moments after he saw them the cloud closed in and the whole vision vanished from his view. The diary entry goes on: ‘Had a little rock climbing at 26,000, at 2 on reaching tent at 27,000 waited more than an hour.’

Odell checked the tent and saw that Sandy had left it strewn with bits of oxygen apparatus. There were also a mixed assortment of spare clothes and some scraps of food and their sleeping bags. He was amused by the sight of the tent which reminded him of all the workshop tents Sandy had made wholly his own during the trek. ‘He loved to dwell amongst, nay, revelled in, pieces of apparatus and a litter of tools and was never happier than when up against some mechanical difficulty! And here to 27,000 feet he had been faithful to himself and carried his usual traits.’ He examined the tent for a note which might give some indication of the hour they left for the top or whether they had suffered any delay. There was nothing to be found. Meanwhile the weather had deteriorated. There was a blizzard blowing and he was concerned that the two men would have difficulty locating the tent under such conditions. He went out to whistle and holler with the idea of giving them direction. He climbed about 200 feet above the camp but the ferocity of the storm forced him to take refuge behind a rock from the driving sleet. In an endeavour to forget the cold he examined the rocks around him in case some point of geological interest could be found. Soon his accustomed enthusiasm for this pursuit waned and within an hour he turned back for Camp VI. He grasped that even if Mallory and Sandy were returning they would not be within hearing distance. As he reached camp the storm blew over and the upper mountain was bathed in sunshine, the snow which had fallen was evaporating rapidly. He waited for a time but, mindful of the fact that the camp was too small to house three men and also that Mallory had particularly requested him to return to the North Col, he set off back down the mountain. It had been Mallory’s intention, he believed, to get down to the North Col himself that night and even to Camp III if time and energy allowed as they were all aware of the possibility of the monsoon breaking at any moment. He placed the compass in a conspicuous position close to the tent door and, having partaken of a little meal, left ample provisions for the returning climbers, shut the tent up and set off back towards the North Col.

As Odell made his way down by the extreme crest of the north ridge he halted every now and again to scan the rocks above him for any sign of movement of the climbers. It was a hopeless task as they would be almost invisible against the rocks and slabs. Only if they’d been making their way over one of the patches of snow or being silhouetted on the crest of the north-east arête might he have caught a glimpse of them. He saw nothing. Arriving on a level with Camp V at about 6.15 p.m., about one and three quarter hours after he left VI he decided that he was making such good progress that he would head straight down the North Col to Camp IV. He noted that the upward time between those camps IV and V was generally about three and a half hours whereas his return time was closer to thirty five minutes. Descending at high altitudes, he concluded, was little more tiring than at any other moderate altitude.

Odell arrived at Camp IV at 6.45 p.m. where he was welcomed by Hazard who supplied him with large quantities of soup and tea. Together they scanned the mountain for any sight of light from a torch or distress flare but nothing was to be seen. It was a clear night with a moon that they hoped would help the returning climbers to find their camps. In his tent that night Odell reflected on the last two days. ‘And what a two days had it been – days replete with a gamut of impressions that neither the effects of high altitude, whatever this might be, nor the grim events of the two days that were to follow could efface from one’s memory.’ So great had his enjoyment been of the romantic, aesthetic and scientific experiences that he was able quite to put out of his mind the great hardship of climbing upwards at altitude. His thoughts, too, were focused on Mallory and Sandy, ‘that resolute pair who might at any instant appear returning with news of final conquest’.

The next morning they scanned the upper mountain and the two camps for any sign of life or movement but nothing was seen. At midday Odell decided that he would search both camps himself and before he left he arranged a code of blanket signals with Hazard so that they could communicate to some extent if necessary. This was a fixed arrangement of sleeping bags which would be laid out against the snow in the daylight. At night they would use a code of simple flash signals including, if required, the International Alpine Distress Signal. As Odell and his two porters left the North Col they encountered the evil cross-wind that had so taken the heart out of the first attempt of Mallory and Bruce ten days earlier. They reached Camp V in three and a quarter hours but the porters were faltering. Odell was disappointed to see that the Camp had not been touched or occupied. He had hardly expected to find Mallory and Sandy there as any movement would have been visible from Camp IV but how desperately did he wish that a trace of them would be found. ‘And now one’s sole hopes rested on Camp VI, though in the absence of any signal from here earlier in the day, the prospects could not but be black.’ In view of the lateness of the hour and the fact that his two porters were unwilling to go any higher, a search of Camp VI would have to be delayed until the following day. He passed a very uncomfortable night in the bitter cold, unable to sleep despite two sleeping bags and wearing every stitch of clothing he possessed. The wind threatened to uproot the tents and he had to go out from the safety of his tent to put more rocks on the guy ropes of the porters’ tent. As he lay in his tent Odell fiddled with the oxygen apparatus lying there and determined to take it up to Camp VI with him the next day.

As day dawned on 10 June the wind was as ferocious as ever and the two porters were even more miserable. Odell sent them back down to Camp IV and prepared himself for the upward slog to Camp VI. ‘Very bitter N. wind of great force all day’, he wrote in his diary, ‘climbed up slowly to W. of VI & finally reached tent.’ He was climbing using the same oxygen set he had used before and although he admitted it did allay the tiredness in his legs somewhat, he was not convinced that it gave him any real assistance. The wind forced him regularly to take shelter behind rocks all the way up the ridge and when he finally arrived in Camp VI he found the tent closed up, exactly as he had left it two days earlier. Bitterly disappointed he noted ‘no signs of M & I around’. He set out along the probable route that Sandy and Mallory had taken to make what search he could in the limited time available. His spirits were low. ‘This upper part of Everest must be indeed the remotest and least hospitable spot on earth, but at no time more emphatically and impressively so than when a gale races over its cruel face. And how and when more cruel could it ever seem than when balking one’s every step to find one’s friends?’ After two hours of struggling in the bitter wind, aware of the futility of his search, yet almost unable to turn his back on the mountain, he reluctantly gave up. At that moment, the awful truth dawned on him: his friends were nowhere to be seen and nowhere to be found. That sense of anguish is as strong today as it was in 1924. Whenever I read his account of that final search I sense the desperate feeling of fading hope as he comes to understand that the chances of finding them alive are all but gone. A lull in the wind allowed him to make the signal of sleeping bags in the snow as arranged with Hazard. A simple T-shape meant ‘No trace can be found, Given up hope, Awaiting orders’. Hazard received the signal 4000 feet below at the North Col but Odell was unable to read the answering signal in the poor light. What was there to read? He had sent down the mountain the worst piece of news conceivable and the only thought in his mind now was to get down safely in order to tell the others of his fruitless and hopeless search. Hazard relayed the message from Camp IV to the anxious climbers waiting at Camp III by laying out blankets in the form of a cross. Captain Noel spotted the sign through his telescope and when Geoffrey Bruce asked him what he could see, Noel was unable to reply. He simply passed the telescope over to him. ‘We each looked through the telescope,’ Noel recalled later, ‘and tried to make the signal different, but we couldn’t.’

The pre-arranged blanket signal that meant ‘No trace can be found, given up hope, awaiting orders’.

The pre-arranged blanket signal that meant ‘No trace can be found, given up hope, awaiting orders’.

Odell returned to the tent where he collected Mallory’s compass and Sandy’s modified oxygen apparatus. His last entry in his diary for that day reads: ‘Left some provisions in tent, closed it up & came down ridge in violent wind & didn’t call at V.’ It cannot have been an easy decision to leave Camp VI; it meant turning his back on Sandy and Mallory forever. As he turned to look at the summit above him he sensed it seemed to look down with cold indifference on him, ‘mere puny man, and howl derision in wind-gusts at my petition to yield up its secret – this mystery of my friends. What right had we to venture thus far into the hold presence of the Supreme Goddess, or, much more, sling at her our blasphemous challenges to “sting her very nose-tip”?’

And yet as he stood and gazed at the mountain, he was aware of the allure of its towering presence and he felt certain that ‘no mere mountaineer alone could but be fascinated, that he who approaches close must ever be led on … It seemed that my friends must have been thus enchanted also for why else would they tarry?’ Such a beguiling presence, such a deadly vision. The mountain was destined to keep its secret for over seventy years.

Finally he accepted that the other climbers in the camps below would be anxious for news of his discoveries, if there were any, and he knew in his heart of hearts that Sandy and Mallory could not have survived another night in the open above 27,000 feet.

His climb down in the teeth of the gale, struggling with the heavy oxygen apparatus, took all his effort and concentration. Frequently he had to stop in the lee of rocks to protect himself from the wind and check for symptoms of frostbite, but eventually he was spotted by Hazard who sent his porter out to welcome him with hot tea while Hazard brewed soup in camp. On his arrival Odell was pleased to find a note from Norton and to discover that he had anticipated his wishes by abandoning the search and not putting any further lives at risk, namely his own, seeing as the monsoon was expected to break at any moment.

Odell had spent a staggering eleven days above 23,000 feet and had climbed twice to above 27,000 feet without oxygen. It was one of the many extraordinary feats of strength demonstrated on the 1924 expedition and was all the more remarkable for the fact that he climbed entirely alone on both occasions to and from Camp VI, the place he described as the most inhospitable place on earth. His slow acclimatization was nevertheless thorough and complete, otherwise how could he ever have coped at those altitudes when others could not? Odell’s loyalty to the memory of his two friends has always deeply impressed me and it is a mark of the extraordinary man he was that he put himself through such torture in the vain hope that he might find them alive, or at least find out what had happened to them. Whenever I read his story of the last climb I always hold out a lingering hope that perhaps this time the story will be different, perhaps this time there will be a sign of them, that they don’t just disappear into the mists and into legend.

The following morning Odell, Hazard and the three porters gathered together all they could carry from the tents, including Mallory and Sandy’s personal belongings, Captain Noel’s cine-camera which Sandy had thought he might take on his summit attempt, left the tents standing and made their way down to Camp III for the last time. There they found Shebbeare and Hingston who were preparing to evacuate that camp, the others already on their way to Camp II and Base. While Odell and Hazard had been in support and searching from IV, other members of the expedition had been waiting anxiously at III. ‘During the next four days’, Norton wrote, ‘we were to pass through every successive stage of suspense and anxiety from high hope to hopelessness, and the memory of them is such that Camp III must remain to all of us the most hateful place in the world.’