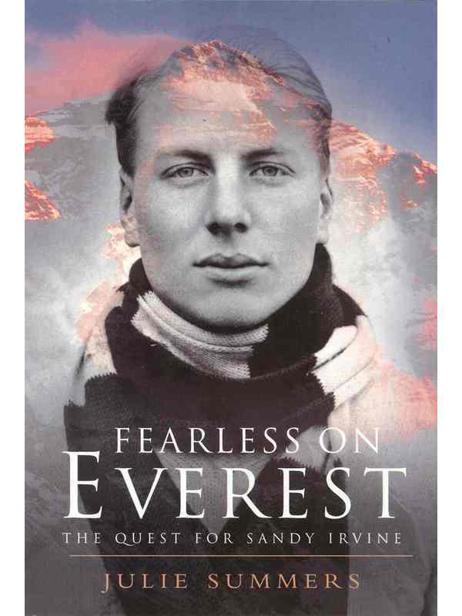

Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine

Read Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine Online

Authors: Julie Summers

Tags: #Mountains, #Mount (China and Nepal), #Description and Travel, #Nature, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Andrew, #Mountaineering, #Mountaineers, #Great Britain, #Ecosystems & Habitats, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Irvine, #Everest

Fearless on Everest

The Quest for Sandy Irvine

By Julie Summers

Sandy Irvine

Published by Iffley Press, Oxford, 2011

ISBN 9780956479518

First published in Great Britain in 2000 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

© 2000 Julie Summers

The moral right of Julie Summers to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act of 1988

All rights reserved.

Other titles by Julie Summers

The Colonel of Tamarkan, Philip Toosey and the Bridge on the River Kwai

(Simon & Schuster, London 2005)

Remembered: a history of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

(Merrell, London 2007)

Stranger in the House: women’s stories of men returning from the Second World War

(Simon & Schuster, London 2005)

Remembering Fromelles

(Commonwealth War Graves Commission, 2010)

www.juliesummers.co.uk

For Sandy

Bound for Darjeeling: The Tittle Tattle of Travel

Under the Finest Possible Auspices: The Trek Across Tibet

Trust in God and Keep Your Powder Dry

Brave heart at peace – youth’s splendour scarce begun

Far above earth encompassed by the sky.

Thy joy to mount, the goal was all but won.

God and the stars alone could see thee die.

Thou and thy comrades scaled the untrodden steep

Where none had ever ventured yet to climb

Wrapt in heroic dreams lie both asleep

Their souls still struggling past the bounds of time

Till God’s loud clarion rends the latest morn

Sleep on! We mourn not for ‘tis God knows best

Then rise to greet the glad eternal dawn

Flooding with flame the peaks of Everest

F. T. Prior, 1924

It seems to me nothing short of extraordinary that the interest in Sandy’s Irvine’s life has not diminished. When I wrote the original book in 2000 I thought that the ‘and Irvine’ of the Mallory and Irvine mystery would soon be consigned within the pages of a book to the dusty shelves of old shops and that interest would fade. How wrong can one be? In August 2011 an announcement hit the press of a new expedition to go and find his body, which an American amateur historian believes he has located somewhere high up on the mountain. I think that means that some six or even eight expeditions have been launched since Mallory’s frozen body was found on Mount Everest in 1999.

When asked, as I am every time this story reappears, whether I want Sandy’s body found I say no. Politely. Actually, I want to go on record as being more emphatic than that. I want to say loudly: ‘No, leave him alone. His life and death are part of the rich and enduring mystery of Mount Everest. He was a beautiful young man who died in the flush of youth. I have no desire to see images of his blackened, bird pecked corpse lying exposed on the mountain.’ Sensationalising his memory by such means would lessen the memory of his extraordinary life and his and Mallory’s final climb. Whether they made it to the summit or not is of little consequence. Their heroic achievement is something to respect and celebrate.

This book, the first full length biography I wrote, is a very personal portrait of Sandy Irvine. It is not without its flaws but I stand by it as an exploration of his brief but action-packed life.

Julie Summers

Oxford, October 2011

Everest Camp IV, 23,500 feet Monday 2 June 1924

air temperature 32° F, sun temperature 120° F

Sandy Irvine sat outside his tent, shoulders hunched, his hat pulled down over his ears, his scarf shielding his badly sunburned face. His skin had been severely blistered by the sun, and the wind on the North Col had so cracked his lips that drinking and eating had become painful and unpleasant. It was 10 a.m. and he had been up for five hours. There were no other climbers in camp. George Mallory and Geoffrey Bruce had set off two days earlier in an endeavour to climb the final 5500 feet to Everest’s summit. That morning at 6 a.m. Col. Edward Felix Norton and Howard Somervell had left to make their own attempt to scale the summit of the world’s highest mountain.

Sandy had cooked breakfast for them, a ‘very cold and disagreeable job’ he had confided in his diary. ‘Thank God my profession is not a cook!’. He had padded around in the snow, filling Thermos flasks with liquid, helping the climbers to check they had everything needed for two days above the North Col. He was left breathless by every exertion as he struggled to breathe in the oxygen-depleted air. As Norton and Somervell left he felt a great wave of frustration well up inside him. For six weeks he had lived with the belief that he would be making that final assault on Everest’s peak, but six days earlier, after a second retreat from the mountain, the plans had had to be radically revised.

In the absence of sufficient fit porters to carry loads above the North Col, Norton, expedition leader, had announced that there would not be an attempt on the summit using oxygen. The medical officer, Hingston, had examined all the men and declared Geoffrey Bruce the fittest and Sandy second, but with lack of mountaineering experience between them they could not make up a climbing party. Thus Mallory, as climbing leader, had been forced to make the decision that Sandy should be dropped in favour of Bruce, the fitter man. It was a bitter disappointment and one Sandy found hard to bear. Two days later he was fulfilling the role of support delegated to him and Noel Odell by Norton, the first time this task had been officially designated. ‘Feel very fit tonight,’ he had written, ‘I wish I was in the first party instead of a bloody reserve.’ As Norton and Somervell disappeared out of sight he saw the goal he had set himself, his own private challenge, slip from his grasp. There was no getting away from it, he was devastated.

Watching Karmi the cook fiddling with the primus stove he reflected on the last few weeks when he had graduated from youngest member on the expedition, ‘our experiment’ as General Charles Bruce had called him, to one of the four key climbers who, it was planned, would be spared a great deal of the hard work in a bid to keep them fit for their assault on the summit. So many things had conspired against them. With a great number of the porters badly affected by the altitude, there had been problems getting the higher camps stocked, but it was principally the weather that had defeated them. They had had to contend with subzero temperatures in the camps where in the 1922 expedition climbers and porters had basked in the sun and drunk fresh water from the little streams that ran down the glacier. This year everything was frozen solid. Twice they had been forced by atrocious weather to retreat to the lower camps. Still they were undaunted but the number of fit men had drastically diminished. Now two oxygen-less attempts were being made above him. All his hard work on that infernal apparatus had gone to waste, he rued, and he was left with the feeling that, for the very first time in his life, he was facing a major personal defeat.

Looking up again he was suddenly aware of movement above camp. Dorjay Pasang, one of Mallory’s climbing party, was on his way down. Suffering badly from the altitude he had been unable to go on beyond Camp V so Bruce had sent him back down with a note to say the others were intending to press on without him. Sandy reached for the field glasses and above Pasang he could clearly make out the figures of Mallory and Bruce. He was surprised. They were returning. He had certainly not expected to see them so soon. A hundred thoughts raced through his mind as he set two primus stoves going for the returning party. He grabbed a rope and set off to meet them above the Col.

‘George was very tired after a very windy night,’ he recorded in his diary that evening, ‘and Geoff had strained his heart. The porters had been unable to stand the wind and even Camp V was short of what they wanted in altitude.’

As he escorted the exhausted men back into camp he wondered whether Norton and Somervell would be faring better above them. He served out quantities of hot tea and soup, helped the climbers to take off their boots and to get inside their tents. He could sense that Bruce was depressed at the outcome, whereas Mallory seemed preoccupied and Sandy found it impossible to read his thoughts.

Just before retiring, Mallory turned to him: there would be another attempt. The two of them would climb with oxygen in three days time, providing the weather held. Sandy should go down to Camp III to prepare the oxygen apparatus and he would join him the following day after a rest. Sandy was delighted. He could scarcely believe that luck had turned again, this time in his favour. At that moment Odell, John Hazard and a small group of porters appeared from the lower camp and Sandy bounded over to Odell, his old friend and mentor, and told with evident boyish delight of the third attempt, the chance that he had little thought would now come his way. Odell recalled later that Sandy ‘though through youth without the same intensity of mountain spell that was upon Mallory, yet was every bit, if not more, obsessed to go “all out”’.