Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War & Reconstruction (78 page)

Read Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War & Reconstruction Online

Authors: Allen C. Guelzo

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #U.S.A., #v.5, #19th Century, #Political Science, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Military History, #American History, #History

Grant was also aware that, as a westerner, he was likely to be resented as an interloper by the Army of the Potomac. “The enlisted men thoroughly discussed Grant’s military capacity,” Frank Wilkeson remembered. “Magazines, illustrated papers, and newspapers, which contained accounts of his military achievements, were sent for, and eagerly and attentively read.” Most of the veterans were skeptical. “Old soldiers, who had seen many military reputations—reputations which had been made in subordinate commands or in distant regions occupied by inferior Confederate troops—melt before the battle-fire of the Army of Northern Virginia, and expose the incapacity of our generals, shrugged their shoulders carelessly. …” Wilkeson, who would be going into his first campaign under Grant, discovered that “Grant’s name aroused no enthusiasm. The Army of the Potomac had passed the enthusiastic stage. …”

14

Grant anticipated that skepticism, and he even toyed with the idea of bringing McClellan back into the Army of the Potomac at some level to rally the jaded army. He also wisely retained Meade as titular commander of the Army of the Potomac (even though Grant himself would travel with the army and give all the orders that mattered). In some cases, though, Grant was facing problems that political savvy had no way of addressing. This particular army was largely composed of three-year volunteers, and in the spring and summer of 1864, many of those enlistments were due to expire. The constant defeats the army had suffered had slowly undermined the veterans’ enthusiasm for another term of service, and only about half of the Army of the Potomac’s veterans would be persuaded to reenlist. Unless he could win some kind of smashing victory soon, Grant was liable to see a large part of the Army of the Potomac legally desert him.

15

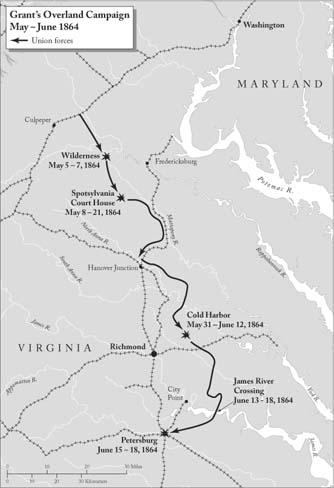

Staggering as these problems were, Grant managed to stay on his guard about letting the Army of the Potomac eat up all his attention and resources. He still believed that the really decisive blows that would win the war were going to have to land somewhere outside the old battlefields north of Richmond. To that end, Grant also provided for three other simultaneous offensives to begin in the West and below Richmond. Intended to help realize much of the original plan Grant had proposed to Halleck, those three offensives would depend largely on the men designated to lead them. First and foremost, there was William Tecumseh Sherman. Grant proposed to combine George Thomas and the Army of the Cumberland with Grant’s old Army of the Tennessee from the Vicksburg campaign and put them both under the command of Sherman. At the same time as Grant’s overland campaign would

open in Virginia, Sherman would advance south toward Atlanta with a view toward taking the city by the end of the summer.

In addition to Sherman, Grant also looked to Nathaniel Banks for help. Banks was supposed to finish his Red River expedition in time to launch a combined army-navy operation against Mobile in tandem with Grant and Sherman’s advances. With Sherman occupying the rebel Army of Tennessee, there would be little at hand to defend Mobile, and when the port fell into his hands, Banks could then move his men north through Alabama without serious opposition, wrecking Selma in his path, and then turn east and meet Sherman at Atlanta.

Lastly, Grant was looking for help from Major General Benjamin F. Butler, the Massachusetts politician who had outraged New Orleans and made the “contrabands” the beginning of a new Federal policy on slavery in 1861. Butler was to take command of two Federal army corps (about 33,000 men) and deposit them on the old James River peninsula, below Richmond. While Grant and the Army of the Potomac would clinch Lee in battle along the Rappahannock line, Butler and his men could slip past the thin Confederate defenses on the James and capture Richmond or at least cut Richmond’s rail communications with the rest of the South. Lincoln aptly summed up the plan in one phrase: “Those not skinning can hold a leg.”

16

Grant was less forthcoming about his reservations concerning the overland path across the Rapidan and the Rappahannock that Halleck and Lincoln insisted had to be taken en route to the climactic battle they wanted fought with Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. McClellan’s temptation to play at politics had tainted with halfheartedness the idea of using the navy’s command of the Chesapeake waterways to outflank the Confederates, push up the James River, and besiege Richmond. Surprisingly, that was exactly what Lee dreaded the most. “I considered the problem in every possible phase,” Lee told one of his division commanders in 1863, and unless he could carry the war onto Northern soil and make the North pay the price the South was paying, then taking a defensive stance would only end with him being pushed back into a siege of Richmond, and a siege—as the sieges of Sevastopol and Kars had shown during the Crimean War—had only one end in modern warfare, that of surrender. Nothing about the results of the Gettysburg campaign had changed Lee’s mind. “We must destroy this army of Grant’s before he gets to the James River,” Lee told Jubal Early. “If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.” This was also what Grant was convinced would be the inevitable outcome of affairs in the east, for the simple reason that armies had become too big to defeat in a single, cataclysmic battle, and too dependent on railroads and cities as

supply centers to survive in the field if those cities were locked up and captured. His intention, Grant wrote, was to “beat Lee’s army north of Richmond if possible.” But no amount of beating was liable to put the Army of Northern Virginia permanently out of commission; at least, none so far had done that. Instead, Grant mused, “after destroying his lines of communication north of the James River,” it would be better to “transfer the army to the south side and besiege Lee in Richmond or follow him south if he should retreat.”

17

Almost from the first, things began to go wrong with Grant’s big strategic picture. For one thing, Banks’s expedition up the Red River turned into an unpleasant little fiasco that tied up those forces (along with 10,000 of Sherman’s men who had been sent to reinforce him) until the end of May. By that time, Banks would have been a month late just starting for Mobile, and in fact, he never even got going at all, and spent the rest of the war in New Orleans. Sherman would have to take Atlanta himself, and without any helpful distractions at Mobile by Banks. Meanwhile, Butler and his “Army of the James” made a brave landing below Richmond on the James peninsula on May 5, 1864. Butler actually got within five miles of Richmond on May 11, only to be turned back by a desperate Confederate defense at Drewry’s Bluff on May 16. Butler withdrew back to the James River and entrenched himself in the Bermuda Hundred, a small area largely surrounded by a bend in the James. There the Confederates sealed off his small army, like a “bottle tightly corked.”

Grant’s biggest problem was presented by Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. Grant did not simply propose to throw himself at Lee, and like Hooker a year before, he chose not to try to force a crossing of the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg. Instead, the Army of the Potomac, with Meade and Grant, 3,500 wagons, 29,000 horses, 20,000 mules, and 120,000 men, again turned wide to the west, splashed across the Rapidan River on May 4, and plunged at once into the eerie gloom of the Wilderness. Despite the apparently irresistible juggernaut of his numbers, Grant had only about 65,000–70,000 veterans; the rest were unseasoned troops scraped from hither and yon (conscripts, replacements, the heavy artillery regiments of the Washington defenses; even Ambrose Burnside made a reappearance from Ohio with his old 9th Corps). Grant had to hope that he could move through the Wilderness fast enough to force Lee to fall back upon Richmond. “It was a good day’s work in such a country for so large an army with its artillery and fighting trains to march twenty miles, crossing a river on five bridges of its own building, without a single mishap, interruption or delay,” wrote Andrew A. Humphreys, Meade’s chief of staff. All the same, nightfall found the lead elements of the Army of the Potomac

no more than halfway along the narrow rutted roads of the Wilderness, and the army was forced to stop and wait for daylight.

18

This presented precisely the sort of opportunity Lee prayed for, since the tangled and unfamiliar terrain of the Wilderness would eliminate the Federal advantages in numbers and artillery and allow the Army of Northern Virginia an even chance in a fight. And that spring, Lee needed all the help the Virginia terrain could give. Three weeks before Grant crossed the Rapidan, Lee warned Jefferson Davis, “I cannot see how we can operate with our present supplies. … There is nothing to be had in this section for man or animals.” (No exaggeration, this: after three years of war, the countryside “seemed almost uninhabited and not even the bark of a dog or sound of a bird broke the dreary silence.”) Lee’s health was so poor that he admitted to his son Custis in April, “I feel a marked change in my strength… and am less competent for duty than ever.”

19

Moreover, Lee’s three corps commanders—James Longstreet (who had rejoined the Army of Northern Virginia with his corps after Bragg’s debacle at Missionary Ridge), A. P. Hill, and Richard Ewell—were all veteran officers with at least a full year of experience at corps command behind them. But each of them had failed Lee at Gettysburg. Even worse, Longstreet had performed ineffectively in Tennessee after Chickamauga, and quarreled so bitterly with his subordinates that two of them, LaFayette McLaws and Evander Law, resigned. Richard Ewell was “loved and admired” by his men, “but he was not always equal to his opportunities.” There would remain some question about how reliable their performance would be in the upcoming battles. Yet the morale of the ordinary soldier of the Army of Northern Virginia remained resilient. “The whole command is in fine health and excellent spirits and ready for the coming struggle confident of whipping Grant, and that badly. We all believe that this is the last year of the war.” John L. Runzer, of the 2nd Florida, resolved: “Whereas, we… believe, as we did, from the first, that the cause in which we are engaged… is just and right… Be it resolved, That we are determined never to give that cause up.”

20

The most immediate problem that Lee had to face, however, was concentrating his forces to meet Grant. In the interest of casting his net for supplies as far as he dared, Lee’s three army corps, numbering only about 70,000 men, were widely scattered along the south side of the Rappahannock. When Lee ordered them to rendezvous to face Grant, Richard Ewell’s corps, moving eastward on the Orange Turnpike through the Wilderness, collided with the vanguard of the Army of the Potomac’s 5th Corps, heading south on the one usable north-south road through the Wilderness, the Germanna Plank Road. A firefight erupted. Meade, anxious to get out of the Wilderness before the main body of Lee’s army arrived, tried to shoulder the Confederates aside, only to find the rebels in significantly greater numbers than he had planned for, and with a more aggressive spirit. “These lunatics were sweeping along to that appallingly unequal fight, cracking jokes, laughing,” wrote a Virginia artilleryman of his fellow Southerners, “and with not the least idea in the world of anything else but victory.”

21

Meade called up John Sedgwick’s 6th Corps to cover the 5th Corps’s southward-extended left flank. They, in turn, were overlapped by rebel infantry from Hill’s corps, coming up to meet them along the Orange Plank Road (a parallel to the Orange Turnpike) as twilight descended. That night, Meade moved the 9th Corps (Burnside’s) and the 2nd Corps (under Winfield Scott Hancock) around behind the firing lines so that, at five o’clock on the morning of May 5, Hancock and the 2nd Corps were in position to attack Hill. With a gigantic lurch forward, they smashed right over Hill’s rebels on the Plank Road. “Tell Meade we are driving them most beautifully,” Hancock exulted.

22

The exultation lasted only for an hour. Without any warning, the last of Lee’s infantry corps, under James Longstreet, arrived and knocked the overconfident Federals back to their starting point. It was now Lee’s turn to exult, and he was so jubilant at the appearance of Longstreet that he almost tried to lead one of Longstreet’s brigades personally (until a Texas sergeant grabbed the bridle of Lee’s horse and the protective shout went up, “General Lee to the rear!”). This confused melee of attacks and counterattacks through the dense underbrush and burning woods, little of it with any sense, produced a total of 18,000 casualties for the Army of the Potomac and another 10,000 or so for the Army of Northern Virginia. By midnight on the evening of May 6, both armies had lapsed into an uncomfortable quiet, too exhausted and confused to carry the fight on further.

23

Almost exactly one year before, Fighting Joe Hooker had found himself in the same situation and at the same location near the old Chancellorsville House, and he had elected to retreat. Much of the Army of the Potomac must have expected that Grant would make the same move, following the dingy and depressing pattern they had known for three years—attack, stall, withdraw across the Rappahannock. But Grant was not Hooker, and he was not like anything else the Army of the Potomac had ever seen. In the early morning hours of May 7, Grant arose, wrote out his orders, ate breakfast, and then moved out onto the road in the predawn darkness with his headquarters staff, past the burning wreck of the Wilderness and the long lines of Winfield S. Hancock’s 2nd Corps standing by the roadside—and headed

south

.