Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War & Reconstruction (37 page)

Read Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War & Reconstruction Online

Authors: Allen C. Guelzo

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #U.S.A., #v.5, #19th Century, #Political Science, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Military History, #American History, #History

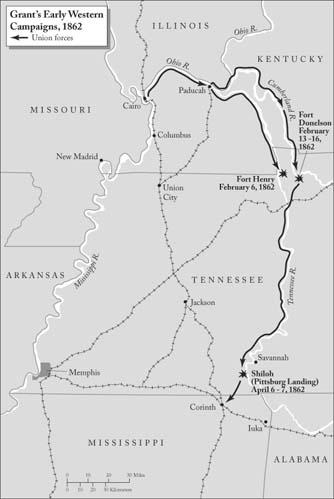

It went without saying, of course, that both the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers flowed through Halleck’s department rather than Buell’s, and that any such operation would be under Halleck’s command and not Buell’s. But Halleck had a point. Even Buell conceded that it might be a wise move to try to crack the Confederacy’s shell further to the west than he himself was operating. So, in January 1862, even while he was still haranguing Buell to move into eastern Tennessee, McClellan acceded to Halleck’s proposal to push up the two rivers into western Tennessee, with Nashville as the ultimate objective.

Halleck’s plan succeeded beyond anyone’s wildest dreams, and that was chiefly because he enjoyed two advantages that, it is safe to say, no one else in the world possessed. The first was a fleet of ironclad gunboats ideally designed for river warfare. Prior to the nineteenth century, and for almost as long as ships had been used as weapons of war, navies had been content to build their warships—and all their other ships—of wood, and relied on lofts of sail to move them. Even if the navies of Europe had seriously desired to plate their wooden ships with protective iron, the technology of iron making was too primitive and too expensive before the nineteenth

century to provide iron that would not shatter upon impact, while the inability of sail to move ships weighted down with iron armor would leave an ironclad warship almost dead in the water. In 1814, at about the same time that steam-powered riverboats first appeared on the Mississippi River system, the British navy began experimenting with steam propulsion in its warships, first in the form of paddlewheel steamers, and then in conjunction with new screw-type propellers. Then, in the 1820s, the French navy began developing explosive shells for use by its warships, so even the best-built wooden warship could be turned into a roaring holocaust with only one hit by a naval gun. With steam propulsion at last able to move heavier and heavier ships, and pressed with the urgent necessity of protecting their wooden warships from the fiery impact of explosive shell, both the French and the British navies began tinkering with the use of protective iron armor. The Crimean War of 1854–56, in which France and England were allied against Russia, gave the two navies the chance to try out their ideas under fire. They constructed five “floating batteries,” awkward and unseaworthy monstrosities that were little more than large wooden packing cases with sloping sides sheathed in wrought iron four and a half inches thick. Although these gunboats could only crawl along at the antediluvian speed of 4 knots, their iron sides proved invulnerable to anything the Russian artillery could do to them, and they were a tremendous success. “Their massive wrought-iron sides, huge round bows and stern, and, above all, their close rows of solid 68- and 84-pounder guns, show them at once to be antagonists under the attacks of which the heaviest granite bastions in the world would crumble down like contract brickwork.” When in 1859 the British launched the first full-size, seagoing armored warship,

Warrior

, the age of the ironclad had at last arrived.

15

The lessons taught by the “floating batteries” were not lost on American designers, and in August 1861 the War Department contracted with John B. Eads to build seven ironclad gunboats for use on the western rivers. Eads and his chief designer, Samuel Pook, built what amounted to a series of 512-ton floating batteries like those used in the Crimea, with flat bottoms, slanting armored sides of two and a half inches of iron plate, and an assortment of cannon. Known as “Pook’s Turtles,” the gunboats handled awkwardly, were badly overweight, and (since no one seems to have thought of who was going to operate them) had no crews. However, the naval officer detached to bring them into service, a stern anti-slavery Connecticut salt named Andrew Foote, managed to get the boats finished and launched, rounded up crews (with Halleck’s authorization), and otherwise provided Halleck with an armored naval flotilla. “Pook’s Turtles” were far from being great warships, but they were more than anything the Confederates had on the Tennessee or the Cumberland.

Still, nothing that Foote or the gunboats achieved along the rivers would have amounted to much if Halleck had not also possessed another, less obvious advantage, and that was an officer who could take command of the Union land forces, work in tandem with Foote, and win Halleck’s campaign for him. The name of that officer was Ulysses Simpson Grant.

No one in American history has ever looked less like a great general than Ulysses Grant. He was the sort of person one would have to stare at very intently just to be able to describe him, and there had been nothing in his life up to this point that in any way suggested that he was going to be a great general. He was born in Ohio in 1822 as Hiram Ulysses Grant, and his father managed to wangle him an appointment to West Point in 1839. (The congressman who made out the appointment papers somehow confused Grant’s name with the names of some of Grant’s relatives, and this turned him into Ulysses Simpson Grant.) No brilliant student, Grant graduated in 1843, twenty-first in a class of thirty-nine cadets, and although he was a talented horseman with a penchant for mathematics, he was shunted off as a lieutenant to the 4th U.S. Infantry. The Mexican War brought him his first action and first promotion to captain. But after the war, peacetime boredom and separation from his family drove him to alcohol, and in July 1854 he resigned from the army.

For the next seven years, Grant failed at nearly everything he tried, until his father finally gave him a job as a clerk in the family leather goods store in Galena, Illinois. Having been in the army most of his life, and with simple economic survival occupying all of his attention since leaving the army, Grant “had thought but little about politics,” he later recalled. Although he was (like Lincoln) “a Whig by education and a great admirer of Mr. Clay,” the disintegration of the Whigs left him with no one to vote for in 1856, and for a while he indulged a brief fling with the Know-Nothings. He soon enough grew weary of the Know-Nothings’ ethnic hate-mongering, but his fear that a Republican presidential victory in 1856 would trigger civil war threw him to the Democrats. He had not lived in Galena long enough to vote in the 1860 election, which (he reflected later) was just as well, for if he had voted, it would have been for Douglas.

16

When the war broke out, Grant unhesitatingly wrote to the War Department to try to get a commission in the regulars to fight secession. He never received a reply (the letter was found years later in “some out-of-the-way place” in the adjutant general’s office), but a month later the governor of Illinois appointed Grant colonel of the 21st Illinois Volunteers, and from then on, Grant went nowhere but up. In September a friend in Congress obtained a brigadier general’s commission for him, and in November he found himself under Halleck’s command in the Department of Missouri.

17

Grant and Halleck had both seen at virtually the same time the opportunity presented by the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. However, the Confederates in Kentucky also realized the vulnerability of the river lines and had constructed two forts at points on the rivers just below the Kentucky-Tennessee border, Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland. Both were in good position to bottle up the rivers pretty securely. Flag Officer Foote was confident that his gunboats could beat down the fire of the forts if Grant could bring along enough infantry to take the forts from their landward sides. So Halleck gave Grant 18,000 men, and on February 3, 1862, Grant put them onto an assortment of steamboats and transports, and along with Foote’s gunboats, entered the Ohio and then the Tennessee River for the turn up to Fort Henry. Built in 1861, Fort Henry was a small but powerful nut to crack: it mounted seventeen guns facing upriver, including a big 10-inch Columbiad, protected by fifteen-foot-wide earthen parapets. There were only a hundred men detailed to garrison Fort Henry, however, and heavy early spring rains put Fort Henry’s parade ground under two feet of Tennessee river overflow. Grant moved to the attack on the morning of February 6. Smothered by the fire of Foote’s four ironclad gunboats—

Carondolet, Cincinnati, St. Louis

, and

Essex

—the Confederates kept up a halfhearted fight at Fort Henry for three hours, and then abandoned it.

18

Almost any other Federal commander in 1862 would have sat down at once and begged alternately for reinforcements, more supplies, and a promotion. Grant now began to demonstrate to what degree he resembled no other Federal general in 1862 or any other year, for as soon as Fort Henry had surrendered, he sent one gunboat downriver to destroy the Memphis & Ohio railroad bridge over the Tennessee, and then he casually telegraphed Halleck that he was going to move over to Fort Donelson at once.

Fort Donelson was a considerably bigger target than Fort Henry: a twelve-foot-high earthen parapet enclosed fifteen acres of ground, plus a separate pair of “water batteries” at river’s edge with eight 32-pounder guns and another 10-inch Columbiad. Taken together, Donelson bristled with sixty-seven big guns and had a combined garrison of some 19,000 men, and the water batteries proved themselves quite capable of badly damaging Foote’s gunboats when they tried to duplicate their earlier success at Fort Henry. The Confederate command at Fort Donelson was divided unevenly between two incompetents, former secretary of war John B. Floyd and Gideon Pillow, and even more badly divided over its options. Floyd and Pillow threw away, by inaction, an opportunity to beat Grant piecemeal while his troops were still strung out on the roads between the two forts. They then threw away an

opportunity to evacuate Fort Donelson on February 15 when they punched an escape hole through Grant’s lines and then turned around and walked back to their entrenchments. The next day Fort Donelson finally surrendered to Grant. About 5,000 Confederates (including Floyd and Pillow) made off in the night, leaving 14,000 to fall into Union hands.

19

Little more than a single week’s campaigning had driven an ominous wedge into the upper South. It also made Grant a national hero, for when the last Confederate commander at Donelson, Simon Bolivar Buckner, sent out his white flag, suggesting that he and Grant negotiate for terms of surrender, Grant bluntly replied that he would consider “no terms at all except immediate and unconditional surrender.”

20

It was with a genuine sense of relief that the Northern public at last heard of a general who was concerned simply with winning.

When the news of the surrender of Forts Henry and Donelson struck Washington, the victory-starved capital went berserk with joy. Guns boomed all day, and in the Senate the frock-coated solons of the republic violated their own procedural rules by cheering and applauding like schoolboys. Grant suddenly found himself a man with a reputation for fighting, and on March 7 he was rewarded with a promotion to major general, while Foote won promotion to rear admiral when Congress created the new rank that summer. Grant’s aggressiveness was certainly a welcome departure from the attitude other Northern generals had brought to the battlefield, although this was certainly not because of what he had learned at West Point. Grant himself ruefully admitted that he “had never looked at a copy of tactics from the time of my graduation,” and even then, “my standing in that branch of studies had been near the foot of the class.” In this case, however, Grant’s ignorance only meant that he had less to unlearn and more readiness to adapt to the realities of his situation as a commander. “War is progressive,” Grant wrote in his

Memoirs

, and for an officer trained in an engineering-and-fortifications school and whose only war experience was the diminutive war in Mexico fifteen years before, Grant turned out to be a surprisingly progressive military thinker.

21

One way in which war had become very progressive, and very swiftly, was the use of the railroads and the telegraph. Electrical telegraphy was only seventeen years old

at the outbreak of the Civil War, and its first use had been to convey commercial news; the railroads were only slightly older, and they had been designed first for moving people, then freight. Both soon showed how easily they could be turned to military purposes, and especially for strategic communication and movement. Less than ten years after the first successful commercial railroad line opened, the Prussian army learned how to simplify deployment schedules by moving troops on rail lines. “Every new development of railways is a military advantage,” wrote the Prussian military reformer Helmuth von Moltke as early as 1843. “A few million [spent] on the completion of our railways is far more profitably employed than on our fortresses.”

Both the railroads and the telegraph were put to their first test for the British army in the Crimean War, when a newly formed Land Transport Corps built a track from the supply port of Balaklava to the siege lines around Sevastopol, accompanied by twenty miles of telegraph wire. Five years later Napoleon III took the railroads one step further and used them for troop transportation into northern Italy against the Austrians. French railroads moved 76,000 men in just ten days, and in the runup to the battles at Magenta and Solferino, it took some of Napoleon’s regiments only five days to reach their concentration point in northern Italy from Paris.

22