Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (54 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

6.

Ask whether the patient has had skeletal X-ray examinations. Note that X-rays are insensitive for bone loss, because a substantial reduction of bone mass must occur before changes will be visible on the X-rays.

7.

Take a careful drug history. Medications that cause osteoporosis include steroids, alcohol, heparin, thyroxine over-replacement, anticonvulsants (by affecting vitamin D metabolism), and cyclosporin.

8.

Enquire about a poor diet (a low-fat diet often limits calcium intake) or inadequate sunlight exposure if the patient is a nursing home resident, or has a history of renal disease or phenytoin use (all risk factors for osteomalacia) (

Tables 10.2

and

10.3

). Ask about the patient’s exercise history, as physical activity throughout life preserves bone mass. Cigarette smoking reduces skeletal mass.

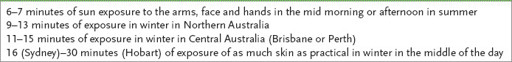

Table 10.2

Sun exposure and maintenance of normal Vitamin D levels in moderately fair-skinned people requires:

9.

Determine any risk factors for falls: a greater risk of falls increases the risk of fracture at any level of osteoporosis.

10.

Determine the social effect of the disease (e.g. immobility, pain, fear of falling).

11.

Have vitamin D levels been measured? Were they reduced?

12.

Ask about sun exposure (

Table 10.2

).

The examination

There are usually no signs of osteoporosis unless a recent fracture has occurred.

1.

Examine for bone tenderness and proximal weakness (osteomalacia). Look for bowing of the legs (rickets).

2.

Look for signs of thyroid disease and Cushing’s syndrome.

3.

Thoracic kyphosis is an important sign of vertebral fractures. The occiput to wall distance can be used to follow the condition.

4.

Assess weight and general nutritional status.

HINT

Vitamin D deficiency is increasingly commonly diagnosed in people of all ages.

Consider this in all patients with reduced bone density and especially in those with bone pain or muscle weakness. Risk factors include lack of exposure to sunlight (nursing home residents), fear of sunburn, dark skin and modest dress.

Investigations

1.

Bone densitometry using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) of the lumbar spine and/or proximal femur remains the test of choice for evaluation of bone mineral density (BMD; see

Table 10.4

).

Osteopenia

is used to refer to a bone mineral density between 1 and 2.5 standard deviations below peak bone mass;

osteoporosis

refers to a bone mineral density of more than 2.5 standard deviations below peak bone mass. The measurement is often given as a T score. This is the number of standard deviations by which the measured bone density falls below the average for a young normal person of the same sex. Thus, a T score of less than −2.5 defines osteoporosis.

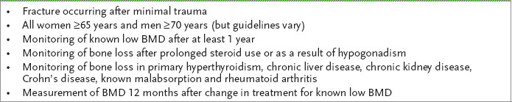

Table 10.4

Indications for bone mineral density (BMD) assay

2.

Review the serum calcium and alkaline phosphatase results. In osteoporosis, serum calcium and alkaline phosphatase levels should be normal. Alkaline phosphatase is usually elevated in all forms of osteomalacia. Check 25-OH vitamin D levels (not 1,25-OH vitamin D) if there are any risk factors for osteomalacia. If there is vitamin D deficiency, then serum 25-OH vitamin D levels are usually low (e.g. vitamin D malabsorption, chronic liver disease, lack of exposure to sunlight – especially common in nursing home patients).

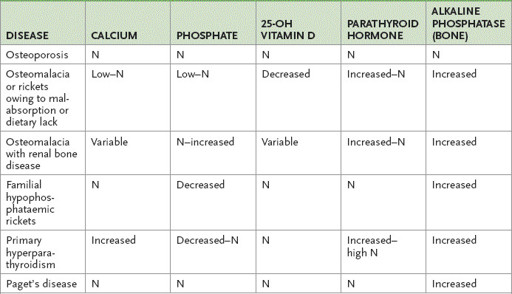

Assessment of calcium, parathyroid hormone and vitamin D levels will usually distinguish the most important causes of osteomalacia and allow specific diagnostic tests to be appropriately directed (

Table 10.5

). A sustained elevation of alkaline phosphatase should lead to consideration of osteomalacia, as well as Paget’s disease and metastatic malignancy to bone.

Table 10.5

Tests in bone disease

3.

A full blood count and ESR estimation should be ordered to look for evidence of myeloproliferative disease, and renal and liver function tests should be ordered to exclude renal or hepatic disease.

4.

Thyroid-stimulating hormone should be measured to rule out thyrotoxicosis.

5.

If osteoporosis is unexpectedly severe, then an EPG should be considered to rule out multiple myeloma. In men, a serum testosterone level is worthwhile.

6.

Ask to review any skeletal X-rays.

•

In osteoporosis of the spine, there is characteristic loss of trabecular bone in the vertebral body, including accentuation of the vertebral endplates. The vertebral trabeculae become more prominent with the loss of horizontal trabeculae. Also look for collapse, anterior wedging and the codfish deformity (from expansion of the intervertebral disc; see

Fig 10.1

).

FIGURE 10.1

X-ray of the lumbar spine showing loss of bone density (1), codfish deformity (2) and anterior wedging (3). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

•

In osteomalacia, X-rays may show some decrease in bone density with coarsening of trabeculae and blurring of the margins. A specific abnormality is Looser’s zones (pseudo fractures) in the long bone shafts; these are ribbon-like zones of rarefaction.

Other characteristic abnormalities may include a triangular (trefoil) pelvis and biconcave collapsed vertebrae. If there is secondary hyperparathyroidism present with osteomalacia, then bone cysts, erosion of the distal ends of the clavicles and subperiosteal resorption in the phalanges may be seen.

7.

In difficult cases, an iliac crest bone biopsy with double tetracycline labelling can help distinguish osteoporosis from osteomalacia.

8.

Consider undertaking tests for secondary causes of osteoporosis if the clinical picture suggests this may be helpful.

Treatment

Established osteoporosis is currently not reversible with medical therapy. Early intervention can prevent progression of osteoporosis and is of value. Secondary causes of osteoporosis should be identified and corrected if present.

1.

Calcium

. Because calcium absorption decreases with age, calcium therapy has a modest benefit in both early and late postmenopausal women. Consumption of 1200–1500 mg of calcium daily in adults over the age of 65 is advisable.

2.

Vitamin D supplementation

. Encourage sun exposure if that is possible. Moderate or severe vitamin D deficiency (serum 25-OH D <25 nmol/L) should be treated

with high-dose supplements of vitamin D of 3000–5000 IU/day for 6–12 weeks, and then 1000 IU/day from then on. Elderly women in nursing homes who have inadequate intake should receive supplementation of vitamin D 800 IU/day and calcium 1200 mg/day. This has been shown to reduce non-vertebral fracture risk.

3.

Generally recommend ceasing smoking, avoiding excess alcohol consumption

. Institute fall prevention measures and prescribe regular weight-bearing exercise. Consider a hip protector.

4.

Bisphosphonates (risendronate and alendronate)

. These drugs increase bone mineral density in postmenopausal women and have been shown to reduce the risk of fracture for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis by 50%. Patients unable to tolerate oral bisphosphonates can be given the drug as an infusion once every 3 months or, with some of the newer agents, once a year. The oral drugs can cause oesophageal ulceration that presents with odynophagia, usually within 1 to 2 months of commencing therapy. Osteonecrosis of the jaw is another serious possible side-effect, which is more likely to occur with intravenous formulations in the presence of previous dental infections. These drugs are now indicated for patients older than 70 who have a BMD T score of −3 or less and for those who have had a fracture after minimal trauma.

Strontium ranelate is an alternative drug for people who are unable to take bisphosphonates. Its effectiveness for preventing hip fractures has not been established, but there is evidence for its use in protecting against vertebral and rib fractures. It should be taken at bedtime at least 2 hours after eating.

5.

Oestrogen

. Hormone replacement therapy will prevent loss of cortical and trabecular bone in postmenopausal women. Therapy is probably more effective if started earlier in menopause as bone loss is most rapid then. Because oestrogen increases the risk of endometrial carcinoma, combination with progesterone is important unless a hysterectomy has been performed. A past history of endometrial cancer is a contraindication. There is an increased risk of breast cancer, as well as DVT and pulmonary embolism. Cardiovascular risk is also increased and hence its use in postmenopausal women has declined.

6.

Selective oestrogen receptor modulators

. Raloxifene, closely related to tamoxifen, reduces the risk of spine fractures. It increases the risk of DVT, but lowers the risk of breast cancer (and is not associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer). Tamoxifen is a mixed oestrogen receptor antagonist and agonist that prevents bone loss. It increases the risk of endometrial cancer.

7.

Parathyroid hormone peptide

. This drug is very effective for osteoporosis but very expensive.

8.

Calcitonin

. There have been inconsistent results with calcitonin and any effect is smaller than with other therapies. The drug can be given subcutaneously or intranasally. Administration can cause nausea, flushing and inflammation.

9.

Denosumab

, a humanised monoclonal antibody that reduces osteoclastogenesis by binding RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand), may have a role when other therapies fail.

10.

Men with osteoporosis

. In men who have osteoporosis and androgen deficiency, androgen replacement should be given unless there is a history of prostatic carcinoma. If there is secondary hypogonadism, human chorionic gonadotrophin or pulsatile gonadotrophin-releasing hormone may be worthwhile. Bisphosphonates and teriparatide (PTH) are efficacious in men; the role of raloxifene is not clear.