Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (53 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

FIGURE 9.10

X-ray of the hands showing marked calcinosis (arrows). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

R

aynaud’s phenomenon (resulting in loss of tissue pulp at the ends of the fingers)

(o)

E

sophageal involvement

S

clerodactyly (tightening of the skin on the fingers) (see

Fig 9.11

)

FIGURE 9.11

Sclerodactyly. W D James, T Berger, D Elston.

Andrews’ diseases of the skin: clinical dermatology

, 11th edn. Fig 8-25. Saunders, Elsevier, 2011, with permission.

T

elangiectasia

Progressive pulmonary fibrosis (ILD) is more common in patients with diffuse disease, but pulmonary hypertension is six times more common in patients with limited disease; it tends to occur late in the course of the disease. Patients with rapidly progressing dyspnoea are more likely to have pulmonary hypertension than ILD. These lung conditions are the main causes of mortality for scleroderma patients.

Localised scleroderma is called

morphea

. It presents as single or multiple plaques of skin induration.

The examination (see

Table 9.16

)

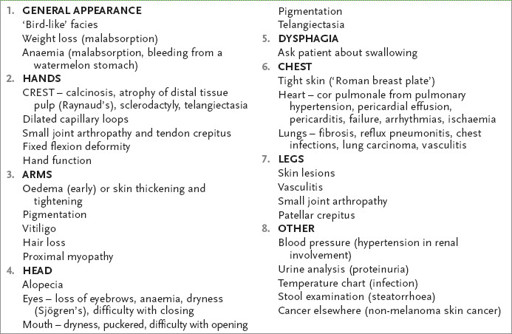

Table 9.16

Systemic sclerosis

1.

Make a general inspection for weight loss (owing to malabsorption or dysphagia).

2.

Look at the hands. Look for the signs of limited scleroderma. These include sclerodactyly (tightening of the skin of the fingers – see

Fig 9.11

) with extension up to the elbow, telangiectasia, finger tapering, pitting scars, signs of calcinosis (calcific deposits in subcutaneous tissue at the ends of the fingers) and the effects of Raynaud’s phenomenon (loss of tissue pulp at the ends of the fingers). Nail-fold capillaroscopy is useful, but few have the skill. The presence of dilated tortuous vessels (giant loops) almost always indicates an underlying connective tissue disorder of some sort. Assess hand function.

3.

Look at the arms for skin changes and assess proximal weakness (myositis).

4.

Examine the head. Note any alopecia. Look at the face for ‘salt-and-pepper’ pigmentation, loss of wrinkling, ‘bird-like’ or ‘mouse-like’ facies (because of puckering of the mouth) and telangiectasia. Check for any difficulty in closing the eyes, for dryness of the eyes (Sjögren’s syndrome) and pale conjunctivae (anaemia). Check for any difficulty opening the mouth wide and for dryness and puckering of the mouth.

5.

Look at the chest for the ‘Roman breast plate’ effect as a result of skin tightening.

6.

Examine the cardiovascular system for pericarditis, arrhythmias, cor pulmonale and cardiac failure (owing to myocardial fibrosis).

7.

Examine the respiratory system for interstitial lung disease, reflux pneumonitis, infection, lung carcinoma and vasculitis.

8.

Look for jaundice and xanthelasma (primary biliary cirrhosis occurs rarely with CREST). Scratch marks may be visible from pruritis.

9.

Look at the legs for vasculitis and ulceration.

10.

Take the blood pressure.

11.

Check the urine analysis and temperature charts.

Investigations

1.

The ESR may be raised. Anaemia may be present owing to chronic disease, iron deficiency (secondary to bleeding from oesophagitis), folate or vitamin B

12

deficiency (secondary to malabsorption), or a microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, which is usually associated with renal disease.

2.

Hypergammaglobulinaemia (particularly IgG) is present in 50% of cases. Rheumatoid factor is present in 25% and ANA is found in most cases. AntiScl-70 is positive in a minority with diffuse scleroderma. Anticentromere antibody is particularly associated with CREST (up to 70%) (see

Table 9.10

).

3.

Investigations for malabsorption and dysphagia may be necessary.

4.

Assess visceral involvement with chest X-ray films, gastroscopy or oesophageal manometry, depending on the clinical presentation.

5.

Regular screening for ILD and pulmonary hypertension should be routine:

a.

respiratory function tests, high-resolution CT of the chest for ILD

b.

echocardiography and, if pulmonary arterial hypertension is suspected, a right heart catheter and 6-minute walk test.

Treatment

This debilitating chronic disease will expose the patient to the need for recurrent investigations and adjustments to treatment. These matters need careful explanation from the outset. Prognosis is worse in men and those with renal or late-onset disease. Patients with skin and gut involvement, but without other organ disease, have the best prognosis.

1.

Symptomatic treatment includes avoiding vasospasm (by avoiding smoking, beta-blockers and cold weather). Aggressive treatment of reflux with proton pump inhibitors is important to prevent the formation of oesophageal strictures. Nifedipine,

phenoxybenzamine, prazosin or methyldopa may help Raynaud’s phenomenon. The prostacyclin analogue iloprost showed promise for Raynaud’s phenomenon in scleroderma. Morphea may respond to ultraviolet–A (UVA).

2.

Artificial tears are useful for dry eyes and NSAIDs may help with joint symptoms.

3.

Treat malabsorption (particularly bacterial overgrowth, with antibiotics).

4.

d-penicillamine (an immunosuppressant drug that also interferes with collagen cross-linking) may be helpful for skin disease and may improve survival. It has been usual to start treatment with a low dose. Randomised studies have shown no advantage of higher doses. The drug has a number of severe side-effects (see

Table 9.18

). Monthly full blood counts are usually recommended.

5.

Cyclophosphamide is used if there is lung involvement and may improve other complications of the disease, especially if used early. Treatment is usually given for 9 months.

6.

Pericarditis, inflammatory myopathy and early interstitial lung disease may respond to steroids.

7.

A number of drugs are now approved for the treatment of PAH in scleroderma patients (

Table 9.17

).

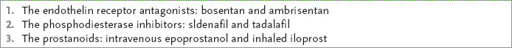

Table 9.17

Drugs approved for the treatment of PAH

8.

Aggressive treatment of hypertension to prevent renal failure is vital – ACE inhibitors are the drug class of choice. An ACE inhibitor is often given to patients even with abnormal renal function to prevent hypertensive renal crises. Dialysis is not contraindicated.

9.

Many other drugs have been tried for patients with scleroderma, including angiotensin receptor blockers, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin antagonists, topical nitrates and platelet inhibitors. There are no controlled trials showing that treatment can reverse the course of the disease.

HINT

Early diagnosis and treatment of ILD and PAH improves the prognosis; regular screening is most important.

CHAPTER 10

The endocrine long case

I would like to see the day when somebody would be appointed surgeon somewhere who had no hands, for the operative part is the least part of the work.

Harvey Cushing (1869–1939)

Osteoporosis (and osteomalacia)

Osteoporosis is increasingly encountered in the long-case examination. The patient is often a postmenopausal woman or is taking corticosteroids for an acute or chronic inflammatory illness. Osteoporosis will commonly form part of another medical problem. Osteoporotic fractures can affect 30% of postmenopausal women over their lifetime. Many older women have undergone screening bone densitometry and may be aware that they have asymptomatic osteoporosis. Patients who have had a hip fracture or who have evidence of an endocrine disorder, malabsorption, liver disease, Crohn’s disease or bone marrow disease, or who are taking certain medications, should have the possibility of osteoporosis considered while they are being evaluated (see

Table 10.1

).

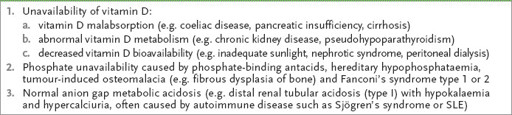

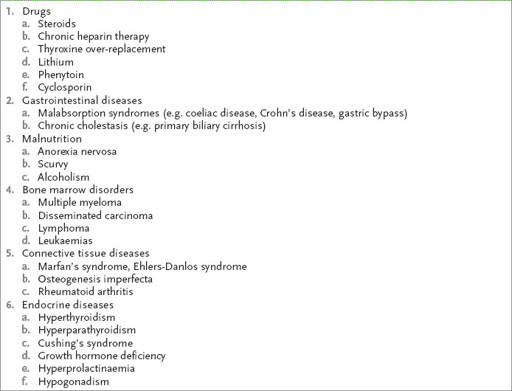

Table 10.1

Major secondary causes of osteoporosis

The history

1.

Ask about a history of fractures, particularly fractures of the wrist (risk increases from age 55), hip (risk increases from age 70), humerus and ribs, and vertebral compression fractures (especially T12), which may have occurred with minimal stress (risk increases from age 55). Acute back pain that subsides over weeks or months and then recurs may be caused by compression fractures.

2.

If the patient has had a hip fracture, ask about any secondary complications, including pulmonary thromboembolism and nosocomial infections.

3.

Ask about symptoms of bone pain, which may be diffuse, and proximal muscle weakness. These features may occur with osteomalacia (characterised by defective bone mineralisation in adults).

4.

Ask about risk factors for osteoporosis (

Table 10.1

). Determine the menstrual history and age of onset of menopause. Enquire about symptoms of thyroid excess or thyroid hormone replacement (thyroxine). Determine whether there are symptoms or a history of anaemia (e.g. coeliac disease).

5.

Ask about bone pain and proximal weakness (osteomalacia, usually due to vitamin D deficiency – then you must exclude malabsorption) (

Table 10.3

).

Table 10.3

Causes of osteomalacia