Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (84 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

The most likely problem is thyroid disease, but in the neck examination you should also consider the possibilities of superior vena caval obstruction, cervical lymphadenopathy, carotid aneurysm or bruit, JVP abnormalities and tracheal deviation.

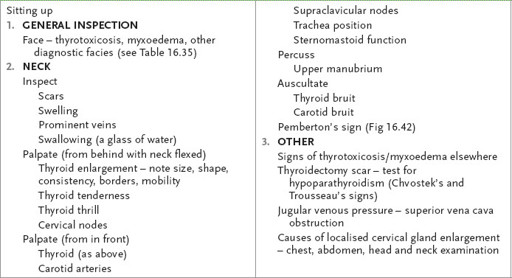

Table 16.25

Neck examination

1.

Take time first to look at the face for signs of thyrotoxicosis or myxoedema (see below).

2.

With the patient sitting up and the neck fully exposed, inspect for scars, swelling and prominent veins. Look at the front and the sides. Ask the patient to swallow a sip of water and look for thyroid enlargement. The thyroid moves up with swallowing.

3.

Palpate gently from behind, with the neck flexed, feeling for any thyroid mass (see

Table 16.26

). Use one hand to steady the gland and the other to feel. Note the shape, consistency and distribution of the thyroid enlargement. If a nodule is palpable, determine whether this is single or part of a multinodular goitre. Ask the patient whether the gland is tender (a clue to subacute thyroiditis) and note any hoarseness of the voice (which may be caused by recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy). Decide whether you can palpate the lower border of the gland (to exclude retrosternal extension) and whether there is a thrill. Feel for cervical lymphadenopathy

from behind. Palpate each carotid artery (absence possibly indicating malignant infiltration). Test the sternocleidomastoid function, as malignant disease may infiltrate this muscle. Finally, palpate the gland from in front and note the tracheal position.

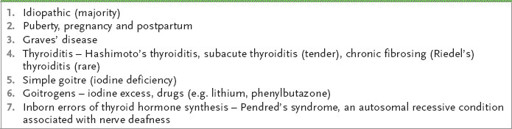

Table 16.26

Causes of a diffuse goitre (

Fig 16.43

)

4.

Percuss over the upper part of the manubrium from one side to the other, right across the bone, and note any change from resonant to dull (a sign of retrosternal extension).

5.

Auscultate over the thyroid gland for bruits (a sign of active thyrotoxicosis) and also over the carotid arteries. A systolic flow murmur is common when patients are thyrotoxic.

6.

Remember Pemberton’s sign. Ask the patient to lift her arms over her head. Look for suffusion of the face, elevation of the JVP and inspiratory stridor. Any retrosternal mass may cause these changes.

7.

If there is evidence of a goitre and obvious eye disease (indicating the presence of

thyrotoxicosis

; see

Table 16.27

), proceed to the face. Examine the eyes for exophthalmos by noting the presence of sclera below the cornea when the patient is looking straight ahead. Note lid retraction by looking for the presence of sclera above the cornea. Then test for lid lag by asking the patient to follow your finger descending at a moderate rate. Now examine the conjunctiva for chemosis.

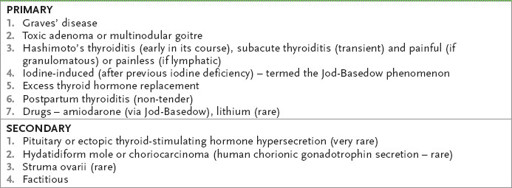

Table 16.27

Causes of thyrotoxicosis

Note:

The three components of Graves’ disease – viz. eye signs, hyperthyroidism with goitre and pretibial myxoedema – run independent courses.

8.

Test eye movements for ophthalmoplegia. The inferior oblique muscle power is lost first, then convergence is affected, followed by the other muscles in thyrotoxicosis. Examine the fundi because optic atrophy can occur late. Then look from behind, over the patient’s forehead, when she is looking forward, for proptosis.

9.

Examine the patient’s outstretched hands for tremor. It is worthwhile placing a sheet of paper over the dorsal aspects of the fingers. Look at the nails for onycholysis (Plummer’s nails) – distal separation of the nail from its bed – and thyroid acropachy (this looks like clubbing and is clubbing, but is not called clubbing!). Note any palmar erythema. Feel for warmth and sweating. Feel the radial pulse for sinus tachycardia, atrial fibrillation or a collapsing pulse.

10.

Test for proximal myopathy in the arms and tap the arm reflexes for briskness.

11.

If there is time, proceed to the legs and look for skin manifestations: pretibial myxoedema – bilateral firm, elevated dermal nodules and plaques that can be pink, brown or skin-coloured and that are caused by mucopolysaccharide accumulation – and vitiligo. Test for proximal myopathy and hyperreflexia in the legs.

12.

Ask to examine the chest for evidence of gynaecomastia (in men) and the heart for an ejection systolic murmur and signs of congestive cardiac failure.

13.

Although it is rarely of importance, there may also be mild splenomegaly and hepatomegaly on abdominal examination, as well as generalised lymphadenopathy.

14.

If a thyroidectomy scar is present, ask to look for the signs of hypocalcaemia (i.e. Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs). Chvostek’s sign may be present in normal patients. It is tested by tapping over the facial nerve 3–5 cm below and in front of the ear. The facial muscle twitches briefly in the presence of hypocalcaemia. Trousseau’s sign is tested by pumping up a sphygmomanometer cuff above systolic blood pressure and looking for

main d’accoucheur

(a strongly adducted thumb with fingers extended except at the MCP joints) that occurs within 2 minutes.

15.

If you suspect

hypothyroidism

(when goitre is unusual) (see

Table 16.28

), proceed as follows.

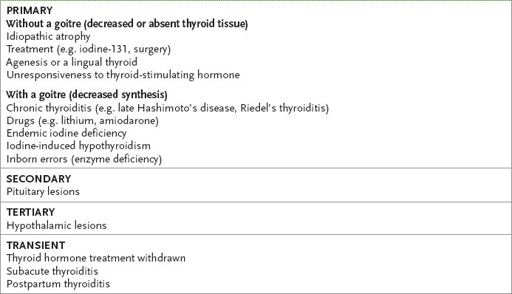

Table 16.28

Causes of hypothyroidism

a.

Examine the hands. Note peripheral cyanosis, swelling and dry, cold skin. Look at the palmar creases for anaemia (see

Table 16.29

). Feel the pulse for bradycardia and a small volume. Test for carpal tunnel syndrome. Ask the patient to flex both wrists for 30 seconds – paraesthesiae will often be precipitated in the affected hand if the carpal tunnel syndrome is present (Phalen’s wrist flexion test).

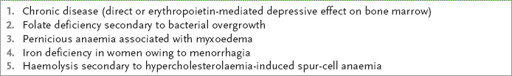

Table 16.29

Causes of anaemia in patients with hypothyroidism

b.

Test for delayed relaxation of the biceps jerk. Examine for proximal myopathy, which is rare.

c.

Proceed to the face. Note here any general swelling and periorbital oedema. Look for loss of the outer one-third of the eyebrows and periorbital xanthelasma. Note whether the skin is dry, fine and smooth. There may be signs of carotenaemia, alopecia or vitiligo. Look at the tongue, which may be swollen, then ask the patient to tell you her name and address and note any hoarseness or slowness of speech. Test for nerve deafness, which may be bilateral.

d.

Go to the legs next. Examine them neurologically, starting with the ankle jerks, noting particularly any evidence of slow relaxation, which is best seen with the patient kneeling on a chair. Then examine for peripheral neuropathy and look for other uncommon neurological abnormalities (see

Table 16.30

).

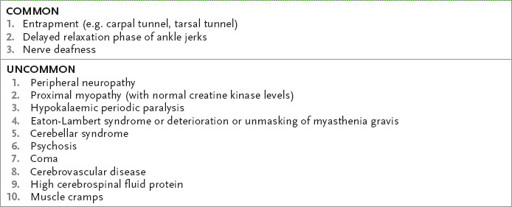

Table 16.30

Neurological associations of hypothyroidism

e.

Finally ask to examine the chest for pleural and pericardial effusions. There may be dry, rough ‘sandpaper-like’ skin over the chest.

Panhypopituitarism

‘This 35-year-old woman has lost her libido. Please assess her.’

Method

You cleverly note that this woman looks ‘panhypopituitary’ (see

Table 16.31

,

Fig 16.44

). Proceed as follows.

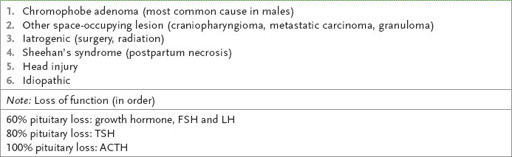

Table 16.31

Causes of panhypopituitarism