Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (87 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

*

Acute adrenal insufficiency may follow any stress in a patient with chronic hypoadrenalism or abrupt cessation of prolonged high-dose steroid therapy.

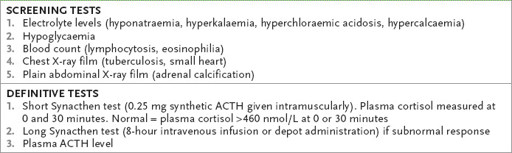

Table 16.40

Diagnosis of Addison’s disease

Diabetes mellitus

‘This 70-year-old woman has diabetes. Please examine her (or her legs or eyes).’

Method (see

Table 16.41

)

1.

General inspection may reveal a characteristic facial appearance (e.g. Cushing’s syndrome or acromegaly) or pigmentation (e.g. haemochromatosis), which will modify the examination approach. Otherwise, expose the patient’s legs. This is the only case in which there is an advantage in starting at the legs.

2.

Look for necrobiosis lipoidica over the shins (a central yellow scarred area with a surrounding red margin, if active, owing to atrophy of subcutaneous collagen – it is rare) (

Fig 16.50

), pigmented scars, skin atrophy, small rounded plaques with raised borders lying in a linear fashion over the shins (diabetic dermopathy), ulceration and infection. Look at the thigh for injection sites, fat atrophy (owing to the use of

impure insulin) or fat hypertrophy (owing to repeated injections into the same site, which leads to scarring and hypertrophy) and quadriceps wasting, from femoral nerve mononeuritis – called (inaccurately) diabetic amyotrophy.

FIGURE 16.50

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum. W D James et al.

Andrews’ diseases of the skin

, 11th edn. Fig 26.29. Elsevier, 2011, with permission.

3.

Inspect the feet and toes very carefully. Look for loss of hair, skin atrophy and blue, cool feet (small vessel vascular disease), ulcers and foot deformity. Feel all the peripheral pulses and note capillary return. Feel for pitting oedema. Auscultate over the femoral artery for bruits.

4.

Test proximal muscle power and test the reflexes. Assess for peripheral neuropathy, including dorsal column loss – called diabetic pseudotabes (p. 451). Charcot’s joints (see

Fig 16.51

) (owing to proprioceptive loss) may be present. (

Note:

Neuropathic joint disease: sensory loss (e.g. from diabetes, tabes dorsalis, amyloidosis, leprosy, meningomyelocele) allows repeated joint trauma, producing bony overgrowth, synovial effusion and joint distortion and instability.)

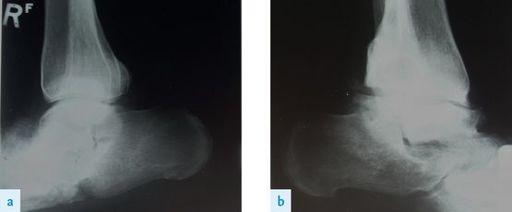

FIGURE 16.51

(a) and (b) Gross destructive changes in the ankle joints in a patient with diabetic neuropathy – Charcot’s joints. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

5.

Go to the upper limbs. Look at the nails for

Candida

infection. Feel the upper arm injection sites. Ask for the blood pressure and take the pulse lying and standing to detect autonomic neuropathy (see

Table 16.42

).

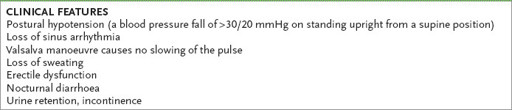

Table 16.42

Autonomic neuropathy

6.

Now examine the eyes for visual acuity. Remember, episodes of poor control cause lens abnormalities acutely. Look for Argyll Robertson pupils (which are rare). Remember, a diabetic third nerve palsy is usually pupil sparing – infarction affects the inner more than the outer fibres, whereas compressive lesions affect the outer fibres first and so involve the pupil early.

7.

Look in the fundi (see

Table 16.43

). While performing fundoscopy, also note the presence of cataracts and any new blood vessel formation over the iris (rubeosis).

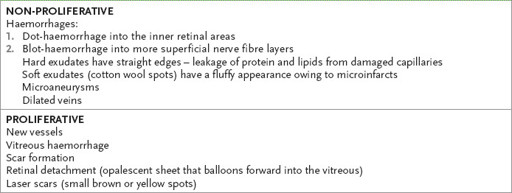

Table 16.43

Features of diabetic retinopathy (see

Fig 16.52

)

8.

Always test the III, IV and VI cranial nerves and remember that other cranial nerves may be affected. Periorbital and perinasal swelling with gangrene can occur with rhinocerebral mucormycosis, an opportunistic fungal infection.

9.

Look in the mouth for

Candida

and other infections.

10.

Look in the ears for infection (e.g. malignant otitis externa caused by

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

).

11.

Feel and auscultate the carotid arteries.

12.

Examine for hepatomegaly as a result of fatty infiltration and then ask for the results of urine analysis with respect to glucose and protein.

13.

There may be signs of chronic kidney disease with advanced diabetes.

14.

Ask whether you may weigh the patient.

Hirsutism

A diagnostic approach is summarised in

Table 16.44

.

The rheumatological system

In this section only the common joints that are encountered in the examination are discussed.

HINT

These rheumatological examinations are ripe for new more subtle stems related to assessment of function. The examiners may assume the diagnosis is obvious.

The hands

‘This 67-year-old woman has arthritis. Please examine her hands.’ (

Fig 16.54

)

FIGURE 16.54

Arthritic hands (rheumatoid arthritis).

Method (see

Table 16.45

)

When you are asked to examine the hands consider the possibilities of arthropathy, acromegaly, a peripheral nerve lesion, a myopathy or a neuropathy. If there is obvious joint disease, examine as follows.

Table 16.45

Hand examination

FIGURE 16.53

Porphyria cutanea tarda. P Yachimski, N Shah, R T Chung.

Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology

, 2007. 5(2):6, Fig 1.

Sitting up (hands on a pillow)

1.

GENERAL INSPECTION

Cushingoid

Weight

Iritis, scleritis, etc.

Obvious other joint disease

2.

LOOK

Dorsal aspect

Wrists

Skin – scars, redness, atrophy, rash, scleroderma (sclerodactyly) –

Swelling – distribution